Countries at COP28 approve climate disaster fund deal details in early breakthrough

Countries at the U.N. COP28 summit on Thursday agreed deal details for a disaster fund to help nations reeling from damages caused by the climate crisis.

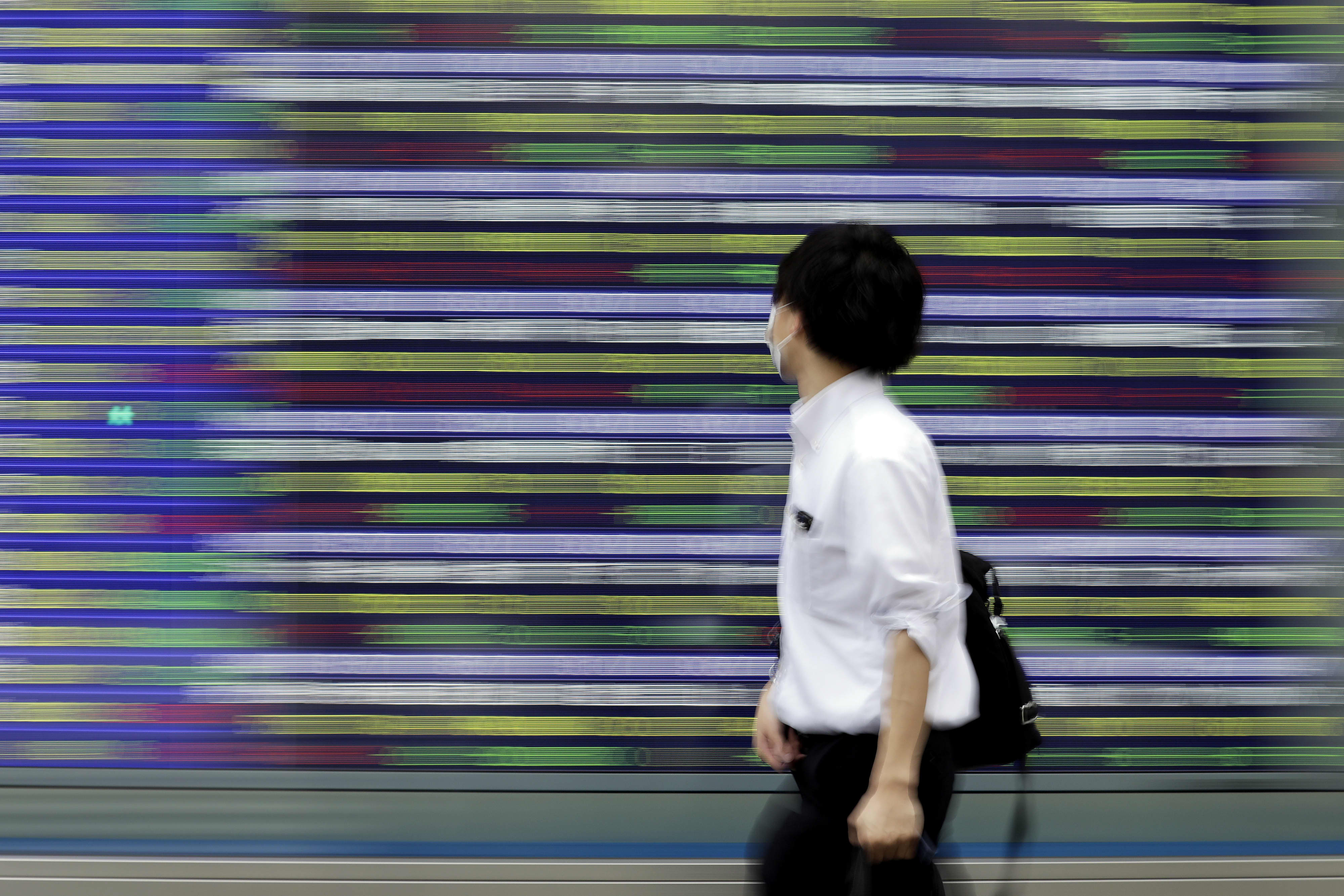

A man wearing a thawb walks past flags of nations participating in the UNFCCC COP28 Climate Conference the day before its official opening on November 29, 2023 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Sean Gallup | Getty Images News | Getty Images

Dubai, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES — Countries at the U.N. COP28 summit on Thursday agreed on deal details for a disaster fund to help nations reeling from damages caused by the climate crisis.

This agreement, struck on the opening day of the conference in the United Arab Emirates, builds on a deal for a loss and damage fund brokered at COP27 in Egypt last year — widely seen as a historic breakthrough and potential turning point in the climate crisis.

Many key arrangements were left unresolved at the time, such as who should pay into the fund, how large should it be and who should administer the money.

The operationalization of the fund on Thursday prompted a standing ovation from delegates in the audience.

So far, the pledges to the fund include $100 million from Germany, $100 million from the United Arab Emirates, $17 million from the U.S. and $10 million from Japan. The U.K. has also pledged sums into the fund.

Payments are made into the fund on a voluntary basis, and all developing countries are eligible to directly access the resources. The World Bank will be the interim host to the fund for a period of four years — an issue that has previously fueled tensions between high-income and low-income countries.

In emailed comments, Friederike Roder, vice president of sustainable development advocacy group Global Citizen, described the announcement of a loss and damage fund as a "historic decision," but added that "a fund is worthless without any dollars in it" and urged wealthy countries to step and announce significant pledges.

"The needs for loss and damage and other climate finance will continue to increase. This is why we also need, additionally, to tap into other financing sources, such as international taxes," Roder said.

High-income countries, which account for the bulk of historical greenhouse gas emissions, have long opposed the creation of a loss and damage fund to compensate low-income nations.

Advocates argue that the fund is required to account for climate impacts — including hurricanes, floods and wildfires or slow-onset impacts such as rising sea levels — that countries cannot defend against, either because the risks are unavoidable, or because they lack the financial resources to do so.

Avinash Persaud, special climate envoy to Barbados, said that the deal reflects "a hard fought historic agreement."

"It shows recognition that climate loss and damage is not a distant risk but part of the lived reality of almost half of the world's population and that money is needed to reconstruct and rehabilitate if we are not to let the climate crisis reverse decades of development in mere moments," he added.

A boost to momentum?

In Dubai, Alex Scott, an analyst at environmental think tank E3G, described the deal to establish a loss and damage fund as a "massive" breakthrough that reflected "a huge show of global cooperation."

"There is often a lot of skepticism at these multilateral spaces because they are often getting every country to agree, so they always end up being the lowest common denominator and end up with diplomatic speak that doesn't really make sense to people," Scott told CNBC.

"But this is very clear. This is a decision to establish the fund that they agreed they would try to establish last year. I think it will be a good momentum boost for the rest of the negotiations."

Policymakers will now need to reflect on how much they are willing to put into the fund, Scott said.

Low-income countries have previously called for sums of at least $100 billion a year by 2030, to be put toward the loss and damage caused by the climate crisis.

"I would expect some countries might hold back their pledges and wait until the very end, as part of the negotiating tactics to bring the final package together," Scott said.

JaneWalter

JaneWalter