OECD slashes global growth prediction on Ukraine war and China's zero-Covid policy

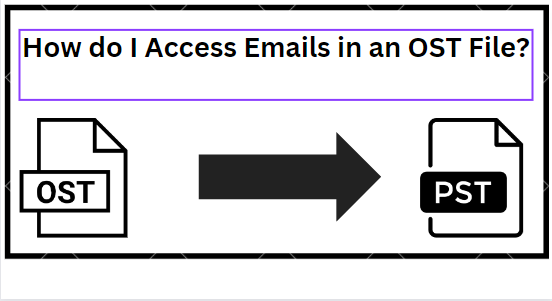

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has become the latest international institution to cut its predictions for global growth this year.

The OECD estimates that global gross domestic product [or GDP] will reach 3% in 2022 — a 1.5 percentage point downgrade from a projection done in December.

Nurphoto | Nurphoto | Getty Images

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has become the latest international institution to cut its predictions for global growth this year, but has downplayed the possibility of a prolonged period of so-called "stagflation."

The OECD estimates that global GDP will hit 3% in 2022 — a 1.5 percentage point downgrade from a projection done in December.

"The invasion of Ukraine, along with shutdowns in major cities and ports in China due to the zero-COVID policy, has generated a new set of adverse shocks," the Paris-based organization said in its latest economic outlook Wednesday.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine is having massive ramifications on the global economy, but China's zero-Covid policy — a strategy Beijing uses to control the virus with strict lockdowns — is also a drag on global growth given the importance of the country in international supply chains and overall consumption.

The World Bank said Tuesday that it had also turned more negative on global growth prospects. The institution said global GDP would reach 2.9% this year — an estimate lower from its 4.1% forecast in January.

The OECD said in its report Wednesday that the downgrade, in part, "reflects deep downturns in Russia and Ukraine."

"But growth is set to be considerably weaker than expected in most economies, especially in Europe, where an embargo on oil and coal imports from Russia is incorporated in the projections for 2023," it said.

The European Union in late May moved to impose an oil embargo on Russia, after agreeing the previous month to also stop coal purchases from the country. The bloc has been heavily dependent on Russian fossil fuels and cutting some of these supplies overnight will have a significant economic impact.

Nonetheless, the euro zone, the 19-nation region that shares the euro, and the United States do not differ much in terms of their economic outlook. The OECD said the former will grow 2.6% this year and the U.S. will expand by 2.5%.

For the United Kingdom, where the cost of living crisis is also an economic issue, GDP is seen at 3.6% this year before slumping to zero next year.

"Inflation [in the U.K.] will keep rising and peak at over 10% at the end of 2022 due to continuing labour and supply shortages and high energy prices, before gradually declining to 4.7% by the end of 2023," the OECD said.

The global macro picture has darkened for emerging economies, notably because they are expected to be hurt the most from food supply shortages.

"In many emerging-market economies the risks of food shortages are high given the reliance on agricultural exports from Russia and Ukraine," the OECD said. China is seen growing by 4.4% this year, India by 6.9% and Brazil by a marginal 0.6%.

No stagflation?

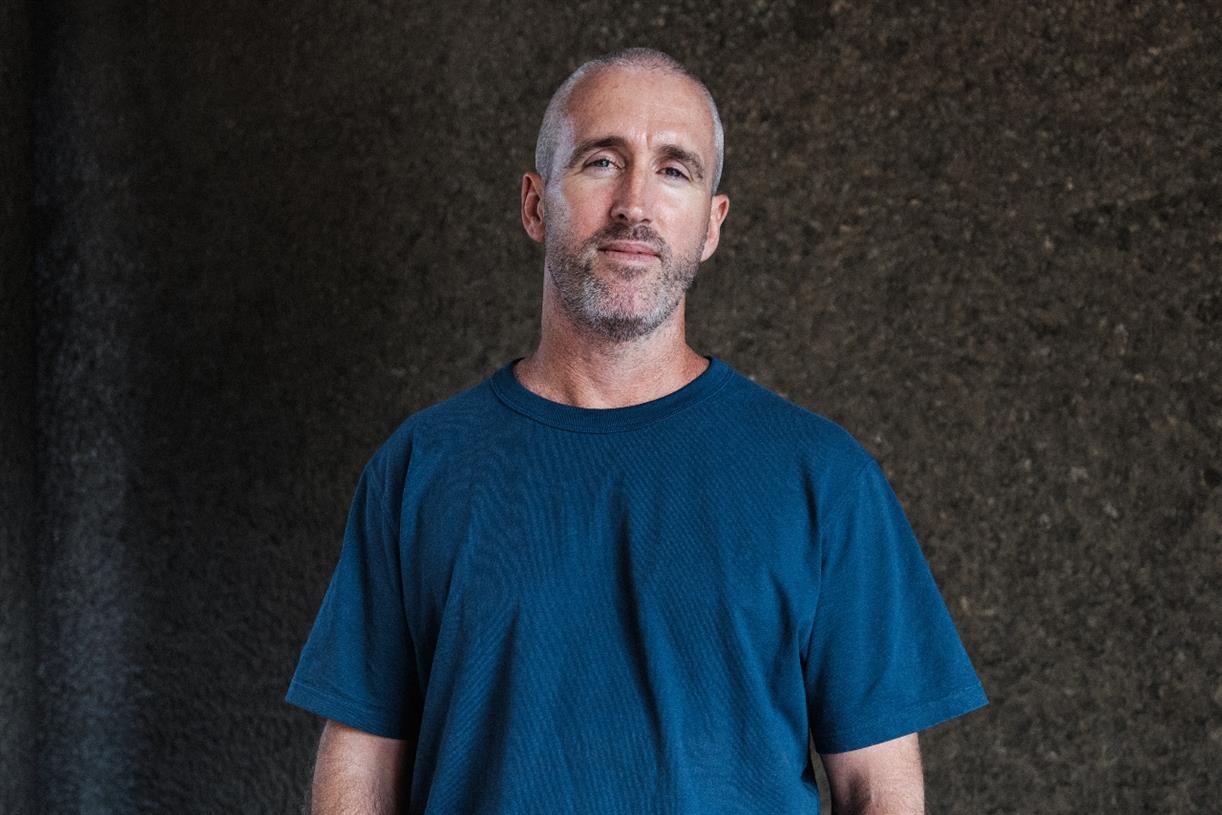

Mathias Cormann, secretary general of the OECD, said that despite the difficult economic environment, it's unlikely that the global economy is heading into a period of stagflation — where an economy sees high inflation and high unemployment alongside stagnant demand as experienced in the 1970s.

"We do see some parallels with the experience in the 1970s but we do not use the term stagflation, we do not believe it is the right term to describe what we are observing in the global economy now," he told CNBC's Charlotte Reed.

"Essentially most countries have gone through four quarters of very strong growth and yes we have inflation, we expect elevated inflation to last for longer, but we do expect it to subside throughout the second half of 2022 to the end of 2023," Cormann added.

The World Bank had said Tuesday that risks were growing on potential stagflation and warned that this would make the lives of those in middle and low-income economies even harder.

BigThink

BigThink