How to Become a Thought Leader in Just 6 Incredibly Difficult Steps

I am a thought leader. I feel gross for typing those words. But here’s something that feels less gross to type: over the past decade, I have been lucky to find a small-but-important group of people who give a...

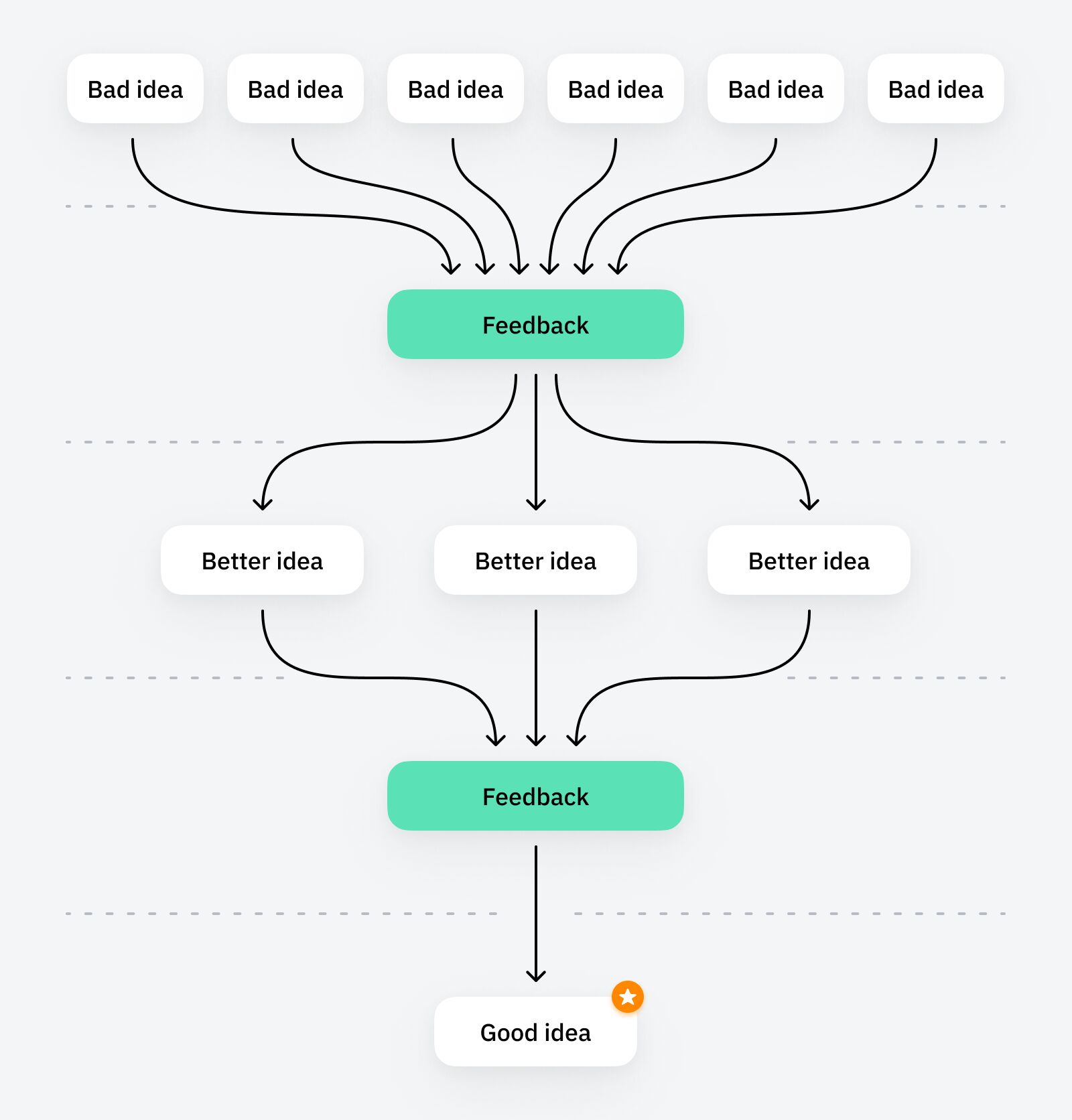

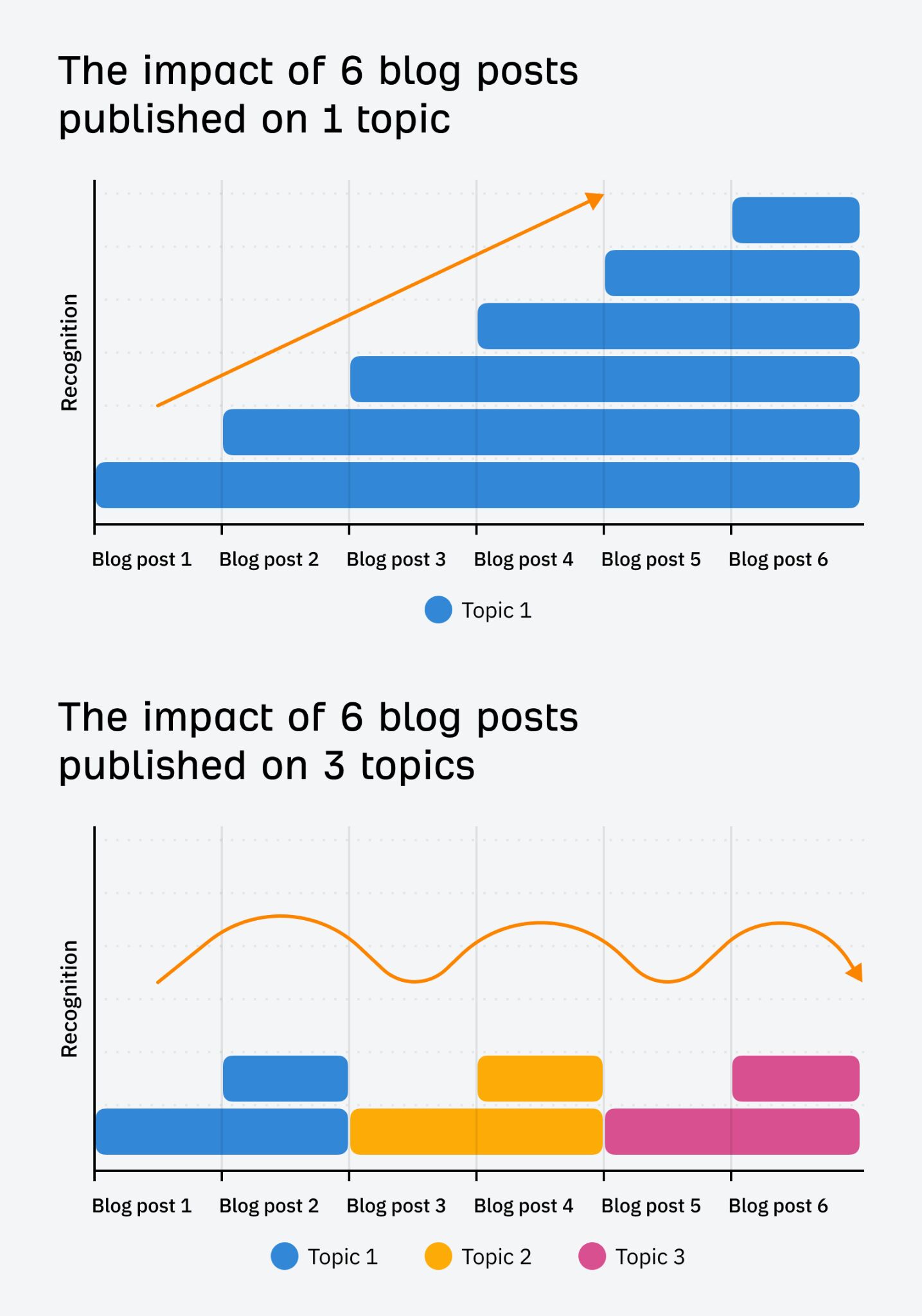

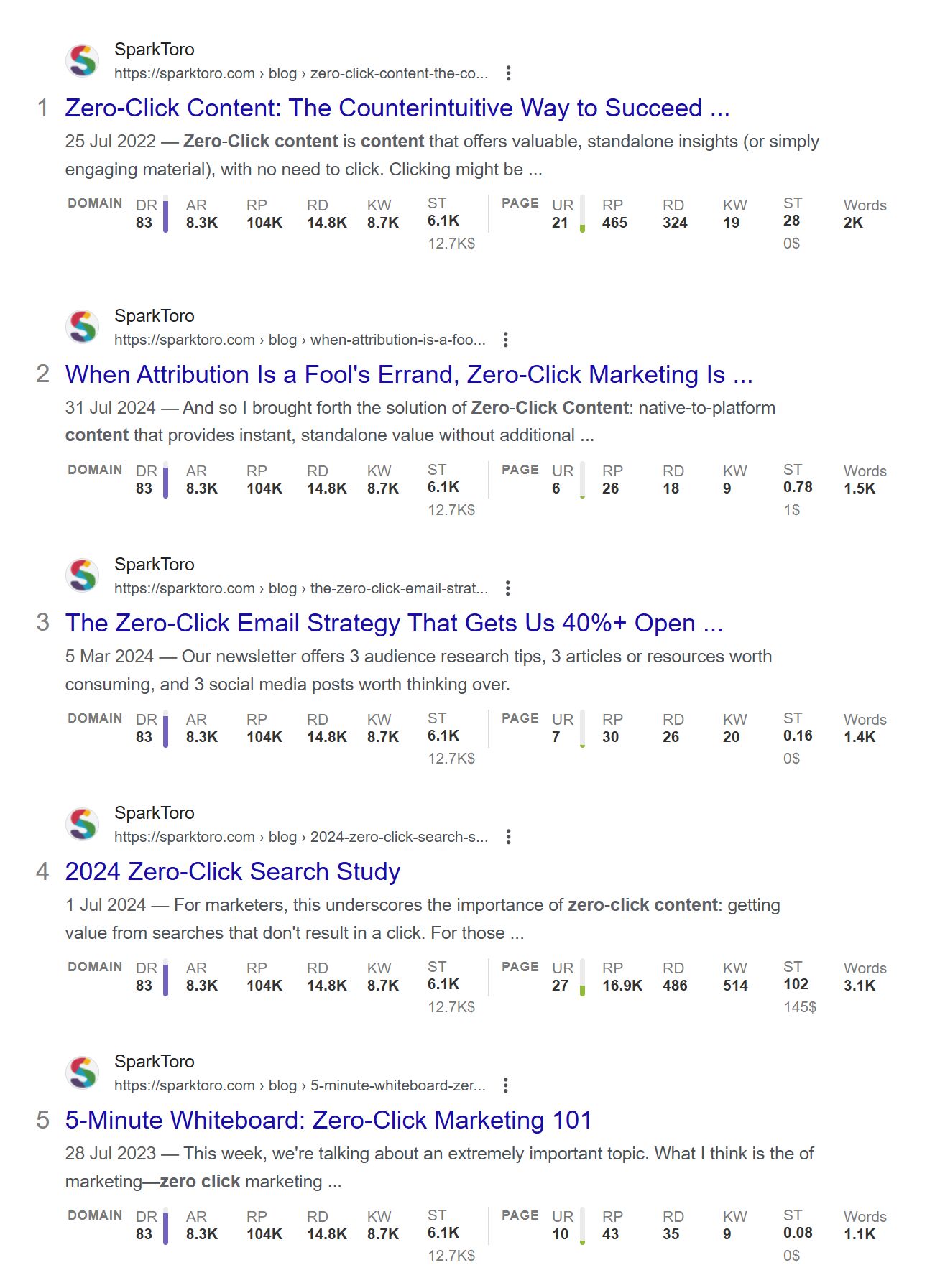

I’m going to type the lamest thing I’ve ever typed and make 90% of you close the page right now. Are you ready? I am a thought leader. I feel gross for typing those words. But here’s something that feels less gross to type: over the past decade, I have been lucky to find a small-but-important group of people who give a damn about my ideas. This has been beneficial for my career, and beneficial for the companies I join. I’ve seen my ideas referenced on stage, linked to in industry publications, debated on social media. I get invited to apply for amazing jobs, to speak at conferences and appear on podcasts. Yada yada yada, you get the idea. So why am I sharing this? To tell you how amazing I am? No—the opposite. I have an inside view of just how unremarkable I am. I have sat at my desk writing blog posts for fourteen years. I have saved no lives, climbed no mountains. This is great news. If someone as unremarkable as me can do this, so can you. Whatever I have done to confer these benefits, I guarantee that you can do too. So let’s explore how you can become a thought leader. Publishing tons is the necessary first condition for becoming a thought leader. You can’t change anyone’s perspective with clever ideas that never leave your head. Many of the smartest, most innovative people I know self-limit because of a reticence to actually publish, and put stuff out into the world. Sit and wait for the perfect idea to emerge before publishing, and you’ll wait forever. It’s almost impossible to tell which ideas are useful, interesting, or resonant, without just putting a ton of stuff out there and learning from the response. The first step towards becoming a thought leader is to make a bunch of stuff. The goal is to develop tons of rapid feedback loops, gradually transforming bad ideas into better ones into good ones through continued iteration