Hit the road with Jack Kerouac: fine writer, lousy hitchhiker

The Man Who Pays His Way: ‘One of the biggest troubles hitchhiking is having to talk to innumerable people,’ complains the author of ‘On The Road’

Simon Calder, also known as The Man Who Pays His Way, has been writing about travel for The Independent since 1994. In his weekly opinion column, he explores a key travel issue – and what it means for you.

“We gotta go and never stop going till we get there.”

“Where we going, man?”

“I don’t know but we gotta go.”

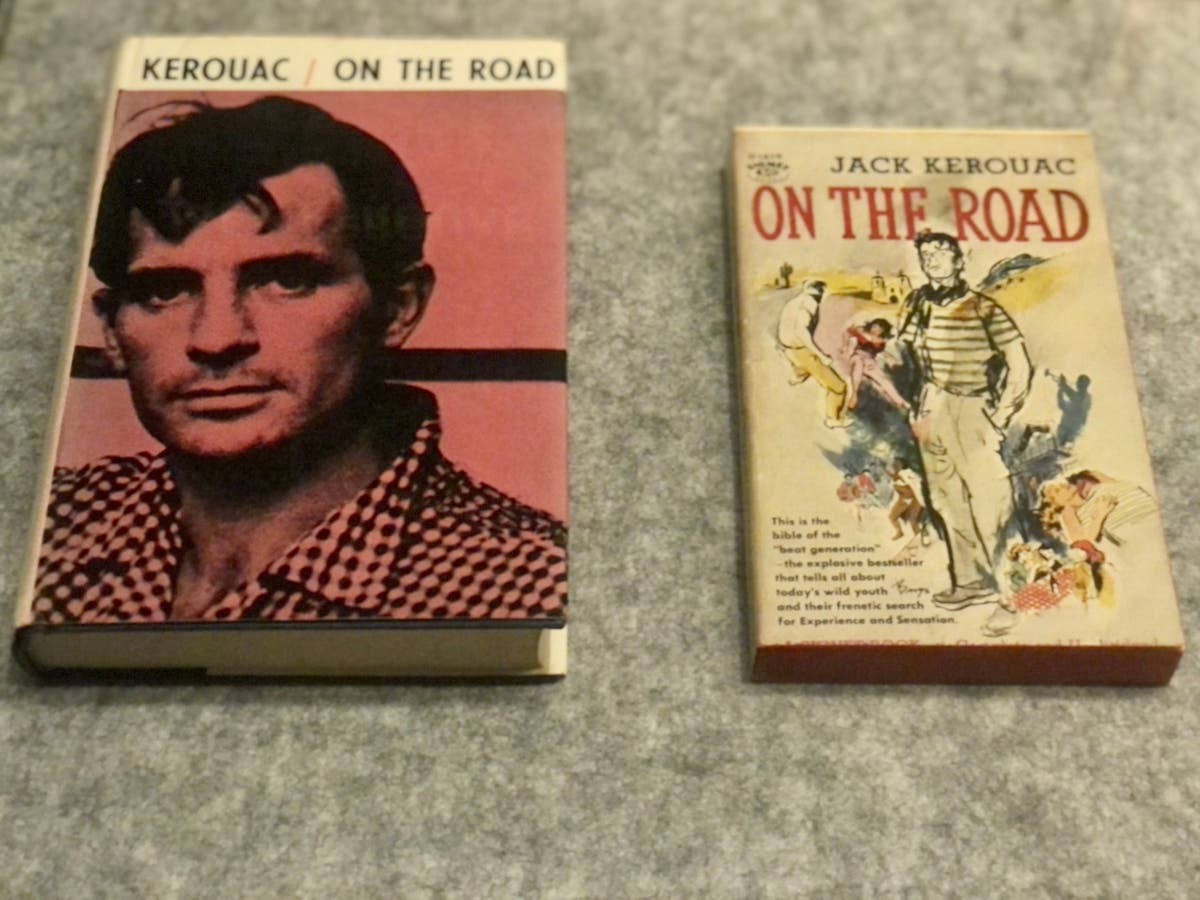

On The Road is one of those books that few people have actually read, but many people think they know. And a good number of those believe it to be a hitchhikers’ bible.

But in the week that marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Jack Kerouac, the truth must be told: the young man who set off from his home town of Lowell, Massachusetts to become a founder member of the Beat Generation was a fine writer, but a lousy hitchhiker.

As Jack’s 1957 highway epic relates, inspiration for his first transcontinental journey came from months of “poring over maps of the United States”.

Jack’s eye was caught by “one long red line called Route 6 that led from the tip of Cape Cod clear to Ely, Nevada, and there dipped down to Los Angeles”.

You can’t fault his ambition: “Now I could see Denver looming ahead of me like the Promised Land, way out there beneath the stars, across the prairie of Iowa and the plains of Nebraska, and I could see the greater vision of San Francisco beyond, like jewels in the night.”

Once Jack actually hit the road, though, the quest to go west from New York City was washed away in a rainstorm on Bear Mountain – just 40 miles from Manhattan.

“I had to ride back to New York in a bus with a delegation of schoolteachers coming back from a weekend in the mountains – chatter-chatter blah-blah, and me swearing for all the time and the money I’d wasted, and telling myself, I wanted to go west and here I’ve been all day and into the night going up and down, north and south, like something that can’t get started.”

Next day, he took the bus as far as Chicago, and eventually made it to California’s most magnetic city, San Francisco, with its “hunger-making raw fog, and the throb of neons in the soft night, the clack of high-heeled beauties, white doves in a Chinese grocery window ... ”

When you get a chance to read On The Road, perhaps during a long journey, you will discover that Jack makes thumbing sound like a chore.

“One of the biggest troubles hitchhiking is having to talk to innumerable people, make them feel that they didn’t make a mistake picking you up, even entertain them almost.”

Surely that is the basic hitchhiking bargain? Some drivers pick up hitchers because they are instinctively kind to fellow humans – but many want to be amused, to be allowed to feel good about being generous, to be kept awake.

“All of which is a great strain,” concludes Jack, “when you’re going all the way and don’t plan to sleep in hotels.”

Perhaps that is why he preferred to be at the wheel himself, cruising at a “steady continental seventy”, even when he and his vagabond pals were out of cash for fuel.

While Jack was driving, the hitchhiking bargain was rather different. Especially after collecting one speeding ticket too many.

“We had fifteen dollars to go all the way,” he reports: “all the way” being a coast-to-coast journey. Even in the cheap old days of the 1940s and 50s, that was way short of the cost of fuel for a 2,500-mile trip.

“We’d have to pick up hitchhikers and bum quarters off them for gas,” he concludes.

Today, no one hitches to or from the town of Lowell; it is a 45-minute suburban train ride from Boston. But it has become a shrine to the patron saint of young adventurers.

Jack Kerouac died tragically young at 47, an alcoholic. But humanity is better for his words.

“I saw God in the sky in the form of huge gold sunburning clouds above the desert that seemed to point a finger at me and say, ‘Pass here and go on, you’re on the road to heaven.’”

JaneWalter

JaneWalter