Don’t judge Apple’s VR headset too soon

Illustration: The VergeJust when the metaverse had mostly faded from the headlines, a heavily rumored new product launch appears poised to bring it roaring back. Today let’s talk about what’s happened in the world of virtual and mixed reality...

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24401979/STK071_ACastro_apple_0002.jpg)

Just when the metaverse had mostly faded from the headlines, a heavily rumored new product launch appears poised to bring it roaring back. Today let’s talk about what’s happened in the world of virtual and mixed reality since last we left it and whether Apple can find mainstream uses for headsets that go beyond the games that have defined it so far.

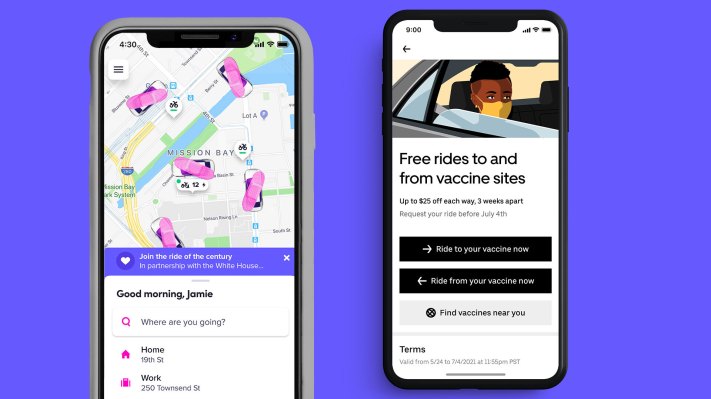

Monday marks the start of Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference. Unlike most years, when coming software updates dominate the keynote, this year hardware is expected to take center stage. After more than seven years of development, Apple is reportedly set to unveil the Reality Pro, a roughly $3,000 headset that aims to serve a variety of productivity uses. (Apple almost certainly will not use “the metaverse” in any marketing materials, though, however convenient it might be for those of us writing about the space.)

According to Bloomberg’s Mark Gurman, who has been on the reporting run of his career revealing almost every detail imaginable about the device, the Reality Pro will offer VR FaceTime calls, immersive video, and an external display for connected Mac computers, among other features. As of January, though, Gurman reported that the company hadn’t yet discovered a “killer app” for the device — an experience compelling enough both to justify the high price tag and drive everyday use.

Enthusiasm for some kinds of digital experiences has dimmed

While reporting on VR often focuses on the middling sales numbers, the usage numbers should arguably be of greater concern. Last year, the Wall Street Journal reported that six months after purchase, more than half of Meta’s $400 Quest headsets were no longer in use — a testament to how quickly the novelty of the experience tends to fade. (Or, perhaps, how quickly the many inconveniences of using the device pile up.)

It has now been almost two years since Mark Zuckerberg, in an interview with me, announced that the company then called Facebook would pivot into building the metaverse. A year and a half into the pandemic, with hundreds of millions of people still keeping close to home and away from the office, the move was perfectly timed. Video chat and digital entertainment were then two of the only things tethering us to other people. It was not much of a stretch to assume that eventually, next-generation hardware and software would both radically improve those experiences and command more of our time as they did so.

A lot has changed since 2021, though. As the world has gradually re-opened, enthusiasm for some kinds of digital experiences has dimmed. Zoom, which served as a kind of proxy for investors’ belief in internet-enabled productivity, peaked at $559 per share in October 2020 — and today trades at $67.83. Vast, interconnected worlds have captured mass attention in Roblox and Epic Games’ Fortnite, but remain stubbornly standalone, 2D experiences. (Roblox stock is also now worth less than a third of its peak price.)

Facebook, which was so determined to lead this hoped-for platform shift that it rebranded itself to Meta, today owns roughly 80 percent of the market with its Quest and Quest Pro headsets, according to estimates from market research firm IDC. But headset sales are down 54.4 percent year over year, Reuters reported today, and revenue from Meta’s Reality Labs division was down 50 percent last quarter compared to the previous year.

Image: Amelia Holowaty Krales / The Verge

The launch of the $1,500 Meta Quest Pro last year was intended to expand the market for headsets beyond the gaming uses that make up most of the time people spend with them. But sales estimates suggest that the response to features like virtual desktops and VR conference rooms has been anemic. (On an early episode of Hard Fork, we convened in one of those VR conference rooms; I remember the experience primarily for how difficult it was to get everyone’s setup working.)

One of the great gifts of the AI mania of the past six months is that it has shown us, clear as day, what it looks like when consumers actually get excited about something. ChatGPT is a product people bring up to me in everyday life before they even find out I’m a tech reporter; roughly seven months after launch, 12 percent of Americans have already used it for work. There’s something deeply funny about the fact that, after billions of dollars spent hyping up VR and crypto, the product that actually captivated the world’s attention again was a text box.

All of which is to say: Apple has its work cut out for it here. The company’s near-term ambitions are prudently cautious. (“It initially hoped it could sell about 3 million units a year out of the gate, but it’s pared back those estimates to about 1 million, then to 900,000 units,” Gurman reported last month. “By comparison, the company sells more than 200 million iPhones a year.”) Eventually, though, the company envisions a world where knowledge workers wear headsets like this all day.

Only through steady iteration do the company’s devices eventually break through

That won’t be possible anytime soon. The headsets appear too bulky, the battery life too short, and the reported design too laden with obvious compromises to attract all but the most enthusiastic early adopters. That, coupled with the lack of a killer app, suggest the Reality Pro will benefit Apple more as a reason to lure customers into the demo area at the company’s retail stores than as a business on the level of the iPhone.

Meanwhile, Meta will press its advantage at the lower end of the market. Today the company said the Meta Quest 3 would go on sale this fall for $500, with more powerful processor, an improved display, and a slimmer design. (The company also cut the price of its Quest 2 headset by $100.) It remains to be seen whether either Meta or Apple can solve the tendency of consumers who have bought the devices to toss them into a drawer and forget them. (My humble request is that either company simply make VR chat as compelling as what Google is doing with light-field displays in Project Starline.)

All that said: Monday won’t be the right time to judge whether Apple has succeeded or failed. Nor will be the day that the Reality Pro goes on sale. From the iPhone to the Apple Watch, the company’s 1.0 launches often arrive with obvious limitations. Only through steady iteration — and support from third-party developers — do the company’s devices eventually break through. I waited to buy an Apple Watch until the Series 5, the first model that had an always-on display. Today I can’t imagine not having the device on my wrist. The division made $41 billion last year. It got there.

Barring ChatGPT becoming sentient, it will likely be four or more years before any company manages to solve the technical and creative challenges necessary to usher in a true VR-centric platform shift. But as disappointing as the metaverse has been in some respects, the incremental improvements from year to year are evident to anyone willing to look.

Whatever hurdles it has to overcome, Apple usually gets hardware right in the end. The thing to keep in mind on Monday is that, in this case, the end is still a long time away.

Koichiko

Koichiko