How omicron broke Covid-19 testing

A long line forms outside a Covid-19 mobile testing site offering both rapid and PCR tests in New York City on December 19. | Angus Mordant/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesRapid tests are sold out everywhere, and help might not come...

A surge in cases driven by the highly transmissible omicron variant has stretched America’s Covid-19 testing capabilities to their limit. Rapid antigen tests are out of stock at many drug stores, and lines for PCR tests stretch around the block in cities across the United States. The problem will likely get worse as more people travel for the holidays and fuel new outbreaks, long before new supplies from the federal government are scheduled to arrive.

Covid-19 is spreading so quickly that the US may need between 3 to 5 million tests every day by early February, which is far more than the country currently conducts, according to internal modeling from the Health and Human Services Department. With test supplies dwindling, some local officials are urging the Biden administration to invoke the Defense Production Act, a Korean War-era law that allows the president to order private companies to manufacture certain products during emergencies. To help combat the shortage, the White House said early on Tuesday that it will ship up to 500 million free tests directly to US homes, beginning within the next few weeks.

The supply crunch for tests might seem sudden, but it’s actually been months in the making. Limited federal investment, a sluggish regulatory approval process, and ongoing shortages of raw materials and workers have all hampered test manufacturing. These problems are now playing out as people flock to buy rapid Covid-19 tests before they travel for Christmas and New Year’s, demanding far more tests than the system has available. These tests are also expensive, with the typical cost starting at more than $10.

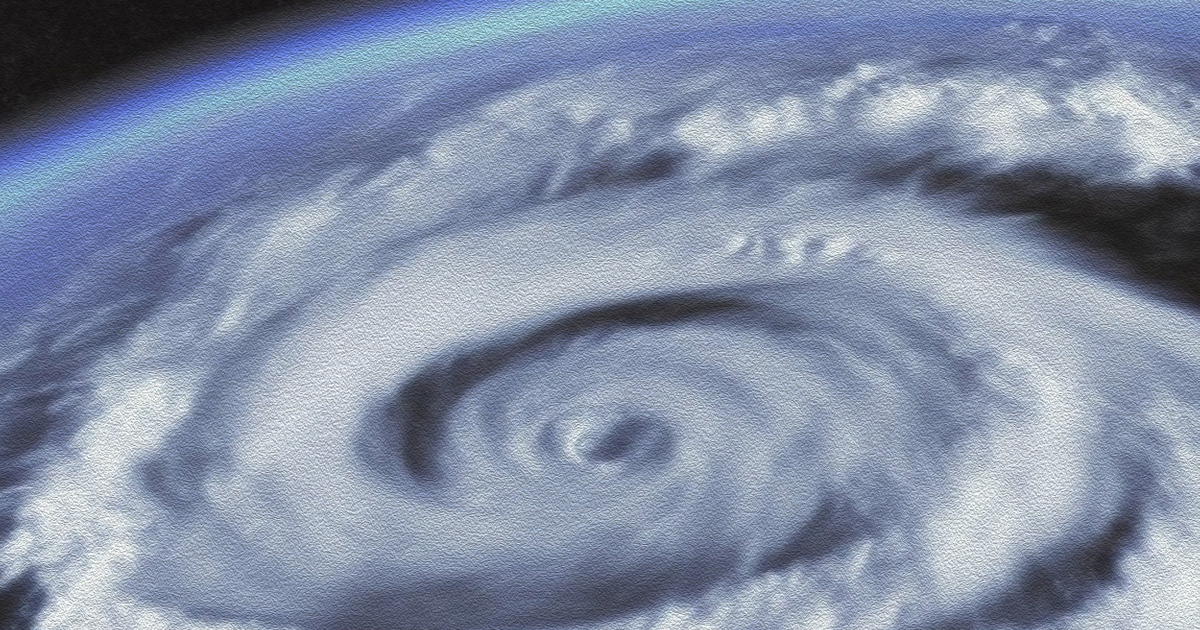

“These factors together created a bit of a perfect storm,” Lindsey Dawson, an associate director of HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told Recode. “Tests are seemingly more difficult to come by than they were even three or four days ago.”

Testing is broken

The gold standard for diagnosing Covid-19 is a PCR test, which involves a health care professional swabbing your nose for a sample that’s then sent to a lab for molecular testing. It typically takes a day for the lab to report results back to patients. These tests are in high demand right now, and wait times for some testing appointments can exceed several hours. Plus, many labs are currently overwhelmed with samples, which has delayed results for several days and rendered them effectively useless.

Ongoing delays for PCR results is one big reason why at-home rapid tests, like BinaxNOW, QuickVue, and Ellume, were supposed to become the main way many people get tested. You can buy these tests over the counter at a pharmacy or order them online. The test kits include a foam swab, a chemical reagent, and a card or cassette. To conduct a test, you swab the inside of your nose to collect a sample, combine that sample with the reagent, and then insert the swab into the card or cassette, which detects the presence of certain proteins called antigens. It only takes about 15 minutes to get a result. While these tests aren’t as accurate as PCR tests, which look for the genetic signature of the virus, they’re a reasonable alternative when PCR tests aren’t available.

There are also several companies now offering at-home molecular test kits, which are about as accurate at PCR tests, but they are not cheap. A company called Detect sells a starter kit with one test and a reusable hub, for around $75, and additional tests are $49 each. Cue Health’s at-home molecular tests are even more expensive. The reusable Cue Reader alone costs $249, and a pack of three tests is $225. There are also at-home PCR tests that use saliva, but these typically require patients to send their samples back to a lab for processing, and cost around $100.

There are a few reasons why these rapid antigen tests are suddenly so scarce. Workplaces and schools bought many of the available rapid tests in bulk earlier this year to speed up their reopening efforts. Resellers, meanwhile, are stockpiling supplies to capitalize on the spread of omicron. And more people are seeking out rapid tests before they travel for the winter holidays, which is whittling down supplies even more.