and real-world feedback. Thought leadership is, ironically, less about clever intellectual thought and more about the continued action of publishing, refining, and publishing again. Post on social, send that weekly Substack, blog wherever people will let you blog, publish a daily YouTube short. Ship, ship, ship. Many people publish prolifically without becoming a thought leader. It’s possible to rack up millions of social media impressions each month without ever changing anyone’s mind, challenging the audience’s beliefs, or improving how they tackle life’s problems. I see plenty of these rehashed truisms as I doomscroll my LinkedIn feed at 11pm (why do I do that to myself?), but I forget them—and the people who created them—as soon as they leave my eyeline. Publishing prolifically is necessary but not sufficient for becoming a thought leader. You have to also share things that are useful, and surprising, and original. By definition, thought leadership exists at the fringes of common knowledge. You can’t share things that everyone knows. My former colleague Katie Parrott called these ideas “earned secrets”, and I love this definition. As the phrase’s originator, Ben Horowitz, explains: “You did something in your past to solve a hard problem and learned something about the world that not a lot of other people know.” To repeat a lesson from above, thought leadership is less about thinking and more about doing. Work hard, tackle difficult problems, and share the lessons you learn on the way. You can’t wrest your way into thought leadership through a sheer act of intellectual will. It is not a problem to be solved by writing; you have to do hard things. Many of the smartest, most innovative people I’ve known are also the most reluctant to be pigeonholed and commit to a single topic. But the more diffuse the focus of your ideas and content creation, the harder it is for other people to intuitively understand what you’re about, and why they should care about you. People know me for one thing: content marketing. I dip into and out of related topics—writing, research, SEO, marketing—but the body of my work has always been on the sole topic of content marketing. This has two huge benefits. It’s very easy for people to understand my value