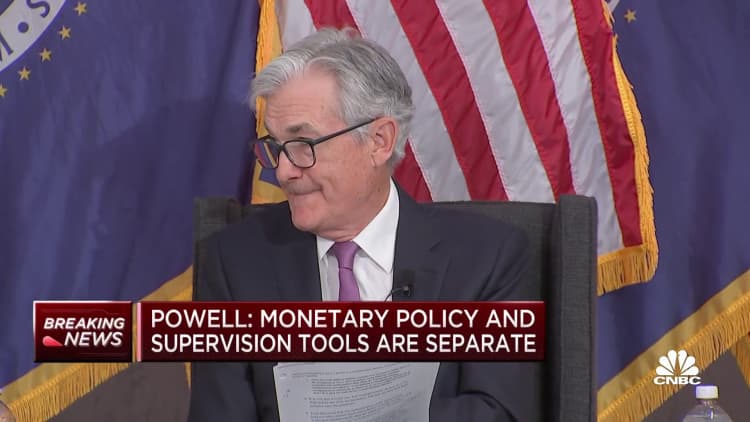

Fed Chair Powell says rates may not have to rise as much as expected to curb inflation

Powell spoke Friday at a "Perspectives on Monetary Policy" panel in Washington, D.C.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said Friday that stresses in the banking sector could mean that interest rates won't have to be as high to control inflation.

Speaking at a monetary conference in Washington, D.C., the central bank leader noted that Fed initiatives used to deal with problems at mid-sized banks have mostly halted worst-case scenarios from transpiring.

But he noted that the problems at Silicon Valley Bank and others could still reverberate through the economy.

"The financial stability tools helped to calm conditions in the banking sector. Developments there, on the other hand, are contributing to tighter credit conditions and are likely to weigh on economic growth, hiring and inflation," he said as part of a panel on monetary policy.

"So as a result, our policy rate may not need to rise as much as it would have otherwise to achieve our goals," he added. "Of course, the extent of that is highly uncertain."

Powell spoke with markets mostly expecting the Fed at its June meeting to take a break from the series of rate hikes it began in March 2022. However, pricing has been volatile as Fed officials weigh the impact that policy has had and will have on inflation that in the summer of last year was running at a 41-year high.

On balance, Powell said inflation is still too high.

"Many people are currently experiencing high inflation, for the first time in their lives. It's not a headline to say that they really don't like it," he said during a forum that also featured former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke.

"We think that failure to get inflation down would, would not only prolong the pain but also increase ultimately the social costs of getting back to price stability, causing even greater harm to families and businesses, and we aim to avoid that by remaining steadfast in pursuit of our goals," he added.

Powell characterized current Fed policy as "restrictive" and said future decisions would be data-dependent as opposed to being a preset course. The Federal Open Market Committee has raised its benchmark borrowing rate to a target of 5%-5.25% from near zero where it had sat since the early days of the Covid pandemic.

Officials have stressed that rate hikes operate with a lag of a year or more, so the policy moves have not completely circulated through the economy.

"We haven't made any decisions about the extent to which additional policy funding will be appropriate. But given how far we've come, as I noted, we can afford to look at the data and the evolving outlook," Powell said.

Monetary policy in large part has been geared toward cooling a hot labor market in which the current 3.4% unemployment rate is tied for the lowest level since 1953. Inflation by the Fed's preferred measure is running at 4.6%, well above the 2% long-range goal.

Economists, including those at the Fed itself, have long been predicting that the rate hikes would pull the economy into at least a shallow recession, likely later this year. GDP grew at a less-than-expected 1.1% annualized pace in the first quarter but is on track to accelerate by 2.9% in the second quarter, according to an Atlanta Fed tracker.

Powell spoke the same day that the New York Fed released research showing that the long-range neutral interest rate — one that is neither restrictive nor stimulative — is essentially unchanged at very low levels, despite the pandemic-era inflation surge.

"Importantly, there is no evidence that the era of very low natural rates of interest has ended," New York Fed President John Williams said in prepared remarks.

Lynk

Lynk