Moral Philosophy and Zen

An Australian Zen Buddhist teacher on the distinction between virtue ethics and utilitarianism in developing values The post Moral Philosophy and Zen appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

An Australian Zen Buddhist teacher on the distinction between virtue ethics and utilitarianism in developing values

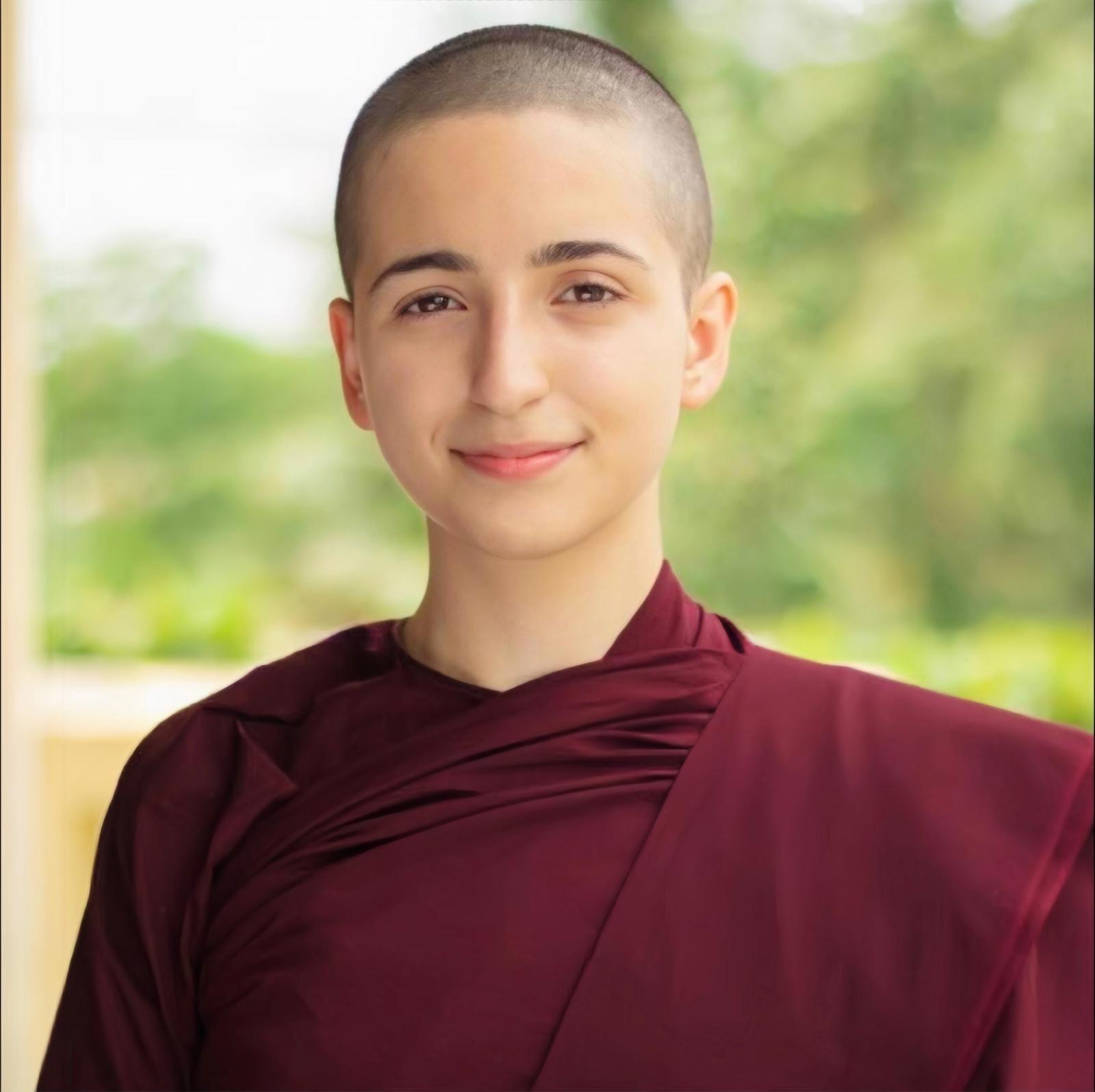

By Geoff Dawson Mar 09, 2025 Image via Ordinary Mind Zen School Sydney

Image via Ordinary Mind Zen School SydneyRenounce all evil

Practice all good

Save the many beings

—Prelude to the Ten Grave Precepts

What underlies all moral philosophy is whether life in all its many forms has value or not. If there is no value in anything, then what is the point in living a moral life? We could just live in a self-centered way to maximize pleasure and to promote the survival of the fittest. Further, is value, like meaning, just something human beings project onto life, or is there intrinsic value and sacredness in all forms of life?

In one of our Zen sutras, Torei Zenji’s “Bodhisattva’s Vow”, we recite:

When I regard the true nature of all things and all living creatures,

I find them to be the sacred forms of the Tathagata’s never-failing essence.

