Cooking at the end of the world in Final Fantasy XIV

How Endwalker explores the relationship between video game food and tech culture Continue reading…

This story contains spoilers for Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker.

The end of Eorzea is nigh, and I’m running around looking for ingredients for a superbread that will sustain its entire population on a space voyage to find a new planet. Panaloaf isn’t just any old type of bread, but a meticulously designed science experiment meant purely as a vessel for nutrition; since it’s a disaster ration, it can only be made using resources available on our spacecraft, which just so happens to be the moon. It goes without saying that panaloaf tastes like utter shit, and the thought of eating it for a day, much less a year or even a decade, is absolute hell.

This isn’t a Silicon Valley doomsday scenario, but the Culinarian questline in Final Fantasy XIV: Endwalker set in the isolated city of Old Sharlayan. (Culinarian is a non-combat crafting profession that revolves around cooking.) Sharlayans have quite a bit in common with the techbro stereotype: a thirst for knowledge; a critical disconnect from the majority of social, cultural, and economic realities; and a disdain for the humanities. And while I’ve played plenty of games in speculative settings where worldbuilding relies on miserable food, the Culinarian’s unassuming journey opens a door into a rather unexplored realm: the connection between video game culture and startup attitudes toward eating, in an age fixated on technological progress. It’s also an age defined by climate crisis. For some, the anthropocene isn’t coming; we’re already in it.

Faced with the coming apocalypse, the Culinarian must help nutrition student Debroye with the seemingly impossible task of making panaloaf edible. It’s an extreme version of Sharlayan’s most infamous food — the much-maligned Archon Bread, a dry, ashy, flavorless loaf that busy students use to stave off starvation. Thankfully, not all Sharlayans are like this. Debroye is a passionate foodie who works at the only restaurant in Old Sharlayan that cooks proper meals.

Panaloaf is the brainchild of Debroye’s supervising professor Galveroche, who follows the Sharlayan belief that good food is a “wasteful abomination.” As Debroye toils to make panaloaf more appetizing, it becomes clear that this isn’t just about practical disaster rations. “Can you imagine… if we were forced to live on panaloaf alone?” she says. “People would survive, but gods, would they wish they hadn’t.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23277261/ffxiv_12192021_231454_145.png)

It is impossible to play through this questline without thinking of real-life meal substitutes like Soylent, MealSquares, and Huel. But social commentary wasn’t Square Enix’s intent — it all started as a simple premise. “The first thing that came to mind was a story revolving around ‘making unappetizing food taste delicious,’” explains quest designer Yuki Kimura, who read meal substitute books, studies on the nutritional value of bread, and tried BASE BREAD, which entered the Japanese market in 2020 as the “world’s first nutritionally balanced” bread. “Those who perceive food as ‘fuel’ are simply so immersed in… what they are doing that they want to save the time it would take for them to have a meal,” says Kimura. “In games like Fallout, meals are tied directly to survival, and you end up eating anything that functions as ‘fuel’ for the character, so that might drive that notion further. I do see games depicting hunger as a sort of fuel gauge sometimes.”

When it comes to dystopian game food, the modern RPG player is spoilt for choice. Quarians in Mass Effect favor a tasteless nutrient paste, EVE Online has popular “protein delicacies” manufactured by megacorporations, Fallout is a revolving door of drugs and questionable packaged snacks, Deus Ex has textured soy food, and Half-Life has “water flavor” desiccated sustenance bars. Most of these are tongue-in-cheek worldbuilding elements that answer the most basic questions posed by speculative fiction: how and what will we eat in a crisis or in a situation where resources are scarce?

I initially operated on the idea that video games had an impact on the fairly recent tech-driven idea of easy meal substitutes, but this symbiotic relationship goes back over decades. “When I read about the proto-hackers and gamers of the 1960s they’re recognizably similar in their attitudes to food and their bodies,” says Austin Grossman, who co-wrote the iconic cyberpunk game Deus Ex. “That same cultivated indifference to the body…but blissful absorption in the machine — that interrupting it would trigger such a spike [of] anxiety — that you want to arrange to eat with the minimum possible disruption,” he says. “You want to feel like a machine yourself — treating food as fuel or battery charge.” He’s referring to early programmer behavior at MIT as told by computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum who created the ELIZA chatbot in 1964. “More or less the same scene I encountered when I first met game developers in the 1990s, with a little more gender diversity,” Grossman adds.

Grossman also believes it’s a reaction against “decision fatigue,” like how Steve Jobs’ constant black turtleneck meant that he had one less thing to think about every day. It isn’t just that we’re expected to function like machines in work, but in a gaming environment — especially in MMORPGs that have competitive raiding communities and, of course, esports — we’re also meant to learn and perfect game mechanics and choreographed combat sequences down to the millisecond. In this context, who has time to think about what they’re wearing or what they’re going to eat for dinner? The concept of eating becomes as stupidly simple as the pixelated MREs you might pick up in Half-Life. You gotta put something in your body, you gotta do it seamlessly and quickly, or else you’re gonna die. The body, with all its inconsistencies and material needs, is a source of annoyance.

