Her Liberation: Bhikkhuni Dhammawati Guruma

Bhikkhuni Dhammawati Guruma broke through oppressive patriarchal barriers to pursue spiritual freedom. Wendy Garling tells her inspiring story. The post Her Liberation: Bhikkhuni Dhammawati Guruma appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

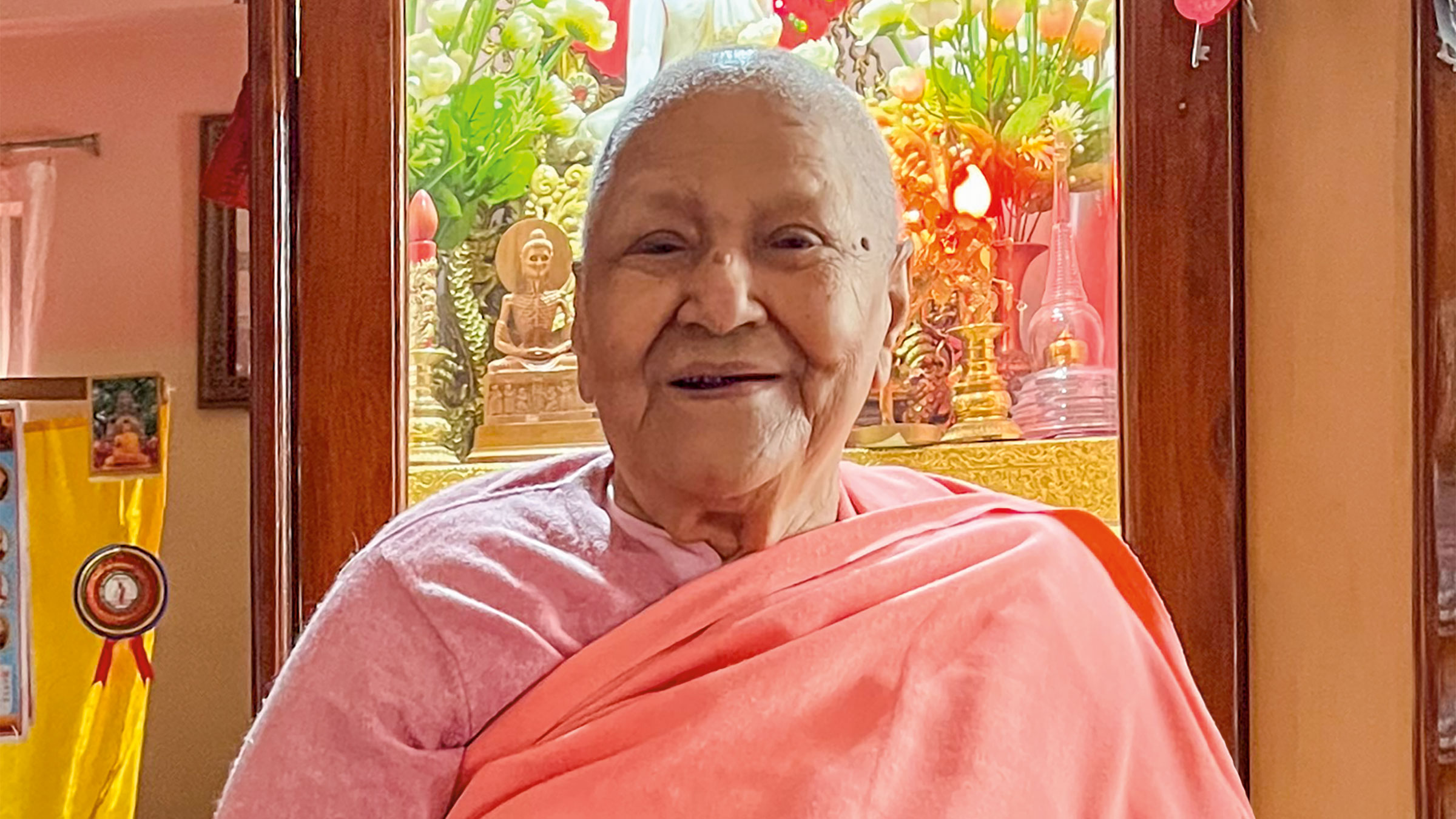

I’m ushered into a small, crowded shrine room where there’s an abundance of offerings, Buddha statues, and images of Buddhism’s first nun, Mahaprajapati Gautami. I’m here to meet Bhikkhuni Dhammawati Guruma, the legendary ninety-year-old nun who’s widely credited with reviving authentic Theravada Buddhism in Nepal and opening doors for the religious education of women and girls.

A diminutive figure swathed in pink and barefoot, Guruma silently enters the room and takes a chair by the shrine. Her demeanor is gracious, if weary, perhaps from the many visitors who in recent years have found their way to her monastic enclave in central Kathmandu. My translator explains that I’ve come from the United States to lead a group of Buddhist women on pilgrimage to Buddhism’s motherland in southern Nepal, the birthplace not just of the Buddha, but also of his matrilineal forebears, including his two mothers: Mahamaya, the Buddha’s birth mother who died shortly after childbirth, and her sister Mahaprajapati, who raised him. Our pilgrimage, the translator explains, would continue from Kapilavastu, where Mahaprajapati first requested monastic ordination on behalf of herself and five hundred women, to Vaishali, India, where the Buddha eventually granted their request.

Delighted by news of our pilgrimage, Guruma breaks into a smile, eyes shining, and begins to talk animatedly and at length about Mahaprajapati as a role model and pioneer who broke through oppressive patriarchal barriers to pursue her goal of spiritual freedom. Her emotion is deeply felt, and it’s not hard to see why. Despite 2,500 years between them, the parallels between the lives of Guruma and Mahaprajapati are striking.