Each particle of matter, each moment, is no other than the Tathagatha’s inexpressible radiance.

These statements imply that a value runs through all things and all living creatures, and it follows that the value of all things and all forms of life is something that is discovered through spiritual insight, not something that we progressively learn or something we project onto life.

These statements are at the very core of understanding Zen practice and have enormous relevance for how we approach the precepts. We don’t renounce evil and practice the precepts to become good but rather to discover the inherent goodness that has always existed within us. It can be likened to cultivating a garden, the seeds of goodness are already in our unconscious just as the seeds of flowers already exist in the earth. But they need the sunshine of mindfulness and the water of compassion to help them grow.

This is true for the developing child, who needs the love and mindfulness of parents to bring their goodness to fruition, and it is also true for an adult Zen practitioner, who needs to eventually learn how to bring mindfulness and compassion to their own inner life. Practicing in the company of a spiritual community with friends of likeminded values makes a great difference in supporting this ongoing spiritual, emotional, and moral growth. It is far more difficult to do it on your own.

This understanding of the intrinsic value of goodness is in contrast with the most dominant paradigm in contemporary science and academic philosophy, which in turn broadly influences public opinion—the reductionistic and deterministic idea that human beings are just machines, a bundle of causes and effects that have no free will and no inherent values. This reductionistic view even tries to explain consciousness away as simply a biological process in the brain. In the mechanistic reductionist model, there is no space for values because science is supposed to be value-free in order to be objective. Yet it is blind to its own paradox. To paraphrase Iain McGilchrist, if science is about the uncompromising pursuit of truth, one assumes that truth must be something that is valued!

Zen’s aspiration is experiential, not academic. You don’t have to prove the existence of a god before you commit yourself to living a good life. Otherwise, you may never get started.

The flaw in this prevailing view is that it is assumed that because it is scientific it must be right, but among the elite scientists and philosophers in the world today, and particularly those who understand quantum physics and quantum biology, there is no rock-solid basis for this reductionistic and deterministic view at all. It is a chimera. It is known as scientific dogmatism and its adherents can hold their views as rigidly as any fundamentalist religious cult.

The alternative spiritual or religious view is that consciousness, free will, creativity, value, beauty, goodness, sacredness are ontological primitives. In other words, they have always existed and, like time and space, are the fundamental basis of the universe, not add-ons that are projected onto the world. In Zen we call it buddhanature.

This does not imply that a god made the universe—at least from a Buddhist perspective. But Buddhism is not necessarily atheistic either, as some people believe. It is just that practicing Buddhists aren’t interested in proving or disproving the existence of a god through logical discourse, because it just seems like an endless waste of time that could be better used in doing something good. Zen’s aspiration is experiential, not academic. You don’t have to prove the existence of a god before you commit yourself to living a good life. Otherwise, you may never get started.

The scientific reductionist paradigm is not necessarily amoral but often goes together with a form of moral philosophy called “utilitarianism.” As McGilchrist states:

The dominant approach to ethics in our culture is utilitarianism, the belief that what is good is so because it issues in utility. Given that the governing value of the left hemisphere is to aid manipulation of a creature’s environment, this is exactly what we would expect … if the left hemisphere were trying to give an account of what goodness might be … it substitutes for the complexity of reality a series of cause and effect mechanisms, with the ultimate focus on outcomes; it suggests such outcomes can be assessed by calculation (the greatest happiness of the greatest number) and in keeping with its lesser emotional and social intelligence, removes the central interiority of morality and replaces it with the externalities of the kind it prefers. It then calls itself objective, thereby implicitly trumping all competitor theories, and installs itself in university departments across the world.

The alternative to utilitarianism is virtue ethics, a right-hemisphere-oriented approach to morality that focuses on the inner attitudes and intentions of the person, and which embraces humility and compassion rather than calculated outcomes. The practice of the Zen precepts is aligned with virtue ethics, not utilitarianism. As David Misselbrook puts it: “Virtue ethics is ethics for grown-ups living in a complex world, with far more than fifty shades of grey.”

In considering whether to take up the precepts or not, it may be useful to:

Reflect on what family and cultural norms have shaped our understanding of morality Reflect on whether we hold the cynical view that it is only self-interest that drives human behavior Reflect on whether we consider ourselves responsible for our speech and actions in the world, or whether we quite literally hold the view, “my brain made me do it; or my dysfunctional family background is responsible; or the oppressors of my class, race, or gender identity are responsible.”Just like an alcoholic attending a twelve-step program to give up drinking, it is inherent in taking up the precepts that we fully embrace a sense of personal responsibility. For someone entering a twelve-step program the message is: “No one is responsible for your drinking except yourself.” When you take up the Zen precepts: “No one is responsible for the harm and suffering you create in the world except yourself.”

♦

Excerpted from The Ten Zen Precepts: Guidelines for Cultivating Moral Intelligence by Geoff Dawson. © Geoff Dawson, November 12, 2024,

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes