Confused about the new deepfake ban ahead of Singapore’s GE? Here’s a breakdown.

The Singapore government just passed a new law banning deepfakes in light of the upcoming General Elections, here's all you need to know.

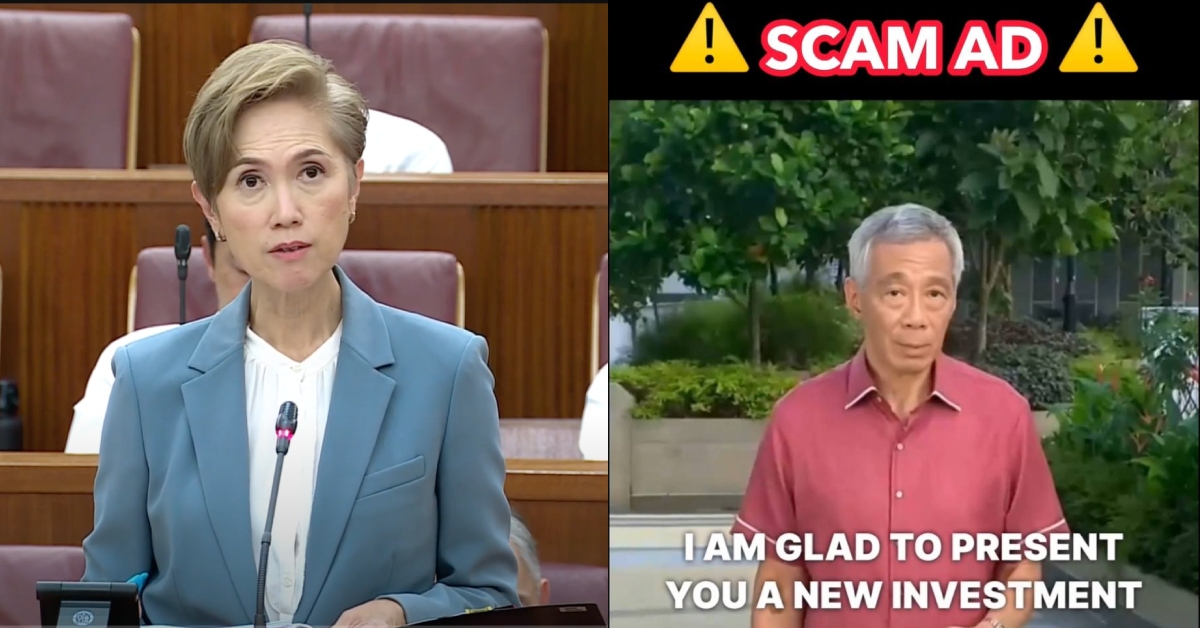

The Singapore government has introduced a new law in a bid to prevent the dissemination of false digital depictions of election candidates, ensuring the truthfulness of their representation and protecting the integrity of the country’s elections.

The new law comes ahead of Singapore’s upcoming general election, which must be held by November 2025.

Digital Development and Information Minister Josephine Teo announced the legislation, known as the Elections (Integrity of Online Advertising) (Amendment) Bill, or ELIONA, which was passed yesterday (October 15) in parliament.

According to an article by The Business Times, Minister Teo stated that the law amends Singapore’s election legislation and will address “the most harmful types” of elections-related content, which misleads or deceives through a “realistic enough” false representation of a candidate’s speech or actions.

There are different caveats and conditions to the new law; here’s a breakdown:

What type of content will be banned?

Content will be banned if it meets four criteria:

Being or including online election advertising Digitally altered Depicts an untrue representation Appears realistic enough for some members of the public to believe itThis includes content altered with artificial intelligence (AI), as well as “more traditional” methods like Photoshop, dubbing, and splicing.

Minister Teo referenced a recent study by Verian in her speech, which showed that more than six in 10 Singaporeans are concerned about deepfakes influencing the next election.

What will not be banned?

On the other hand, ELIONA will not apply to the following:

Unrealistic characters Cartoons Beauty filters Memes Satire Campaign posters that are unrealisticHowever, Minister Teo clarified that labelling manipulated content won’t automatically exempt it from prohibition, as labels can be removed or unnoticed, and there are ways to remove it before recirculation.

Whether the content favours a candidate or not is irrelevant. In the case of this legislation, publication includes boosting, sharing, and reposting. However, the law will provide a defence for those who inadvertently commit the offence.

Sharing content privately and in closed groups is not covered under the law, but dissemination of such content in large public chat groups on platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram is subject to it. In such cases, the government will assess if action should be taken.

The prohibition does not apply to news published by authorised news agencies to facilitate fair reporting.

Regarding realism, Minister Teo stated that it will be objectively evaluated, though there are no strict guidelines. However, the match to candidates’ features and mannerisms, as well as the use of actual persons, events and places, could be considered.

She also acknowledged that individual perception can vary, considering differences in individual experiences, beliefs, and cognitive biases.

“In this regard, the law will apply so long as there are some members of the public who would reasonably believe that the candidate did say or do what was depicted.”

What are the consequences?

ELIONA will give the returning officer authority to issue corrective orders to remove or disable access to prohibited content during the election period, which will apply during the election period—from the moment the Writ of Election is issued to the close of the polls on Polling Day.

These safeguards will only apply to prospective candidates who have paid their election deposit and consented to publicising their candidacy.

Some MPs expressed concerns about the law’s timing and scope. People’s Action Party MP Yip Hon Weng and Workers’ Party MP He Ting Ru raised concerns that deceptive information can sway public opinion before the official election period.

While Minister Teo acknowledged their concerns, she explained that the law can only take effect after the Writ of Election is issued and Polling Day is revealed.

To address this, a Code of Practice is currently being developed to enforce safeguards for specified social media services outside the election period and is expected to be finalised in 2025.

When reviewing flagged content, the government will rely on the candidates’ declarations, as they can quickly identify if their depictions were false.

However, penalties will apply for false declarations to prevent misuse of the law. An independent technical assessment will also be conducted to verify manipulated content.

Other candidates and the public can report content as well. In such cases, the affected candidate will be asked for a declaration, but the returning officer may act even without the candidate’s declaration should they have objective proof of a violation.

A dedicated team will monitor and act quickly on prohibited content during the election period. The Elections Department will provide details on how the public will be informed of corrective actions “in due course”. Those who believe a corrective order is wrongful can appeal.

If a provider of social media services does not comply with a corrective direction, it can be fined up to S$1 million, in line with similar legislation. All others, including individuals, are subject to a fine not exceeding S$1,000, a jail term not exceeding 12 months, or both.

Read our other articles on Singapore’s government technology here. Read other articles we’ve written on Singapore’s current affairs here.Featured Image Credit: Ministry of Digital Development and Information of Singapore (MDDI) via YouTube/ Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong via Facebook

JaneWalter

JaneWalter