In 1934, Guruma was born Ganesh Kumari Shakya to an ethnic family group that considers themselves direct descendants of the Buddha’s own Shakya clan. Like Mahaprajapati, she grew up in a loving family of privilege at a time when there were no prospects for girls beyond marriage and motherhood. In the early twentieth century, the ruling “ranas” or warlords of the Kathmandu Valley not only forbade education for girls—it was considered “immoral”—but also severely restricted their movements outside their homes. Guruma describes what that was like. “We had to remain hidden,” she says. “The army would patrol the streets, and if they saw us looking out the window, they would arrest us and take us away.”

Yet the only “true suffering” in her childhood, Guruma tells me, was lack of access to authentic buddhadharma. The Newari religion was mostly a hybrid of tantric Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism mixed in with regional beliefs, and the warlords did not allow public teachings of Theravada Buddhism. But, as a child, Guruma gained a keen interest in Theravada texts after learning Pali verses from her mother.

When restrictions against Theravada gradually loosened, Guruma—at age thirteen—had a transformative experience hearing discourses from a traveling Burmese monk. Her imagination took flight when she learned that literacy and Theravada monasticism were equally available to girls and boys in Burma. In that moment, it became clear that a life devoted to the dharma was possible. “I thought and cared about nothing else after that,” she says.

Girl power and ingenuity fueled Guruma in the following years. When the visiting Burmese monk offered to escort her to Burma and assure her admission to a nunnery, the young Guruma ran away from home. This angered her father, and he was determined to retrieve her. Out of love for him, Guruma decided to release him from his agony by making it clear she wasn’t going back to lay life. And with that, she shaved her head, took ordination in India as a nun, and received the name Dhammawati. Only fourteen years old, she severed all familial identity and ties.

Mahaprajapati was the stepmother and maternal aunt of Siddhartha. Later she went on to become the first Buddhist nun. Painting by Maligawage Sarlis / Photo by MediaJet

Mahaprajapati was the stepmother and maternal aunt of Siddhartha. Later she went on to become the first Buddhist nun. Painting by Maligawage Sarlis / Photo by MediaJetSo began a perilous journey on foot to Burma, with dangers and determination that can be likened to Mahaprajapati’s own arduous trek to Vaishali in pursuit of acceptance into her son’s monastic sangha millennia before. While Mahaprajapati traveled in the company of five hundred women, Guruma traveled with her monk escort and scores of elephants, led by mahouts (elephant traders) who assisted them in traversing the treacherous mountainous terrain and jungle (think pythons and tigers), while evading border guards. Finally, crossing into Burma after two exhausting months, she was promptly thrown in jail.

Here Guruma pauses, her gaze softening as memories return her to that brave young girl all alone in a filthy, crowded jail cell infested with bugs in a faraway country where she did not speak the language.

“Were you afraid, Guruma?” I ask.

Nodding slowly, she describes this as the lowest point in her journey. Her confidence finally wavered, and the trauma drove her into prayer. But suddenly, her experience shifted, and an image of the Buddha appeared before her in a dream, radiating blessings as he reassured her that she’d soon be released. Sure enough, two days later a kindly, high-ranking government official, facing the unprecedented predicament of determining the fate of an incarcerated, runaway child-nun, took her under the protection of his own family for six months while her petition to gain legal entry to Burma and placement in a nunnery could be sorted out. “I don’t know how he heard about me,” says Guruma, “except through the blessings of the Buddha.”

In 1949 at the age of fifteen, Guruma, affectionately known as Manipo (“Nepalese girl”), realized her dream and was admitted to the esteemed nunnery of Khemarama in Moulmein, Burma, where she flourished in her studies of the Theravada Tripitaka for the next twelve years. Following many academic honors and widespread renown, she was awarded the highest degree of Dhammachariya, a first for a foreign national and among the first for women in Burma.

In 1963, Guruma felt the time had come to return to Nepal. Her family not only welcomed their beloved daughter, her father also purchased a small plot of land for her in Kathmandu that has since grown into the flourishing Dhammakirti Vihara, the nunnery that is her home today and a model for the dozen or so nunneries she has built as vibrant learning centers across Nepal, including in Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha, and most recently in Devadaha, the birthplace of Mahaprajapati. In addition to in-depth dharma education and advanced teacher training for women, Guruma encourages modern education, with many of her students receiving advanced, secular university degrees. Her monastic centers respond to community needs by providing literacy programs for adults and children, libraries, free health care including elder care, food kitchens, and charity outreach for the poor. She’s established a robust publishing enterprise aimed at the lay population, producing over 350 dharma pamphlets and books in vernacular Nepali languages that provide scriptural content from Jatakas to Abhidharma, previously only available in Pali. Undeterred by the Covid-19 lockdown, she initiated online dharma classes taught by young, tech savvy nuns.

Guruma received the precepts of a fully ordained bhikkhuni (nun) in Los Angeles in 1988. She’s traveled worldwide, receiving numerous accolades and awards for her groundbreaking religious and philanthropic work. On her ninetieth birthday, she was celebrated as a national treasure in Nepal, with honors bestowed by the prime minister. In 2024, she was a recipient of the international Outstanding Women in Buddhism Award, which recognizes work toward gender equality and the transformative power of Buddhist practice to change society in beneficial ways.

Today, with thousands of disciples, many of whom are distinguished nuns and teachers in their own right, Guruma remains humble and approachable. Her core message to all audiences is simply that a pure mind leads to a good and happy life. On my return visit, she blesses our pilgrimage group and gestures to the life-sized statue of Mahaprajapati behind her. “May she be your guide and inspiration,” she exhorts us.

Indeed, Guruma, we need look no further than to you as a living example of the liberative power of women in the dharma.

Lynk

Lynk