Making All of Life a Field of Awakening

The story behind Eihei Dogen’s legendary “Genjokoan” The post Making All of Life a Field of Awakening appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

For Soto Zen practitioners, “Genjokoan” has become one of Dogen’s most beloved and chanted texts because of its poetic language and deep reflection on the nature of actualizing the buddhadharma. It is part of a larger work, Shobogenzo (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye), a collection of essays that he wrote and continued to revise throughout his life. Shobogenzo is considered his masterwork.

There are multiple compilations of Shobogenzo, but Dogen personally arranged the chapters in three of them: the sixty-chapter, seventy-five-chapter, and twelve-chapter versions. In both the sixty- and twelve-chapter compilations, “Genjokoan” is placed first. Later versions of Shobogenzo, compiled by others, arrange Dogen’s essays in chronological order of composition, resulting in “Genjokoan” usually occupying the third position.

Since Dogen always placed “Genjokoan” as the opening chapter in the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, we must assume that he felt it to be a crucial and comprehensive introduction to his teachings. Dogen’s disciple Senne writes, “The word genjokoan can be used together with any term. . . . [Therefore] the title of each of the seventy-five chapters of this writing can be called genjo-koan.” Senne explains why this is so in his definition of the word genjo. He defines gen as “manifestation”; and jo, he explains as “this jo of genjo (成, to become) as jo in jobutsu (to become a buddha).” In other words, every fascicle of the Treasury of the True Dharma Eye is a primer on manifesting buddha-nature through bodhisattva practice.

Dogen’s Encounter with the Tenzo: Practice-Realization in Everyday Life

Dogen began writing “Genjokoan” after returning from China, where he awakened under the tutelage of his master Rujing. It is a common tenet in the Soto school that he went to China to answer a question that had plagued him. This question was recorded in The Record of Kenzei, published in 1422: “If all sentient beings possess the buddha-nature and Tathagata exists without change [as enunciated in the Nirvana Sutra], then why must people develop the aspiration for awakening and vigorously engage in austerities in order to realize this truth?”

As Dogen scholar Steven Heine points out, Dogen posits the same question in the opening lines of “Fukanzazengi”:

Fundamentally, the basis of the Way is thoroughly pervasive, so how could it be contingent on practice and realization? The vehicle of the ancestors is naturally unrestricted, then why should we expend sustained effort?

Thomas Kasulis, a scholar of Japanese religion, asserts that this transformative query became the basis of Dogen’s mature understanding. How Kenzei phrased this question may not be historically accurate, but its presentation in “Fukanzazengi” indicates that Dogen believed the basis of this question needed answering.

Dogen was about 23 years old when he went to China. I imagine Dogen, at that time, to be a person who tended to distill his religious experiences into intellectual paradigms. Perhaps he was a little arrogant but nonetheless a sincere and curious practitioner. He clearly trusted his own gut about what constituted authentic practice and realization. This is not surprising because he had been practicing Buddhism since he was ordained at thirteen, and by the time he went to China in 1223, he had been practicing continuously for ten years. Yet Dogen clearly had not found what he felt was authentically Buddha’s Way and was searching for answers in China.

In “Tenzo Kyokun” (Instructions for the Cook), Dogen relates that his first dharma encounter upon arriving in China was with the 61-year-old tenzo of Mount Ayuwang monastery, who visited Dogen’s ship harbored in Qingyuan. When the tenzo prepares to leave after their visit, Dogen encourages him to stay and talk more about the dharma rather than returning to his duties at the monastery. The tenzo declines, saying that it is his responsibility to oversee the meals. Puzzled, Dogen asks why a person of his rank could not leave the preparation of the meals to his staff. When the tenzo replies that it is his practice to be there and his responsibility to be accountable, Dogen is still reluctant to accept this as a valid reason for not staying to continue their conversation about the dharma. After all, talking about the dharma is surely more interesting and important than returning to the mundane task of preparing meals for the monastics.

