Demythologizing Amida

A Shin Buddhist on using allegory to uncover the sacred context of our lives The post Demythologizing Amida appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Mahayana scriptures can seem bewildering, garish, even fanciful to modern readers. They seem to be remote from our ultimate concern, from our search for truth, from our longing to see things as they really are. Among such texts are the three Pure Land scriptures, which tell of an ancient Buddha named Amitabha (“Infinite Light,” or Amida in Japan). While we cannot endorse such texts as historical records, neither should we dismiss them as simply false or as fiction; rather, they awaken our creative imagination. They speak the language of myth.

A myth is a symbolic narrative that communicates important truths that cannot properly be revealed in any other way. To understand a myth we have to enter into it. To enter into the myth of Amida is to immerse ourselves within an imaginative narrative, like living through a poem. This is to recognize that there is a deeper dimension to human consciousness that transcends the scheming will. This is to recognize that there is a source of infinite value, an indefatigable, compassionate impulse that is eternally reaching out to bless us and fulfill itself through us. We can embrace this impulse or, rather, allow it to embrace us. We can be “grasped never to be abandoned” by Amida’s compassion, to use a refrain of Shinran, the founder of Shin, or True Pure Land Buddhism. The myth of Amida and their forty-eight vows affirm that, in spite of the painful and sometimes tragic events that may mark our lives, there is a benevolent, existential current that seeks to well up within us and to flow through us.

In his book, Jesus Christ and Mythology (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1958), theologian Rudolf Bultmann states, “myths give to the transcendent reality an immanent … worldly objectivity. Myths give worldly objectivity to that which is unworldly.” In other words, myths enable us to connect with the transcendent, the sacred dimension, the “great matter.” In Dynamics of Faith (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957), another theologian, Paul Tillich, writes that “humankind’s ultimate concern must be expressed symbolically, because symbolic language alone is able to express the ultimate.” Symbols and myths, he argues, are the authentic language of religious life and the only way in which the sacred can reveal itself directly. A symbol can never be fully “translated” into other terms but must be approached through the symbol itself. Since a symbol has multiple levels of significance and depth, its meaning can never be exhausted. For this reason, understanding them is a process that is never finished, never complete.

When symbols are structured into narratives, they form myths. The Pure Land of Sukhavati and its presiding Buddha Amida are symbols, and the narrative of Dharmakara, or Amida, that we encounter in the Pure Land scriptures is a myth. This means that we should not subject them to a literal interpretation. So how can this myth be understood in a meaningful way? The story of Amida and the creation of the Pure Land offer a myth of deliverance or liberation. They offer the promise of reconciliation with ourselves by means of a dynamic state of transformative awareness that embraces both our undoubted impulse toward self-transcendence and our inescapable fallibility. Through entering into the drama of this mythic narrative, we may go deeper into its significance in our own lives. To take a myth literally is idolatry. To interpret a myth, on the other hand, unleashes its transformative potential. Understanding a myth is never complete but rather refreshed and renewed each time we immerse ourselves within its narrative.

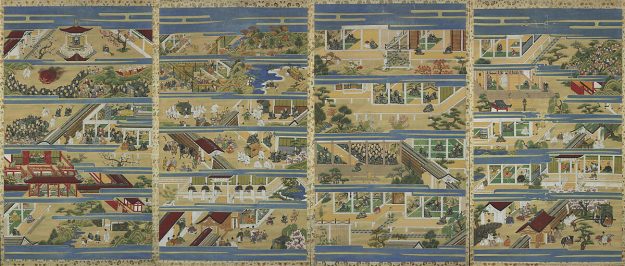

The Illustrated Life of Shinran (Shinran shōnin eden), Edo period (1615–1868), Japan. Set of four hanging scrolls; ink, color, and gold on silk. | Image Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Illustrated Life of Shinran (Shinran shōnin eden), Edo period (1615–1868), Japan. Set of four hanging scrolls; ink, color, and gold on silk. | Image Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.According to Bultmann, through interpreting myths we enable for ourselves a more authentic mode of existence. Myths draw on images and themes that are familiar to us and that belong to the visible world, albeit their intention is to evoke realities that are not visible and that call to us from beyond the horizon of the known. Rather than offering a description or explanation of the visible, outer world, myth is concerned with interiority, with human imagination. Myths are poetry.