proposition in a heartbeat: I share ideas about content marketing. If you care about content marketing, I might be worth engaging with. More importantly, every single thing I’ve published, recorded, said or done in the past fourteen years has compounded. All of my old ideas, articles, talks, and podcasts are still relevant to people who care about my current ideas. I can call upon a decade of thought, experience, and research every time I want to share something new. The more specific your topic of choice, the easier it is to become a thought leader. It’s easier to share novel ideas about programmatic search than it is about the broader topic of content marketing, or marketing, or business. The bigger the topic, the more established ideas and noise you’ll encounter, and the harder it is to be original. In the beginning, you’re a nobody. Even if you share great ideas, there’s a high chance they’ll never make it through the audience’s credibility filter, the heuristic we all use to judge whether an idea is even worth pausing to consider: does it come from a credible source? We’re all inundated by so much noise every day that we have to ignore 99% of it simply to function. As an unknown person, you need to find a way to signal to the reader that yes, these ideas are worth paying attention to. Being prolific and building familiarity with your name and topic of choice can, over time, afford you this credibility. But it’s also helpful to speed things along by borrowing the credibility of established figures and brands. I borrowed the credibility of Animalz and Jimmy Daly when I first started writing. Jimmy was already known for sharing smart, original ideas about content marketing; when I published on his blog, or appeared on his podcast, I became more credible by proxy (thanks Jimmy). Now, I work at Ahrefs, alongside many, many people smarter and better known than me (Tim, Patrick, Sam…). I borrow their credibility every time I publish, every time I share my byline. A post by “Ryan from Ahrefs” carries significance because of the hard work put into building Ahrefs the brand for the past decade. I stand on the shoulders of giants. Ahrefs is well-regarded; I inherent some small portion of those good vibes when I’m implicitly or explicitly