As their discussion continues, Dogen asks,

“Venerable tenzo, in your advanced years, why do you not wholeheartedly engage the Way through zazen or penetrate the words and stories of the ancient masters, instead of troubling yourself by being tenzo and just working? What is that good for?”

The tenzo laughed loudly and said, “Oh, good fellow from a foreign country, you have not yet understood wholeheartedly engaging in the Way, and you do not yet know what words and phrases are.”

Hearing this, I suddenly felt ashamed and stunned, and then asked him, “What are words and phrases? What is wholeheartedly engaging the Way?”

The tenzo said, “If you do not stumble over this question, you are really a true person.” [Dogen comments], I could not understand at the time.

Reading Dogen’s version of this initial encounter with the older monk, whom he would meet again later, we can glean a few things about his understanding and personality at that time. It underscores the young Dogen’s attachment to studying ancestral practice and his belief in zazen as the singular activity of practice. It also clearly indicates his curiosity and humility, for he was not defensive when the older monk laughed at him.

Most importantly, this encounter sparked within Dogen a curiosity about the true nature of practice as presented by the tenzo. The monk’s admonitions that “you do not yet know what words and phrases are” and “you have not yet understood wholeheartedly engaging in the Way” point out Dogen’s basic misunderstanding. At that time, Dogen put more credence in studying the words of the buddhas and ancestors and in engaging in formal sitting than he did in actualizing practice through his daily activity. He thought intellectual study, formal zazen, and talking about practice were sufficient. According to Kasulis, Dogen’s previous practice as a Tendai monk would have mostly involved formal debates, “complex esoteric Buddhist ritual(s)” consisting of a “plethora of mantras, mudras, mandalas” as well as sutra chanting and hours of “Tendai-style tranquil meditation.” None of these activities are grounded in enacting practice in daily life. The tenzo’s comments were an attempt to bring forth this deficiency in Dogen’s understanding.

When I was a senior student at San Francisco Zen Center, a student who was leaving City Center came to me informally for advice. He asked how he could continue his practice without the formal trappings of temple life. How, he wondered, could he practice in daily life without a zendo for sitting, group chanting service, and the daily schedule of a residential Zen center? I understood that for him, practice was only the formal training regime of Soto Zen, and those practices did not extend to the day-to-day tasks of daily life. This appears to have been Dogen’s understanding as well, at the time of his conversation with the tenzo.

Indeed, many of us come to practice thinking that our daily life is inferior to Buddhist practice. We understand that nirvana is something outside of our life, some place pure and without problems. If we study Dogen with this model, we will have a hard time grasping his understanding. Studying the Buddha’s Way and applying those teachings to our mundane life are not different. We are not trying to transcend our life.

Studying the Buddha’s Way and applying those teachings to our mundane life are not different. We are not trying to transcend our life.

When Dogen continued his dialogue with the monk a few months later, he asked about “words and phrases” and practice.

Dogen relays the dialogue:

[The (now retired) tenzo said], “People who study words and phrases should know the significance of words and phrases. People dedicated to wholehearted practice need to affirm the significance of engaging the Way.”

I asked him, “What are words and phrases?”

The tenzo said, “One, two, three, four, five.”

Also I asked him, “What is wholeheartedly engaging the Way?”

The tenzo said, “In the whole world it is never hidden.”

This fateful encounter with the tenzo opened Dogen’s eyes to engaging with the totality of his life as practice. These “words and phrases” are not empty platitudes, intellectual instructions, or puzzles but rather dharma gates to seeing the buddhadharma as our daily life. One might reword the tenzo’s final teaching in that exchange as, “In the whole world practice-realization is never hidden.” It is right where we are.

Dogen praises this conversation with the tenzo as transformative. Then he continues his analysis of the tenzo’s teaching with the following insight:

What I previously saw of words and phrases is one, two, three, four, five. Today what I see of words and phrases is also six, seven, eight, nine, ten. My junior fellow-practitioners, completely see this [concrete particular phenomena] in that [universal interdependence], completely see that [universal interdependence] in this [concrete particular phenomena]. Making such an effort you can totally grasp one-flavor Zen through words and phrases.

