How I Healed from the Trauma of My Father’s Abandonment

“When another person makes you suffer, it is because he suffers deeply within himself, and his suffering is spilling over. He does not need punishment; he needs help. That’s the message he is sending.” ~Thich Nhat Hanh When I...

“When another person makes you suffer, it is because he suffers deeply within himself, and his suffering is spilling over. He does not need punishment; he needs help. That’s the message he is sending.” ~Thich Nhat Hanh

When I was fifteen years old, my dad abandoned my mother, younger sister, and me after a bankruptcy. My mother sat me down at the kitchen table to show me our financial situation scribbled on a yellow legal pad.

Dad left us with six months of unpaid rent. The landlord threatened us with eviction until mom made a deal to pay extra rent every month to pay off the balance. He agreed to let us live there under those terms.

Dad’s abandonment included disappearing with everything we had of any value. He took our music, art, records—everything that made the place a home. He even took the blender.

My mother’s secretarial job covered our housing, car payment, and other bills, but we would run out of money the last week of the month. I would need to find a way to make up the difference.

My father’s larger-than-life personality made him the center of our universe. With no education, training, or experience, he produced movies, invented a tripod, opened a furniture store, and made a training video for golfers.

Every few months, a new business occupied his passion. The three of us were lightless planets revolving around his flaming sun. After he left, the absence of his gravity left us spinning.

My little sister and I walked the neighborhood looking for babysitting, house cleaning, lawn mowing, and car washing jobs. Nobody has money to pay kids to do odd jobs in poor communities. We each picked up one babysitting job for one night—nothing regular.

One day I answered an ad for a telephone solicitor job a mile and a half from our home. If I made seven sales in two four-hour shifts, they would hire me for a salary plus commission job. At fifteen, I looked thirteen but said I was sixteen.

I made my seventh sale and felt victorious. We were going to be okay. Instead, the manager told me that one of my sales canceled, so I would not get the job. I had worked from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. for two days and didn’t get paid a dime. (I would later learn that the company owners stood trial for profiting from unpaid underage labor).

I walked home crying in the dark. A man in a black car pulled over and offered me a ride. He looked me up and down with a glazed-eyed hunger. I ran across the street and the rest of the way home. The walls of my interior crumbled. I felt my first awareness of the impermanence of all things. I had become a refugee in my hometown.

Our family of three survived the poverty of financial limits. We made it out. However, the deprivation of abandonment cut more deeply.

Abandonment, at any age, leaves one gobsmacked by the cold awareness that someone you love no longer cares if you’re dead or alive. You’ve been rendered irrelevant to someone who once benefited from your loving affection. You feel discarded like yesterday’s trash.

You’re never the same person once you know that someone you love can walk away and not look back. You have eaten from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. It is a knowing that lives in your bones forever. The poverty of an abandoned heart is hard to shake.

Therapists talk about “fear of abandonment” as if it were a form of phobic anxiety, like arachnophobia, the irrational fear of spiders. My mother, sister, and I were not left with a fear of abandonment. We were left abandoned.

When someone is shot with a gun and survives, we don’t tell them they have a “fear of guns.” We call it trauma. The pain lives in the wound. The scars tangible.

Abandonment by someone we love is relational injury, like being shot to pieces but with no visible scars. Neuropsychologists found that losing someone we love activates pain receptors in the brain. It physically hurts. We suffer symptoms akin to opiate withdrawal.

Like opiate recovery, eventually, the pain subsides. New experiences offer us hope for relational healing. We learn to love again. Like a soothing balm over a burn wound, love can ease that pain. The nerve endings calm down. Happiness reappears.

Relational trauma changes the brain. We can experience a thinning in two parts of the brain. One part processes self-awareness (the prefrontal cortex), and the other helps us process and cope with our emotions (the medial temporal lobe). These changes can make us prone to anxiety and depression.

Both of my parents were abandoned by their fathers as toddlers. My father displayed extreme polarities of emotion, manic bursts of enterprising energy, followed by depressed inactivity. My mother periodically experienced depression, followed by long periods of recovery.

Trauma changes us on a cellular level and can linger like a ghost memory for generations. The ghosts of intergenerational suffering haunt many families. If you endure, suffering leads to wisdom. Wisdom leads to the alleviation of suffering.

From suffering we gain: The wisdom of resourcefulness. The confident armor of a survivor. The cellular knowledge that security is an illusion. The ability to bring our own peace to the potluck. The instinct to protect our precious hearts.

I had to attempt new things after each failure on my road to healing. Children are naturally self-centered and feel responsible for the bad things that happen to them. The child believes “If I feel bad, I am bad.” With maturity, we learn to differentiate between what our parents bear responsibility for and our own adult responsibilities. I began to recognize that my father’s decision to leave us had nothing to do with us. He chose to abandon responsibility for his family due to his own failures and weaknesses, not ours.

As I matured emotionally, it became clear that if I wanted a better life I had to make better choices. After several relationships with men who feared commitment and didn’t love me, I made the healthy decision to no longer find that type of man attractive.