Bultmann developed an approach to interpreting myths that he called “demythologizing.” This process does not aim to deconstruct myths, nor does it simply translate them into other terms (which would then make them redundant), but consists of a never-finished exercise in creative interpretation, an exercise that is always transformative. Through the practice of demythologizing, we may harvest the existential riches latent within myths.

In approaching symbols and myths, we must commit to a kind of wager. In this case, we must wager on the fact that Amida’s myth has something significant to say to us about our existence and that through opening ourselves up to its significance, through entering into it, we will be recompensed with an enlarged self-understanding. While we remain outside the myth, as a spectator, it can never come alive for us as a world of living significance. We will never know what the ocean feels like until we plunge in. Understanding begins not by means of a bird’s-eye view (which is impossible), but from a particular and restricted standpoint. We may then go about the process of verifying the myth by saturating it with intelligibility. This results in a transformation of consciousness. Through their interpretation, symbols and myths assume the gravity of existential agents; they become means by which we can bring alive our understanding of what it means to be human and what is of maximum value to us.

What could it mean for us to demythologize, or deliteralize, the myth of Amida and the Pure Land? It would mean to understand it not as a narration of historical events that happened a long time ago but as revealing something about the nature and purpose of human existence and of the possibilities that may unfold within it. The Pure Land is life understood as a field of going for refuge. From our side, from the inside, the world manifests itself to us as infused with sacred meaning, as a call toward enlightenment. The world unfolds before us as a dimension that not only enables but also invites, and even enacts, liberation. The Pure Land is the present moment sacralized. The Pure Land is epiphany.

The Pure Land is not necessarily an external, material world, but rather a spiritual dimension that we can begin to inhabit as we open ourselves to the blessing of Amitabha. In The Collected Works of Shinran, the Shin founder offers a tantalizing reflection in relation to the inside-or-outsideness of the Pure Land when he writes: “Hence we know that when we reach the Buddha-land of happiness, we unfailingly disclose buddhanature.” Buddhanature is more commonly interpreted as a potential within us; something that can come alive as we become spiritually sensitized, like a seed that grows and then flowers. Yet Shinran appears to be saying that awakening to our buddhanature is in fact the same as being reborn in the Pure Land. We might say, perhaps, that the Pure Land is neither inside us nor outside but both; it discloses to us the sacred context of our lives.

To offer a different perspective, the Pure Land might also be seen as a kind of cosmic sangha, which is inconceivably vast, and infinitely more refined, a field of blessing, saturated with value and significance. This suggests that, instead of being a place, the Pure Land articulates a relation, even the spirit of kalyāṇa mitratā, or spiritual friendship. The Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa declares that the Pure Land is this very world. We see it as impure owing to our distorting perceptions and afflictions. Amida and the Pure Land are not really separate from one another, neither are they separate from us. To enter the Pure Land is to enter into Amida’s body, even to be reconstituted by Amida as Amida. It means to be welcomed into Amida, but not in such a way that submerges or dismembers us. Rather, it entails recognizing more completely how we are intimately connected to others as we realize our solidarity with them, as we awaken to our shared cares, fears, and longings. In his Collected Works, Shinran articulates this sentiment:

When a foolish being of delusion and defilement awakens shinjin [true entrusting],

He realizes that birth-and-death is itself nirvana;

Without fail he reaches the land of immeasurable light

And universally guides sentient beings to enlightenment.

Amida symbolizes the sacred world breaking in on us or erupting within us. Amida is a transcendent factor that works upon or through us but which never fully belongs to us. Better, it can never be appropriated by us. Nor can it in any way be manufactured or contrived. Amida is pure compassion reaching out to all beings through us. Amida’s infinite light eternally shines upon all without exception.

With the permeating light of allegory, it becomes easier to see all the areas of greed, anger, and desire that exist within as well as the sacred context of our lives. The myth of Amida and the Pure Land do not contradict historical or factual truth, but rather they enable us to wake up to the value and scope of our human existence.

FrankLin

FrankLin