associated with the brand. (Or put another way—this borrowed credibility allows me to escape the default blocklist.) There is a real benefit to joining companies that are already well-regarded in your industry. If that’s not possible, you can publish in well-known publications, seek feedback or quotes from well-known people in your content, or build a network of similarly aspiring thought leaders and allow your slow, incremental gains in credibility to rub off on each other. For people to share your ideas with others or reference them in talks, they need to be memorable, capable of lodging in the recipient’s brain amidst tons of competition. We have more control over “being memorable” than we might think. Thought leaders have a knack for distilling their ideas into their smallest, most memorable form: a single catchphrase that encapsulates the key points. The skyscraper technique. Invisible asymptotes. Zero-click content. Goog enough. Spiky point of view. I call these neologisms “coined concepts”. These phrases are vivid and easy to remember, but more importantly, they’re easy to share with others, communicating their core ideas in a few short words. They pique the reader’s interest, turn your nascent ideas into some that feels concrete, and make people look good when they reference these clever, professional-sounding frameworks in their own work. They create distribution incentives for your ideas. 90% of your attempts to coin a concept won’t stick, but the 10% that do, really do. The goal is to get your reps in and give everything a name: gonzo content, copycat content, the default blocklist, the era of information abundance, content arbitrage, the search singularity… Great ideas are eye-wateringly hard to find, so when you do find one, milk it dry. This is something that lots of people (myself included) find very hard. It’s usually more exciting to move on to new ideas and new topics instead of endlessly promoting the same idea. But the internet is noisy. Most social posts, webinars, podcasts, and articles have a surprisingly short half-life. Most ideas, even the great ones, fade into obscurity in a matter of days… unless you deliberately and continuously repromote them. Amanda Natividad from SparkToro wrote a killer post about zero-click