Nothing to Be Gained

The late Antaiji abbot Kosho Uchiyama Roshi on practicing without expectation. The post Nothing to Be Gained appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

The late Antaiji abbot Kosho Uchiyama Roshi on practicing without expectation.

By Kosho Uchiyama Roshi Mar 25, 2025 Monks during zazen meditation in the Zazen Hall, Elheiji Zen Monastery, Japan. Photo by Ursula Gahwiler / Alamy Stock Photo

Monks during zazen meditation in the Zazen Hall, Elheiji Zen Monastery, Japan. Photo by Ursula Gahwiler / Alamy Stock PhotoAny discussion of buddhadharma will be one of mushotoku 無所得—that is, nothing to be gained. The meaning of shōjin is not just an unceasing diligence through which we’ll benefit in one way or another. It must be a shōjin or unceasing diligence with nothing to be gained.

Sawaki Roshi often said, “No matter how long you sit zazen, it won’t come to anything. And if you don’t understand that, then zazen will really be good for nothing.” When I recall Roshi’s words, I can’t help remembering an incident concerning a certain elderly woman. Obviously, the woman wasn’t always elderly. When I first became a monk, I think she must have been around fifty years old. Anyway, even at that time, she had already regularly attended several sesshins with Sawaki Roshi. Until Roshi grew ill and could no longer sit sesshin, this woman sat with him. I suppose you could say she was practicing in the shōjin style.

Now, it was during the period when Roshi’s legs could no longer support him and he was settling into his final years at Antaiji that, one day, a letter came from the son of this now elderly woman. In the letter, he wrote, “My mother is now currently ill with stomach cancer and greatly suffering. What I can’t understand is why she, despite having sat zazen for many, many years with you, must suffer in such a way? She’s suffering so terribly. Can’t you do something for her?” The woman must surely have heard Sawaki Roshi’s words so often that she would have had calluses on her ears: “No matter how long you sit zazen, it won’t come to anything. And if you don’t understand that, then zazen will really be good for nothing.” Still, somewhere inside her, this woman must have continued to think, “Well, even though Roshi says that kind of thing,

actually, a little something must happen.” I’m sure that those thoughts would have only added more to her suffering from cancer. Around that time, as I mentioned, there was no way I could simply say to Roshi, who was already elderly and not well himself, that so- and- so is suffering from cancer and I must leave you for a while and go up to Tokyo to talk with her.

I think this sort of thing happens all the time. As long as you’re thinking that if you sit zazen for a while your situation will change for the better or that you’ll have more willpower— that’s all a kind of bait. It’s not sitting without any expectation of gain—mushotoku. It’s not sitting emptiness—kū 空. And because of that, we’re no longer talking about buddhadharma. Saying that everything is empty, or that all things are without self, or that nothing is to be gained no matter how long you sit zazen or practice Buddhism or diligently apply yourself to all your actions, it all must be based on what Sawaki Roshi said: it won’t amount to anything.

No matter if we have practiced for many years or have been diligent, clinging to the idea of getting some favorable condition because of our practice or diligence is not following buddhadharma.

In Pure Land Buddhism there is this story. A man who had recited the nenbutsu his whole life passed away. As the old man trudged along and crossed to the other side of the Sanzu River, he looked up and saw a gate in the distance. Delighted with himself, the old man was thinking, I guess there was some value in reciting the nenbutsu all these years. I’m on my way to paradise. As he approached the entrance gate, he saw a fierce demon standing there and was surprised. When the man asked the demon about it, the demon growled, “Don’t be a fool. This is the gate to hell.”

Of course, this is just a story, but in fact I rather think that mistakes like this occur quite frequently. Why wouldn’t anyone expect dying to be painful? That you’ve chanted the nenbutsu all your life or sat zazen for many years, so therefore, death should be painless—who would believe such nonsense?

We all must become more aware of this and acknowledge it. I think there are too many people these days who have never seen anyone die. Whether someone becomes ill or gets injured in an accident, right away, someone calls an ambulance, and everything is left to the doctor in the emergency room of the hospital.

Speaking of someone dying, I think far too many people just see some actor on television who looks to be in severe pain, says a few last words, and bows his head. “Oh, he’s gone!” They assume that’s what death and dying are like. Dying, however, is nothing like such foolishness.

It appears recently that any number of people have been thinking that they want to die peacefully. So suddenly lots of them have been paying their respects to the local temple. Just the fact that so many people show up at the temples only goes to prove that one doesn’t die so easily.

Being on the verge of death does not just mean that time when we physically stop breathing. As human beings, once we’re put into that category of “elderly” or “senior citizen,” we need to acknowledge the fact that we are in the process of dying. Once we get past sixty-five, we ought to recognize that we are in old age. I feel that we should not expect to recover from a serious illness and recognize that sooner or later such an illness will be closely connected to our death. That we may recover from an illness when we are young but not when we get old is just a matter of common sense. Our blood pressure is through the roof or we have hardening of the arteries and there’s little chance of recovery, yet we still cling to the idea that something about it is wrong—that is just frantically struggling in desperation. I hope that when we reach sixty- five, we can give up struggling. That’s called ōjōgiwa ga yoi 往生際が 良い—knowing when to give up.

Despite having become old, there are people who pretend to be strong and go around complaining about the thinking of young people today or who boast that they will beat death. I just think that’s going too far. What is most critical in Buddhism is an attitude of mushotoku or nothing to be gained. No matter if we have practiced for many years or have been diligent, clinging to the idea of getting some favorable condition because of our practice or diligence is not following buddhadharma.

⬥

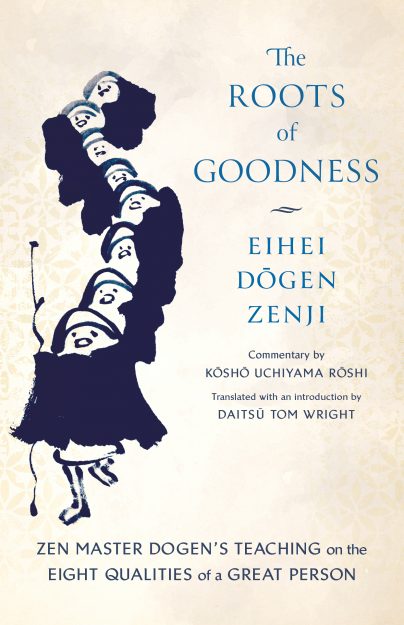

From The Roots of Goodness: Zen Master Dogen’s Teaching on the Eight Qualities of a Great Person by Eihei Dogen Zenji, commentary by Kosho Uchiyama Roshi, translated with an introduction by Daitsu Tom Wright. Translation © 2025 by Daitsu Tom Wright. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

Konoly

Konoly