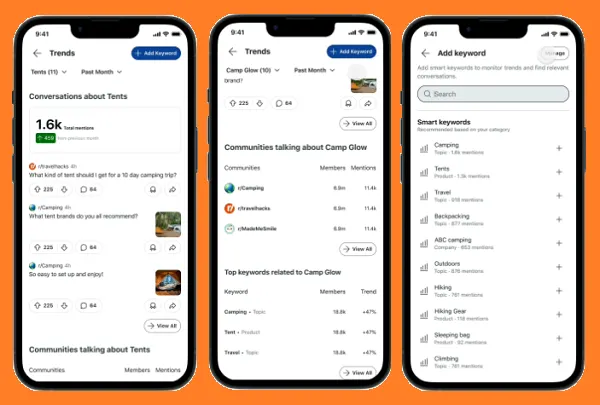

With a little marketing flair, today, we have RBG-colored “gamer fuel” in the form of energy drinks and convenient snacks that don’t get in the way, which includes gamer nut butter, a product designed to mimic energy gel and be eaten right off the spoon. This isn’t anywhere close to a necessity, but it’s a way for brands to create a sense of thematic unity with gamers’ mindsets when they’re in the proverbial zone. When Soylent was created back in 2013, founder Rob Rhinehart claimed that food is a waste of money and time (and doubled down again in 2020). But over time, despite its dystopian origins, it had harried students and busy coders buying bottles and powders in bulk. Today, it’s trying to rebrand itself as a nutrition company aimed at people with medical conditions who have difficulty putting on healthy weight. To that end, it had to work on improving its taste, while also realizing that people were drawn to the idea of “healthy alternatives” despite not fully knowing what that means.

Soylent, largely considered the OG of startup food tech, isn’t alone in this marketing pivot. Romeo Stevens, the formulator of MealSquares (“a nutritionally complete meal made from whole foods”), explained that the company “went through over 100 prototypes and consulted with people who handle total dietary replacement for medical purposes,” but declined to respond to further emails. Like its meal substitute brethren, MealSquares — what appears to be slightly over-engineered energy bars — touts itself as a product for busy people who don’t have time to think about the finer details of nutrition.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23277267/ffxiv_12192021_231609_521.png)

It’s a little depressing that if our ability to survive the world hinged upon eating one thing for an indefinite period of time, certain techbros would have an advantage over people who value taste and variety as oft-overlooked factors in mental and emotional health. It is Quite A Choice to claim that food sucks so we should all drink pre-mixed powder juice instead; it’s such a perplexing perspective that it’s mostly relegated to dystopian or mega-crisis settings, and firing up a game is often the closest you can get to touching the edge of that nightmare without actually subscribing to monthly deliveries of Huel.

What FFXIV’s Culinarian quest does is give us a well-crafted glimpse of the emotional and psychological journey to reach that nightmare, albeit with an unsurprisingly sentimental conclusion. Cast out by Galveroche, a furious Debroye decides to make her own version of panaloaf, which she names Mervynbread. The ruling body of Sharlayan, the Forum, will choose between panaloaf and Mervynbread as the official ration of the exodus. Naturally, while Galveroche’s panaloaf meets the Forum’s baseline requirements, nobody can imagine being forced to eat it for an indefinite period of time. Mervynbread, with its “frivolous” concessions to taste and aroma, isn’t just about giving people necessary calories and nutrients, but reminding them of the possibilities of pleasure and a future worth living.

Busy people like Sharlayans, bless their hearts, would probably love Soylent. But the rest of Eorzea would find it difficult, if not impossible, to sustain themselves on what FFXIV essentially describes as tasteless ash in your mouth. In many ways, what Debroye is doing with Mervynbread is a form of sensory marketing, which is essentially how a brand or business uses sensory stimuli to create appeal. It is the art of selling us what we want, without us knowing it — like walking past Cinnabon and being assailed by the scent of piping hot cinnamon rolls or Soylent reworking its flavors and platform to focus on nutrition.

As previous Culinarian quests in FFXIV have shown, food is ultimately a great emotional driver of mood and perspective. Perhaps it’s the game’s unique position on the outskirts of hard science — the franchise has always had a playful approach to marrying magic and modern technology — that allows it to transcend the dead-eyed cynicism so often associated with speculative fiction. It’s a much-needed departure from how games and tech startups, through decades of symbiotic exchange, draw from the belief that food is fuel, and even thrive on the assumption that we’re already halfway to dystopia.

The Culinarian quest is, if anything, an optimistic message that we should have more Debroyes and fewer Galveroches in food tech, and that more RPGs can and should approach food as more than throwaway consumables. The depth of the relationship between technology and video games has yet to be fully explored through the lens of food and eating, but the drive to maintain a state of focus, to prioritize efficiency, and the aversion to interrupting what Grossman describes as “blissful absorption in the machine,” is a phenomenon that many of us can relate to in 2022.

“I tried a sip of Huel once, that was as much as I could stand,” says Grossman. “I honestly can’t tell if they’re a good idea. On the one hand if you can’t change a culture that thinks of food as fuel, make a better fuel? Maybe it makes sense? But then it perpetuates the idea.”

Troov

Troov /cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70564729/ffxiv_12162021_182912_347.0.png)