Everything Everywhere All At Once is an immigrant horror story about tax season

Everything Everywhere All At Once. | Image: A24Even a sci-fi tale about the multiverse can’t escape taxes Continue reading…

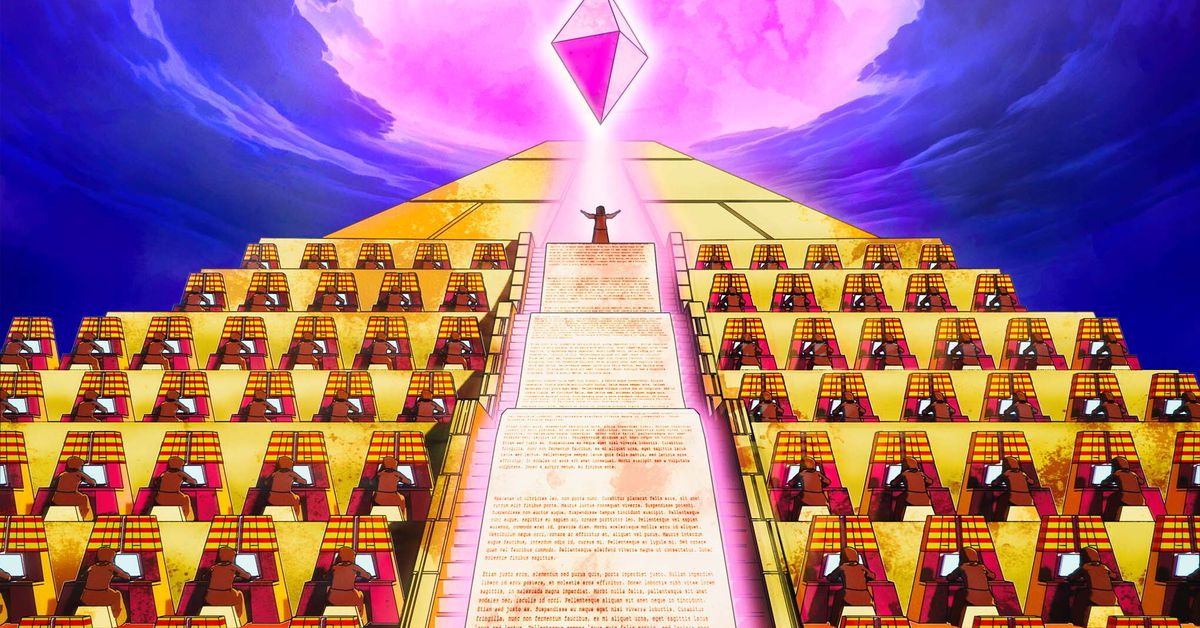

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70831275/EEAAO_00993_R.0.jpg) Everything Everywhere All At Once.Image: A24

Everything Everywhere All At Once.Image: A24

Filed under:

EntertainmentEven a sci-fi tale about the multiverse can’t escape taxes

Nothing is certain but death and taxes, and the science fiction film Everything Everywhere All At Once is in part a horror story about the latter. The tax office is the final boss for every immigrant family who has too many generations living under one roof, receipts that are too incriminating to explain, or breadwinners with a limited grasp of English. It was the first time that I had ever seen one of my deepest fears on the silver screen: that my life was too messy, too foreign, too fucked up for this country. EEAAO exposes Asian America’s most embarrassing insecurities and loves us anyway.

Everything Everywhere All At Once is a science fiction film about a beleaguered laundromat owner who is thrown into an interdimensional war against an entity of chaos. But it’s also an action film that pays homage to Hong Kong’s martial arts movies, a thriller, a romance, and a comedy. EEAAO is a smorgasbord that shouldn’t work, but it does. That’s because the movie has a consistent villain throughout the entire plot: the black circle on the center of the Wangs’ tax returns. These diligent immigrants can overcome any adversary, but their taxes are a white whale that can never be surmounted.

Right at the beginning of the film, the Wang family launches into Frankensteined sentences of Mandarin, Cantonese, and English. They weren’t speaking slowly either — instructions and thoughts were being shot back and forth like in a badminton game. And the Wangs lived in an apartment that was located in the same building as their laundromat. Even before Evelyn Wang (Michelle Yeoh) was jumping between multiverses, she was seamlessly switching between her work and domestic life. Evelyn wasn’t necessarily an innately powerful dimension traveler; immigrant life was the best practical training that she could get.

But even the hyper-competent immigrant housewife had her kryptonite: tax season. Tax fraud was a trickling fear that superseded both education and personal integrity, a test for non-Americans to fail. The Wangs were not the “typical” American family that American institutions were designed for. They were a multilingual family with mixed citizenship status. Instead of a tax preparer, they had piles of memo pads, a child interpreter, and confectionery gifts. They had to be liars and fakers to survive a country that historically excluded Chinese people from public life.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23434970/EEAAO_03759_RC.jpg) Everything Everywhere All At Once.Image: A24

Everything Everywhere All At Once.Image: A24

The “model minority myth” teaches white America that Asians are the perfect immigrants and offers them a devil’s bargain: hide their dirty laundry and this country would treat them with some amount of dignity. Evelyn chased this respectability even when the pressures were clearly grinding her mental health and her relationships to dust. While the Wangs had it better than less favored groups of immigrants, they were still considered suspicious foreigners by American institutions.