In other words, we cannot separate the day-to-day activities and encounters of our life from what we may perceive as something beyond daily life. They are intertwined, interdependent, and cannot be separated.

If we look back at Dogen’s dilemma as presented in The Record of Kenzei—“If all sentient beings possess the buddha-nature . . . then why must people develop the aspiration for awakening and vigorously engage in austerities in order to realize this truth?”—we can see that his conversations with the tenzo were a pivotal event in his development. The opening lines of “Fukanzazengi,” which Dogen presents as a question, can now be read as a statement:

Fundamentally, the basis of the Way is thoroughly pervasive, enacting it [genjokoan “manifesting suchness”] . . . is contingent on practice-realization [verification]. The vehicle of the ancestors is naturally unrestricted, [therefore] we should expend sustained effort.

Dogen realized that practicing the dharma is manifesting and verifying reality’s functioning. Such manifestation only comes forth when practice is grounded in and reflective of all of our activity—not just formal practice. Our concrete and particular lives are not different from what is universal and codependent.

Our concrete and particular lives are not different from what is universal and codependent.

Although Dogen’s “Fukanzazengi” encourages and instructs practitioners to make seated meditation a primary focus of practice, he comments, “If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, you are thereby negotiating the Way with your practice-realization undefiled. As you proceed along the Way, you will attain a state of everydayness.” In other words, this zazen mind must be carried over into one’s daily life.

If formal zazen is the most important message of Dogen’s teaching, as many Soto Zen practitioners in the United States now believe, then why did Dogen place “Genjokoan,” which does not specifically mention zazen at any point, as the first teaching in Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, instead of “Fukanzazengi”? Dogen never stopped advocating for the importance of zazen as an expression of our realization and as a practice that manifests and supports awakening. But he also taught that the whole of our activity should be a field of awakening. This was the heart of the tenzo’s teaching: Our awakened life is manifest in daily life. From this perspective, “Genjokoan” describes how a mature practitioner manifests reality’s function in all their actions and interactions with others. Genjokoan is the ground, the path, and the mature enactment of the bodhisattva vow.

Realization Is Perception

“Genjokoan,” like all of Dogen’s teachings, is tactile—pertaining to the very stuff of our life. Practice manifests as we engage with people, things, weather, the earth, and so on through our senses. Realization itself manifests through form.

When we study the meaning of no-self, or no-inherently-existing-self, we may think that the goal of this practice is to annihilate the self. In perhaps a subtler way, we imagine that practice-realization (or verification) happens outside the self or outside the self that experiences itself. Or it is not the self of our ordinary life. Not our bodily self. We assume that our ordinary mind is delusional and that a mind unclouded by delusion is outside of our ordinary state. We think practice is enacted by a special person who is without personality or problems. Perhaps we think that the problem is that we think or experience our life through the self. Of course, this begs the question: Who else would practice and respond skillfully other than this particular person—this self?

Hee-Jin Kim writes, “If the cause for the arising of our predicament lies within discrimination, then the cause for the eradication of such a predicament also lies within that discrimination itself, not outside.” Discrimination or perceptions happen within the purview of each person’s mind and senses. Kim comments a few sentences later,

Yet, discriminative activities, once freed of substantialist, egocentric obsessions, can function compassionately and creatively. Thus there are two kinds of discriminative thinking at an existential level, delusive and enlightened. To Dogen, whether or not we use discrimination in the Zen salvific project is not the issue; rather, how we use it is.

Our mental discriminations are based upon the activity of our five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Our mental-emotional understanding, which is based upon our interpretation of incoming sensory awareness, can either selfishly override the totality of our experience with other beings or we can align ourselves with others and, in concert with self and other, respond skillfully, thus manifesting our buddha-nature.