content. But perhaps more important than the initial idea was her ability to take that great idea on tour, creating dozens of opportunities to reference and build on the idea for months afterward. This is what happens when you run a site: search on SparkToro for “zero-click content”: Three blog posts, one data study, one video—all anchored in the idea of “zero-click content”. And this is just on-site content, not including social media posts, podcast and webinar appearances, SparkToro’s own events, references in guest posts… Here comes the final, most important step to becoming a thought leader: you need to write “thought leader” in your LinkedIn bio. Obviously, I’m joking, and you would never do that (right?). But this belies a serious point. “Thought leadership” is a cringe-inducing topic with a serious branding problem. I found it genuinely difficult to start this article with a claim of being a thought leader. To claim you have “leading thoughts” is the highest order of narcissism. Even if the epithet was accurate, who would I be to claim it for myself? Being a “thought leader” is a status that is conferred by other people. It describes things we all want. When you say something, people listen. When you ask for something, people help. When you sell something, people buy. But to try and become a thought leader is to become the ouroboros eating its own tail. You can’t confer the status upon yourself, and you can’t earn the status by trying to get the status. Thought leaders are people who immerse themselves in the hardest problems of their industry, and then spend lots of energy sharing the results with other people. They do hard things because they enjoy them, and they share their experiences because it makes them happy to talk about them. In most cases, “becoming a thought leader” is the furthest thing from their minds. Thought leaders—at least, the ones worth following—are big nerds who can’t help but share the nerdy stuff they’re working on. That provides a clear path for us all to follow: to become a thought leader, you need to spend less time thinking, more time doing. One of the smartest people I know, Bernard Huang, referencing something I wrote on stage at Ahrefs Evolve. I giggled like a school kid when this happened.