Necessity made me a seeker of opportunity. I sought out tools to help me cope. Here’s what I found helpful:

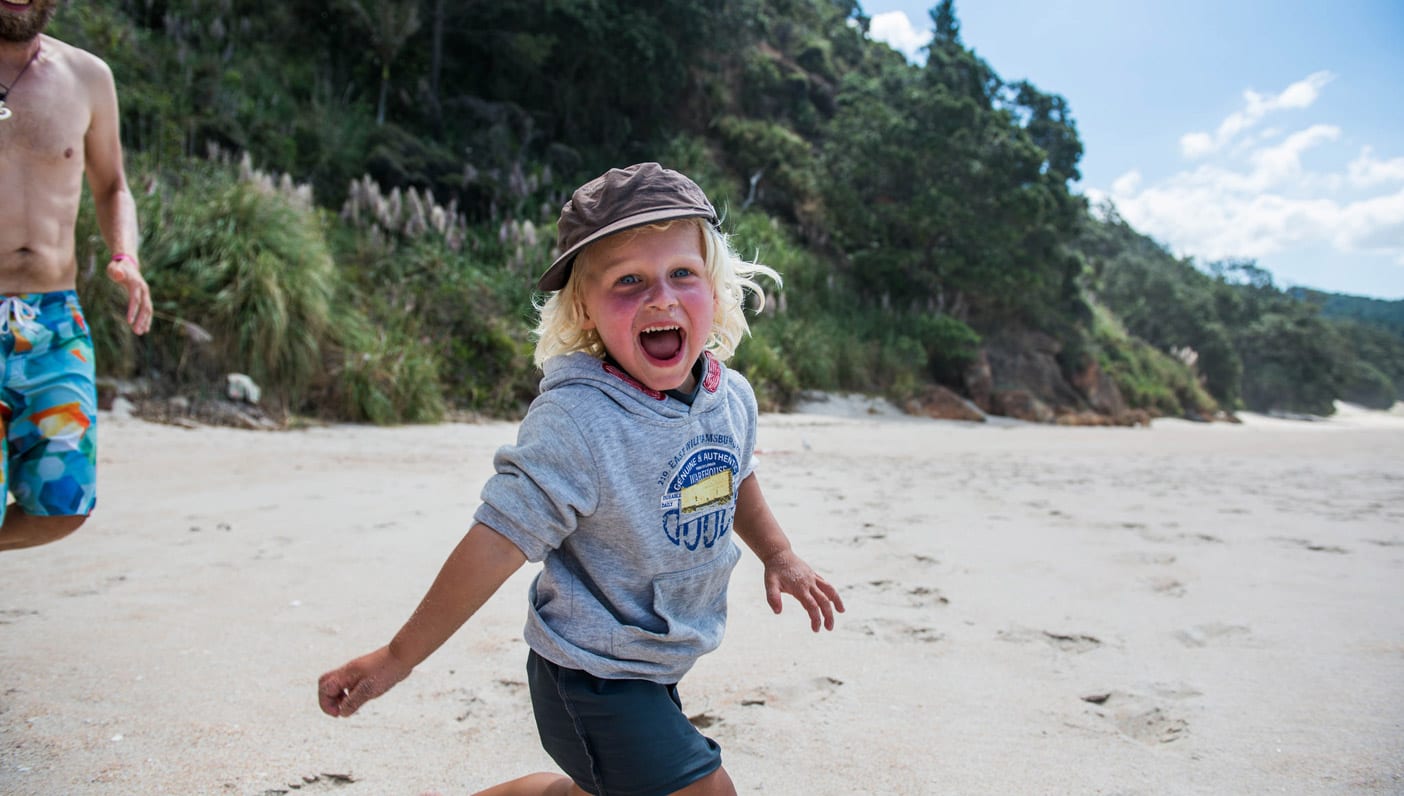

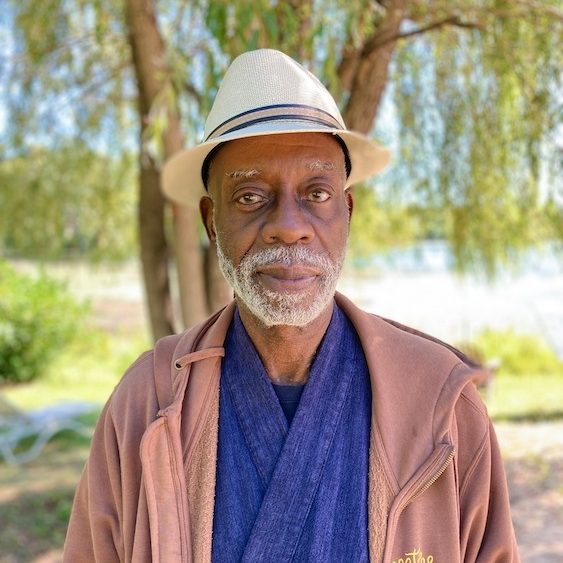

Meditation: At sixteen, I learned how to meditate. I believe that saved me from clinical depression and crippling anxiety. Meditation can repair the damage to the brain stemming from trauma. It provides the experience of non-judging, calm awareness. Friendships: Friendships opened new worlds to me. Friends acted as lateral mentors and taught me how to play guitar, drive, write a resume, and apply to college. Love: Finding loving relationships helped heal the sting of worthlessness. Watching other loving couples served as models for what was possible. Meaning and purpose: Volunteer work, a life of service as a psychotherapist, raising a family, and commitment to a purpose beyond personal ambition increased my happiness and resilience. Compassion: My parents had children at a very young age. They, too, suffered abandonment and loss. I feel compassion for my father’s loss and for what he lost in leaving us. Compassion heals. Gratitude: I’m grateful for my small family and what we built from the rubble. My sister and I raised healthy children who feel secure, having never endured poverty of resources, or abandonment. We broke the transgenerational pattern.Today, when our family gathers, I watch our two grandsons play with their pups in the grassy garden. Their father, our oldest, watches the toddlers with alert protectiveness. My husband gives the boys horsey rides on his back to squeals of delight. Our daughter-in-law prepares a lovely meal with fresh produce from their abundant garden. Our other son performs a funny dance eliciting giggles from his nephews. Our daughter and her husband join in an improvised comedy routine to keep the fun going. We savor the meal as the sun slowly sets.

Love wins.

See a typo or inaccuracy? Please contact us so we can fix it!

Aliver

Aliver