Perhaps Dogen’s most famous statement on this topic comes in “Genjokoan”:

To study the Buddha Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be verified by all things. To be verified by all things is to let the body and mind of the self and the body and mind of others drop off. There is a trace of realization that cannot be grasped. We endlessly express this ungraspable trace of realization.

Although you may have read or heard this teaching many times, let’s pause and consider the question of “self” as the locus of awakening. Who is it that “studies the self”? Who is it that “forgets the self”? Who or what is “verified by all things”? And what is “dropped off”? Furthermore, who or what “express[es] this ungraspable trace of realization”? Earlier in “Genjokoan,” Dogen writes, “All things coming and carrying out practice-enlightenment through the self is realization.” “Through the self” indicates that our practice is manifest by this body and mind—not another. It is the self’s activity, in concert with all being(s)’ activity throughout time and space, in this body, with this mind, that engages practice-realization.

Throughout “Genjokoan,” Dogen directly or metaphorically refers to our experiential sensations and perceptions. He writes about seeing flowers fall and weeds grow. He observes how we carry ourselves toward things or we meet the other. When we see color and hear sounds, we may awaken. And we experience darkness and illumination. All the senses are activated: touch, perception, hearing, seeing, and even smell and taste—if we use our imagination.

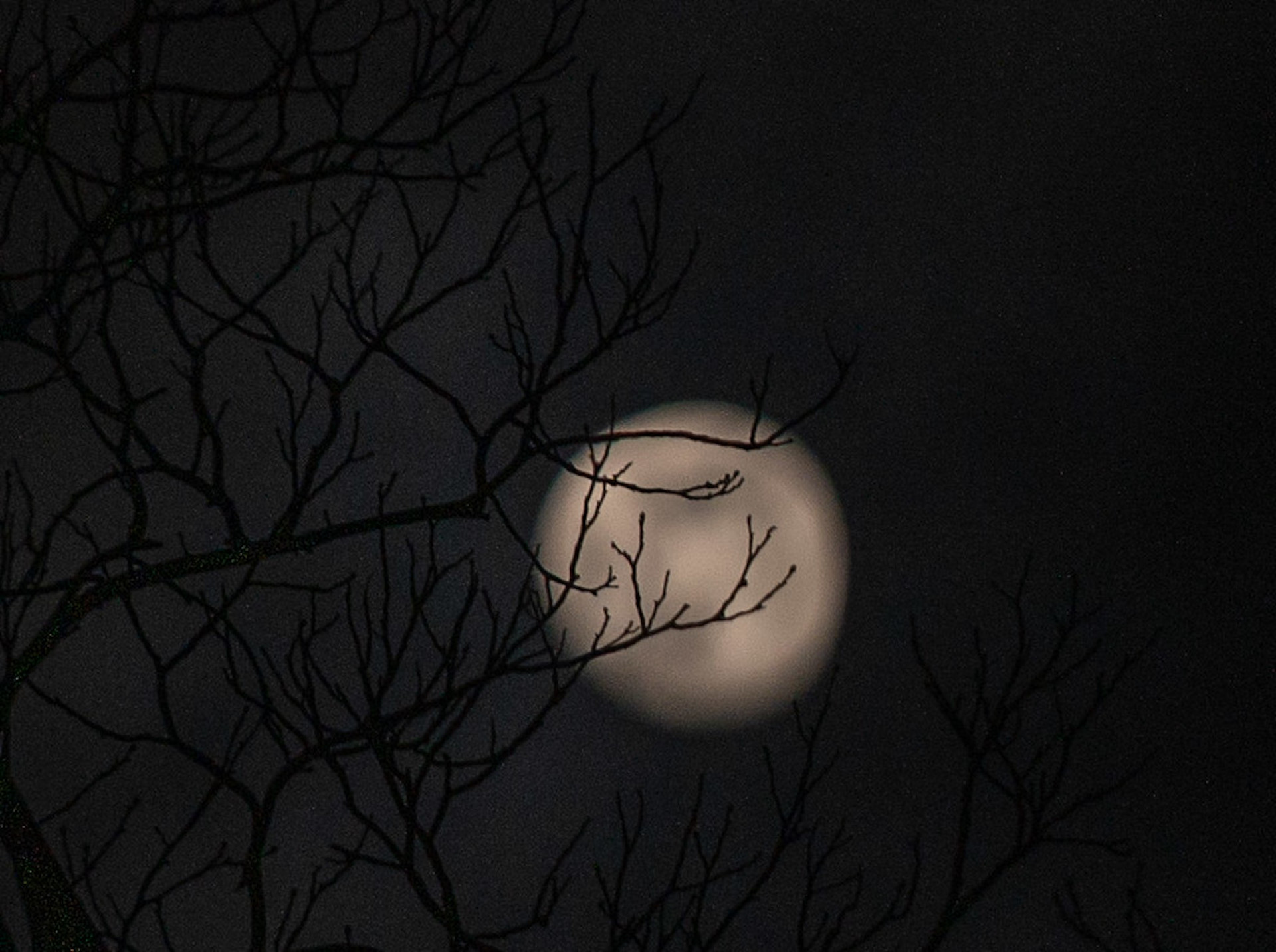

We study the self and try to grasp realization. We experience riding in a boat and have the misconception of the shore moving when it is the boat that moves. We watch the shore, the water, and the self. We turn the dharma wheel; we perceive the seasons and discern their qualities. We see the moon, feel dew, and gaze at the sky. We know depth and breadth, and we experience the dharma filling our body and mind. We see land and feel the undulation of ocean waves and smell the salt water; our eyes scan the horizon. Fish swim, birds fly, and the world is dusty. We listen to our environment and we know. We walk the path of the dharma and we realize that this is the place: solid and alive beneath our feet. We experience the intimacy of practice-realization, verifying the Buddha Dharma in this body and with this mind.