One of the smartest people I know, Bernard Huang, referencing something I wrote on stage at Ahrefs Evolve. I giggled like a school kid when this happened.

Here’s a way of visualising this idea: spread your content across too many unrelated topics, and you arrest the “compounding” effect that comes from covering one topic for a long time.

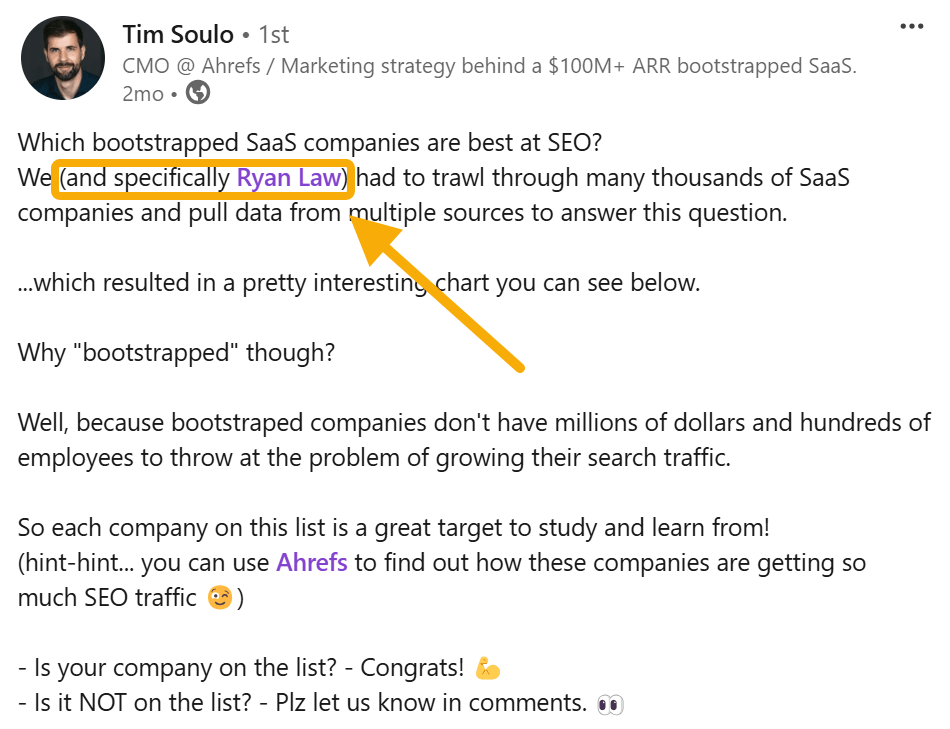

Here’s a way of visualising this idea: spread your content across too many unrelated topics, and you arrest the “compounding” effect that comes from covering one topic for a long time. Every reshare from someone more accomplished and better known than me is a metaphorical stamp of approval. (Thanks Tim!)

