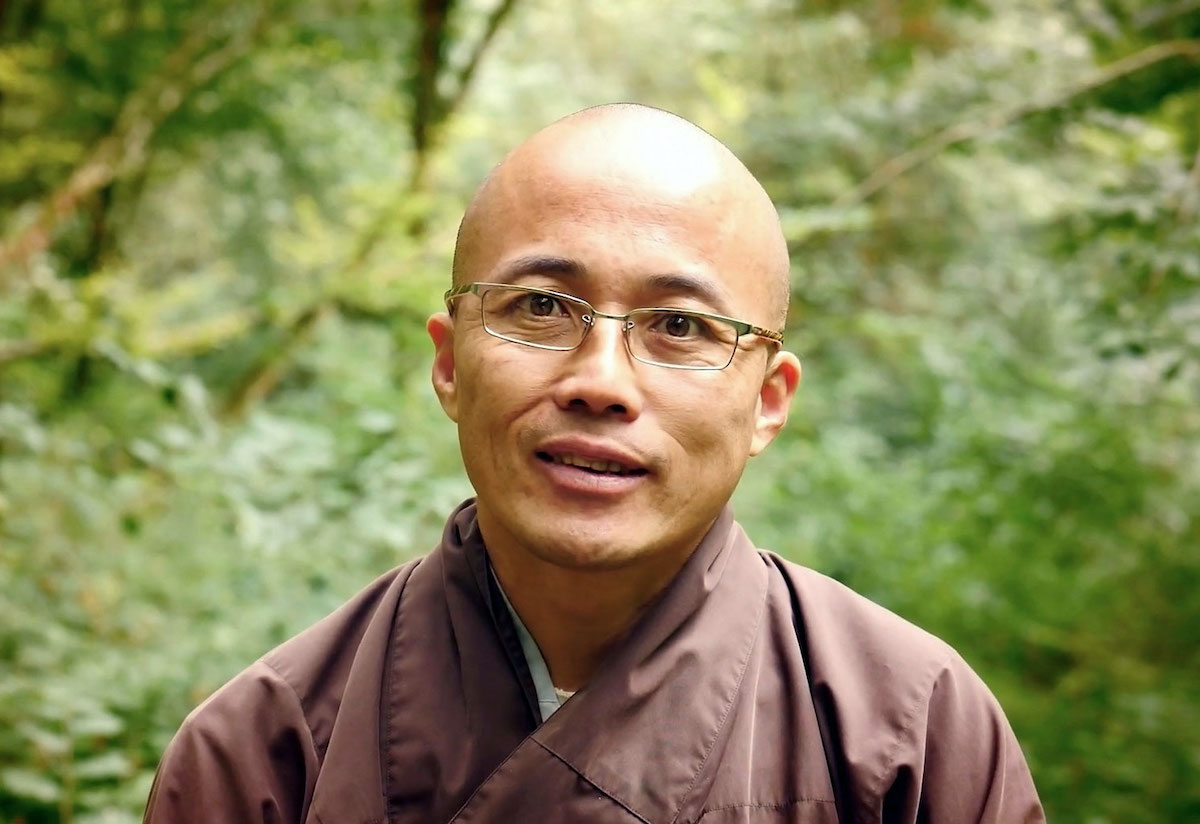

Have we understood the Buddha? (Part II)

In this article we continue to explore the ways to study and practice Buddhism (Buddhist methodology) to help us become soulmates of the Buddha.

In this article we continue to explore the ways to study and practice Buddhism (Buddhist methodology) to help us become soulmates of the Buddha.

The Two Truths二諦

Relative truth (saṃvṛti-satya) 世俗諦

This is the conventional truth, a relative truth grounded in agreed-upon concepts: ‘we’ and ‘they’, life and death, beginning and end, left and right, suffering and happiness. In conventional terms happiness is not suffering, I am not you, and the father is not the son. There is a kind of truth in these claims, but it is only a relative truth. According to the relative truth, this lies outside of that, father lies outside of son, the subject is not the object, and the creator is not the created.

Absolute truth (paramārtha-satya) 勝義諦

When we look deeply we see another truth. For example, looking deeply into the son we see the father. Were it not for the father, there would be no son; if there were no son, we could not call that person father. We cannot remove the father from the son or the son from the father. Similarly, we cannot take left out of right or right out of left. We cannot have the perceived without the perceiver and we cannot have the perceiver without the perceived. We cannot have the soul without the body and we cannot have the body without the soul. That is the absolute truth, according to which “this” lies in “that.” Looking into the flower we see the sun; the sun does not lie outside of the flower. The child and the parents interare; they condition each other. Thanks to the practice of contemplating conditioned genesis[1], we can see the absolute truth.

When we study and practice Buddhism, we receive teachings in terms of both the conventional and the absolute truth. We should not be surprised, therefore, that one sutra operates on the level of the relative truth and another within the absolute truth. When we read in one sutra that we are born and die, and in another sutra that there is no birth and death, we do not see it as a contradiction. We are also not surprised when the Buddha refers in one passage to Ānanda and the Buddha as two separate selves, and elsewhere the Buddha teaches no separate self.

David Bohm, a British physicist has spoken of two orders: the explicate order and the implicate order. As with the absolute and relative truths, these orders at first seem to contradict each other. However, when we look deeply, we can move seamlessly between them.

The explicate order means that one thing lies outside of another: left lies outside of right and son lies outside of father. When we look deeply, though, we see that things are not like that; we touch the implicate order. One thing contains so many other things. The son does not just contain the father but also the mother and all the ancestors.