As I watched Waymond Wang (Ke Huy Quan) slide a box of bribery cookies to the tax auditor, I remembered what my aunt taught my mother about speeding tickets: cops may be lenient to women who fake cry. This is the reality for immigrant families who didn’t come from wealth or whose children didn’t make magna cum laude at Harvard. Survival is built upon numerous “harmless” white lies, such as Evelyn’s claim that her karaoke expenses were tax-deductible.

While Evelyn’s family has immigrant struggles, they’re just close enough to mainstream acceptability. All she had to do was lie about her daughter’s girlfriend, exaggerate to her customers about the laundromat’s success, and hide the divorce papers from her husband. If America would not accept her for who she was, then her only choice was to become someone else by any means necessary. Even if that involves a bit of cross-dimension jumping.

In a different timeline, Alpha Evelyn said “fuck it” and invented multiverse travel. America is a country where people can do everything and anything. Why not do it all at once? By taking absurd actions such as eating a tube of lip balm, dimension-jumpers can synchronize with an alternate version of themselves. Doing so allows them to access new experiences, such as martial arts or dexterity with kitchen utensils. Waymond tells Evelyn that she can do all of these things because she is talentless. I disagree. I think she is driven to become all of these personas because she wants to be anyone but the small-minded laundromat owner who can’t see beyond the next bill payment. Evelyn isn’t stupid. She knows better than anyone that she’s falling through the cracks. And if an Asian immigrant isn’t a capital S Somebody in America, then they might as well not be here at all.

EEAAO is about a lot more than taxes. The film grapples with the question of whether Evelyn deserves the American life that she has. She’s not good at English or accounting. Their business racks up far too much debt. As an alternate Waymond tells her, she’s not particularly good at anything. Her father keeps kicking Evelyn down for being indecisive. If she had just been smarter, stronger, or more charismatic, then maybe she could have more than a broken family and a pile of back taxes. Every time she warped into a different life, I wondered if she could have been happier in the other one. Maybe the Evelyn in the universe where everyone had hot dog fingers had a better marital life than the Evelyn who married Waymond.

Most days, I feel exactly like Evelyn does. Despite the immense number of accomplishments I have relative to my struggles (English was never my first language either), it always feels like I cheated the system. Like I stumbled into the career that I have simply for being too pigheaded to accept “no” for an answer. As a laundromat owner, how many times must she have been denied a loan or side-eyed by neighbors who didn’t think Chinese people belonged?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23434973/EEAAO_00503_R.jpg) Everything Everywhere All At Once.Image: A24

Everything Everywhere All At Once.Image: A24

There’s an expression in Chinese: 机不可失,时不再来. It means that once you fail to take advantage of an opportunity, it’s lost forever. The film shows that Evelyn had many opportunities to become greater than a laundromat owner. She could have chosen not to run away from home to marry the boy she loved. She could have divorced Waymond in America. She could have tried to become a chef. She could have trained herself physically — should have, could have, never did. The multiverse is not truly a source of empowerment for Evelyn but a primordial soup of all of her past regrets.

Evelyn’s daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu) eventually convinces her mother to let go of her burdens. The special effects are triumphant as Evelyn serves Waymond the divorce papers, surrenders her daughter to the insurmountable chaos, and smashes up her own laundromat. It’s supposed to feel a little cathartic for both the protagonist and the audience. Yet, at the same time, it feels sad. Her laundromat wasn’t just oppressive — it was her pride as the family breadwinner. Even if she tried to abandon the life she made for herself, she’s not truly a movie star or a karate master like in the other universes. She’s a laundromat owner who has a dysfunctional family and a pile of back taxes to pay.

In many films about women who struggle in their marriages, the woman triumphs when she walks away. When Evelyn divorces her husband in one dimension and allows her daughter to leave in another, I thought that was where the film was headed. But EEAAO is not a callous movie, and directors Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert understand that walking away does not liberate Evelyn. By walking away, she’s destroying everything that she had ever fought for. When people throw away bad things, sometimes they end up throwing out the good, too.

I cried so many times during this movie. I didn’t think I had any more to give by the time the final act rolled around. But I was wrong. At the end of the movie, Evelyn is able to accept that she doesn’t need to have her life together. In this capitalist hellscape, nobody has their life together. As long as there’s a single person who can accept you for being a messy freak (if you can accept others for being messy freaks), then the rest of it doesn’t matter. EEAAO rejects the premise that we must be perfect in order to be loved. I used to think that being told that I could be the best version of myself was love. But after watching this movie, I felt that I was worthy even if I didn’t try to be the master of my own destiny.

The next time that I really need an extension with the IRS, I’m allowing myself to request one. Nobody’s life is tidy. We shouldn’t punish ourselves for imperfect tax returns.

JimMin

JimMin