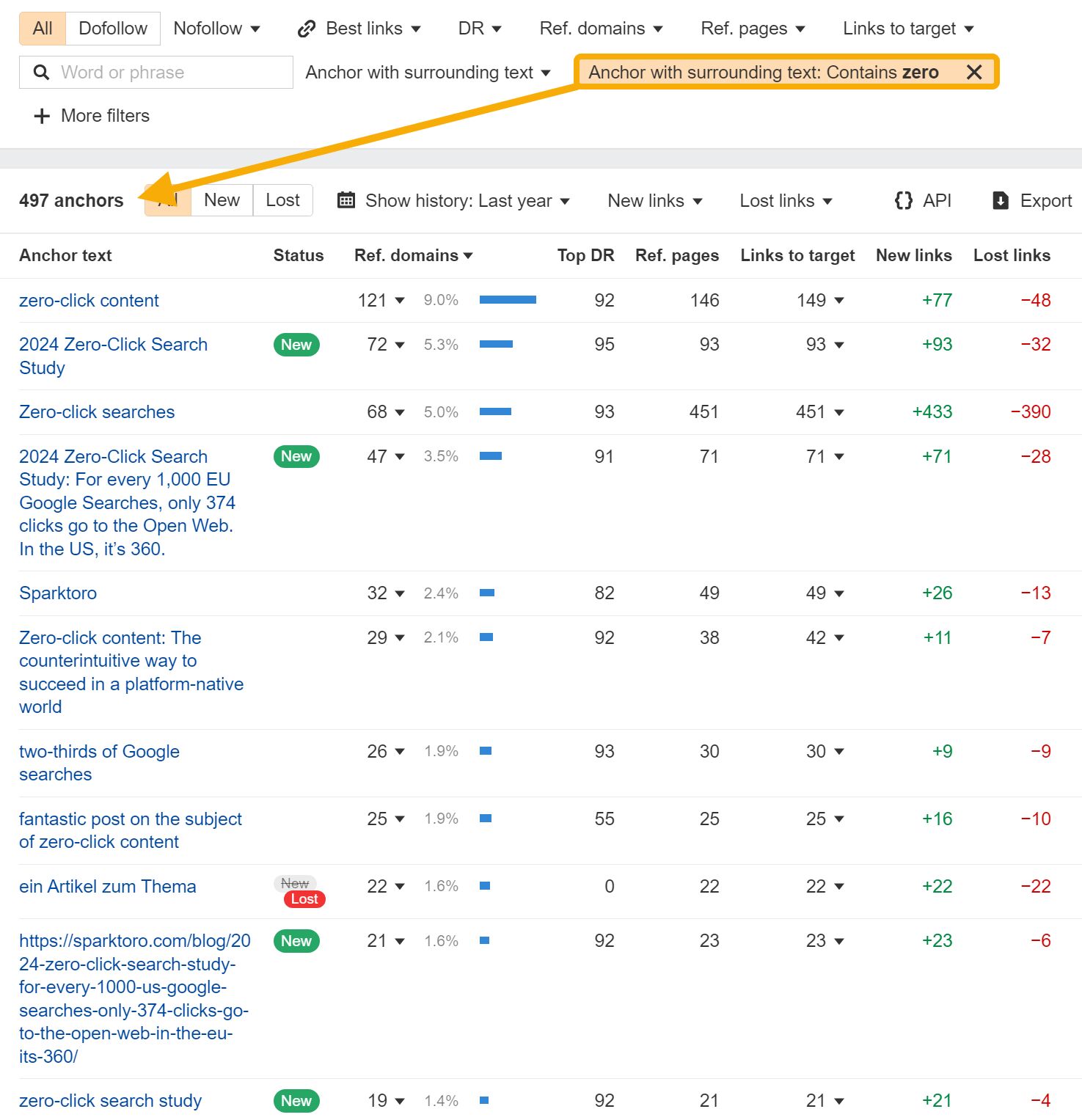

Every reshare from someone more accomplished and better known than me is a metaphorical stamp of approval. (Thanks Tim!) Almost 500 of SparkToro’s backlinks reference “zero-click content”—a great example of a coined concept—in their anchor text.

Almost 500 of SparkToro’s backlinks reference “zero-click content”—a great example of a coined concept—in their anchor text.

Final thoughts

Tywin Lannister had the right idea in this (slightly altered) Game of Thrones quote.

Tywin Lannister had the right idea in this (slightly altered) Game of Thrones quote.

Tfoso

Tfoso