In the field of quantum physics there are also truths that seem at first to contradict the truths of classical science. Classical or Newtonian physics have been applied successfully for many years across fields such as engineering and technology. But the truths that are now being discovered in particle or quantum physics are very different. If we can’t let go of the truths that we have learnt in Newtonian physics, we won’t be able to understand particle physics. We could think that this electron is different from that electron, that one lies outside the other. The truth is that this electron lies within that electron. That is the implicate order according to which nothing can exist separate from everything.

Between the implicate and the explicate order there is a dividing line. People ask: how can we bridge the gap between the two orders, between Newtonian and quantum physics? That is one of the biggest questions in present-day physics. Buddhism has an answer: both kinds of truth can be applied successfully in life and the two kinds of truth do not contradict each other.

Separate investigation of the nature and the appearance

The separate investigation of nature and appearance is a methodology discovered by the ancestral teachers and handed on to us. In our studies and practice, we must distinguish the nature (svabhāva) from the sign or appearance (lakṣaṇa). In Kantian terms, it means that we investigate the noumenal and phenomenal separately. The nature is the ontological ground, the noumena; the appearance is the phenomenal world. In our investigation we should not mix the two up. When we are investigating the ontological, we only talk in ontological terms. Likewise, when we are investigating the phenomenal world, we only talk in phenomenological terms.

In the Dharmalakṣaṇa school of the Buddhist Manifestation-Only school, there is a list of the one hundred objects of mind (dharmas). The phenomenal world is divided into 100 different categories; for example, form (rūpa), sound, scent, touch, mind objects, eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind. Eyes are a conditioned object of mind (saṃskṛta dharma) and so is the flower, the table, and our body, because they are made up of things that are not themselves.

There are also unconditioned objects of mind (asaṃskṛta dharmas) like space and nirvāṇa. Strictly speaking, though, nirvāṇa is not an object of mind. To say that nirvāṇa is an object of mind is to mix up the nature with the appearance. Nirvāṇa belongs to the ontological world and we cannot put it on the same level as things belonging to the phenomenological world. Similarly, Christian theologians say that God is the ground of being. We can talk about the flower as being or not being, as beautiful or not beautiful, but we cannot talk about God as being or not being, as good or not good. In other words, we cannot mix up the noumenal and phenomenological. When we talk about the ontological we cannot use terms like beginning, end, large, small, high, low, beautiful, or ugly; we can only use these terms in relation to the phenomenological. In the same way, we can say that the wave, which represents the phenomenal world, is big or small, high or low. However, the ocean water, which represents the ontological, cannot be talked of in these terms.

From the phenomenological to the ontological

We must find a skillful way to move from the phenomenological into the ontological world and back again so that we can see that the two are not in opposition. We could say that the phenomenological world is the ontological world, but the phenomenological is different from the ontological. In the phenomenological world there is being, non-being, high, low, beautiful, and ugly. Even though we cannot use these terms in relation to the ontological, we need the phenomenological in order to touch the ontological. Just as we cannot have the waves if we take away the ocean water. Even though the ontological and phenomenological are two different worlds, they are also one.

A 10th century Vietnamese Zen master (d. 950) named Vân Phong (Cloud on the Mountain) of the Vô Ngôn Thông school taught:

-There is the world of birth and death, but there is also the world of no birth and no death. A practitioner of the way needs to go back to the world of no birth and no death.

A disciple named Thiện Hội (Understanding of Goodness) asked:

-Where can we find the world of no birth and no death?

The Zen Master replied:

– You find the world of no birth and death right in the midst of the world of birth and death.

In other words there is not a world of no birth and no death that lies outside the world of birth and death. From the phenomenological we go to the ontological.

When I was twenty-four years old, I wrote a poem with the line:

From the world of phenomena the boat returns to the noumenal1

From the phenomenal world we gradually move into the noumenal. Nirvāṇa is found in the midst of birth and death. If we run away from the world of birth and death, we shall not find nirvāṇa. If we change our way of looking at things, then saṃsāra will become nirvāṇa. And the methods we use to change our way of looking are the Middle Way2 and the insight of interbeing.

Kālāma (Kesaputtiya) Sutta3

The Kālāma (Kesaputtiya) Sutta is a wonderful and well-known sutra. The Buddha gave this teaching to several young members of the Kālāma after they came to the Buddha and said:

-From time to time a spiritual teacher will pass by here. We invite them to stay a little and give us a teaching. They all say that their philosophy is the best and the truest and that the philosophy of all other spiritual teachers is wrong. So we do not know who to believe. Please, Buddha, teach us what we should do.

The Buddha’s response proves that he had a scientific approach. The Buddha said:

Young people of the Kālāma clan, do not be in a hurry to believe anything you hear, even if it has been written down in the scriptures or is what a very famous teacher says.

Whenever you hear a teaching, you must look deeply and carefully, using your intelligence, to discover whether it is reasonable and true. You must apply the teaching in your life, and if the teaching brings peace, joy, liberation, and happiness, you can have confidence in it. If it doesn’t bring these things, what reason is there for you to believe in it?

In the West, this sutra has been called The Buddha’s Charter of Free Inquiry. In the same vein, the ancestral teachers of the past also encouraged us not to explain the sutras by digging into them word by word, but by using our understanding: If you rely on the scriptures to explain the true meaning of the teachings, you do an injustice to the buddhas of the three times 依經解義三世佛冤. When studying the sutras, we must use our understanding and not be caught in semantics. We can reflect, look deeply, and apply what we have learnt; then our faith in the teaching will be true faith.

Konoly

Konoly