But the roots of this shortage actually stretch back to the beginning of the pandemic, when the White House prioritized developing vaccines over tests. The Trump administration invested heavily in developing new vaccines through Operation Warp Speed, and the Biden administration’s pandemic strategy has largely focused on distributing those vaccines throughout the country.

At the same time, the Food and Drug Administration has been slow to evaluate and approve over-the-counter rapid tests. These tests were originally categorized as medical devices, which meant they had to meet strict requirements. Two years into the pandemic, only 14 self-administered antigen tests have received an emergency use authorization, according to an Arizona State University database.

Of those tests, Abbott Laboratories’ BinaxNow rapid antigen test accounts for about 75 percent of US retail sales. The dominance of Abbott’s tests has attracted some criticism after ProPublica reported that the director of the FDA’s office for evaluating diagnostic testing, Tim Stenzel, had previously worked at Abbott, as well as Quidel, another company with an approved Covid-19 test. Abbott and Quidel were actually the first two companies that the FDA allowed to mass produce over-the-counter tests, but last month, the agency said it would prioritize approving more rapid tests in order to help ongoing reopening efforts and to prepare the country for the upcoming holidays.

Test manufacturing also lost momentum as vaccinations curbed infection rates over the summer. Venues began to require proof of vaccination for entry, and the CDC declared that vaccinated people did not need to be regularly tested. Sensing that Covid-19 tests would no longer be a hot commodity, makers of popular rapid tests prepared to scale down their manufacturing. These companies are now racing to shift back into gear.

“I can tell you that we’re seeing unprecedented demand for BinaxNOW and we’re sending them out as fast as we can make them,” John Koval, Abbott’s director of public affairs for rapid diagnostics, told Recode. “Despite public health guidance over the summer that caused the market for rapid testing to plummet, we never stopped making tests.”

Quickly boosting manufacturing levels isn’t so easy, though. Ellume, an Australian company that produces Covid-19 rapid tests, said in September that demand was already 1,000 times what it had originally predicted. Test makers haven’t been immune from the global supply chain crisis, either. Shortages of foam swabs, machinery, electronics, and specialty paper for test cards have all slowed down test manufacturing.

The labor shortage has been a challenge, too. Orasure, which makes a rapid test called InteliSwab, has not been able to hire enough people at its Pennsylvania plant to meet demand. And BD, which sells an at-home test called Veritor, warned in its annual notice to investors in November that ongoing supply chain issues, including transportation problems and component availability, could hurt its entire business.

Fixes are coming — slowly

This fall, the Biden administration launched a more aggressive testing strategy. The White House spent a combined $3 billion to boost manufacturing of rapid tests. The Biden administration also directed insurance companies to cover the cost of over-the-counter rapid tests, though that guidance may not arrive until January 15 and won’t apply retroactively. The policy also doesn’t help people without private insurance. The Health and Human Services Department said in October that it would spend $70 million to help bring more tests onto the US market, with an eye toward tests that can be manufactured at scale.

The US government’s approach stands in stark contrast to policies abroad. In the United Kingdom, for instance, Covid-19 tests are distributed for free, and the government mails kits to people’s homes if they’re not able to get a test through school or work. Germany made Covid-19 tests free between March and October.

Still, the White House says that the country is “on track to quadruple the supply of rapid at-home tests that we had in late summer.” That seems ambitious. Ellume, the Australian test maker, was only scheduled to start production at a new manufacturing plant in Maryland this month. That company plans to produce 70 million tests a month by the end of December, including tests ordered by the federal government. Abbott says it should meet that same target by January. And iHealth Labs, which received an emergency use authorization for its over-the-counter test just last month, says it could manufacture 200 million tests a month starting next year.

But the number of people testing positive is growing by the day, which means the number of people exposed to Covid-19 who need to be tested is growing, too. Right now, it’s not clear whether we have enough tests in the right places and at the right time to clamp down on the spread of Covid-19 overall. After all, if we had enough rapid tests, people could regularly test themselves, allowing us to quickly catch new cases and slow the spread of the virus.

In the meantime…

Expect shortages. Both Walgreens and CVS told Recode that demand for tests is far outpacing supply, and that some of their drug stores will be out of stock. Instead of visiting several stores in person, you can check to see if tests are in stock on many pharmacies’ websites, though they may not always be up to date. Keep in mind that you may be subject to inventory limits. Walgreens is currently only allowing customers to purchase four Covid-19 testing products at a time. In any case, if you need an at-home test, you should buy the first one you see.

There are also social media accounts and local news sites tracking the availability of tests throughout different neighborhoods, and people may be sharing information on community Facebook groups and Nextdoor pages. You should also keep an eye on buying guides, like this one from Wired, with updated links to places selling tests online. While you look for supplies, keep an eye out for scammers impersonating government offices and demanding money for tests upfront.

Even if you come up short shopping for rapid tests, you might be able to secure a PCR test at a local pharmacy, urgent care clinic, or mobile testing center. Some of these facilities may also offer rapid tests, so you should ask about getting both a PCR and a rapid test when you go.

In the weeks to come, more options for free tests should become available, too. The Biden administration has distributed many of the rapid tests it purchased to community centers and clinics, which may be distributing tests for free. The White House plans to create a new website, which people can use to request the federal government’s free at-home tests. Local governments may also be giving out tests.

Still, it may not be possible to find a test. If you think you have Covid-19, you should isolate, and if necessary, see what treatments might be available. But it may not be possible to know for sure. That means, unfortunately, that now’s as good a time as any to get used to pandemic uncertainty.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

AbJimroe

AbJimroe

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=6e07dc5773&c=1)