Yet, we have doubts about whether this very body and mind is buddha even as Dogen writes in Shobogenzo “Hotsu Bodai Shin” (Bringing Forth the Mind of Bodhi), “The real marks are the real marks of suchness; suchness is the present body and mind. We should bring forth the [buddha] mind with this body and mind.” These doubts arise because of the limitations of our ability to perceive reality’s presencing as codependent and cooperative function, yet salvation can only be achieved through our senses, not despite them. This is “bring[ing] forth the [buddha] mind with this body and mind,” and this too is part of Dogen’s message in “Genjokoan.”

Because it is this body and this mind, we can study and see reality’s functioning in our own life through examining both our delusions and realizations. We may struggle with the impermanence of flowers and the pervasive nature of weeds, yet we can, through our intimate “seeing” and “hearing,” be liberated from our selfishness and suffering. How else can you be enlightened by this world except by living your particular life as a human discovering harmony with self, other, and all being(s)?

How else can you be enlightened by this world except by living your particular life as a human discovering harmony with self, other, and all being(s)?

This self (with all of its difficulties) is, for each of us, the fulcrum point of awakening. This waking up is opening to all of our experience (both delusion and realization) and using this body and mind to express an enlightened response. We cannot jettison one to attain the other.

Dogen’s writing is about how this body and mind perceive and thereby awaken with the samsaric world, which is both delusional and amazingly vibrant and beautiful as bodhi mind. We walk with blue mountains, and we and our teachers are like twining vines supporting each other and learning together. We are bodhisattvas sitting in the fire of the blue lotus. Samsara becomes a crucible for awakened response. All this is sensual and intimate. It is the how and the is-ness of our senses. Our perceptions are dharma gates to realization. They are the place and the way unfolding as genjokoan.

♦

From Meeting the Myriad Things © 2025 by Shinshu Roberts with contributions by Shohaku Okumura and Zuiko Redding. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

Astrong

Astrong