Op-ed: The EU’s rewiring due to the war in Ukraine is game-changing, if it doesn’t short-circuit before the job is done

European leaders and citizens must understand what they are doing isn't just for Ukraine but even more for themselves.

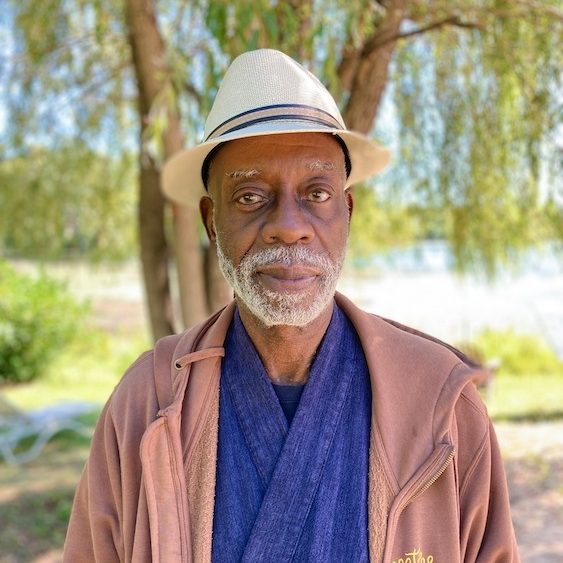

U.S. President Joe Biden, center, attends a working lunch with other G7 leaders to discuss shaping the global economy. The Group of Seven leading economic powers are meeting in Germany for their three-day annual gathering.

Kenny Holston | The New York Times via AP, Pool

Europe has been rewiring itself in impressive ways in the five months since Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine.

The coming weeks will show whether that work of building a more resolute European Union for a future of new security challenges will continue. Or, instead, will the rewiring short-circuit before the job is done in the face of rising economic headwinds and Putin's grinding war of attrition.

Thus far, the EU has remained unified with the United States and others behind an unprecedented set of sanctions on Russia. Further, it has begun to strengthen its hard power through increased defense spending, and it has moved swiftly to reduce its shameful energy dependence on Moscow. Most recently the Group of Seven nations appears poised to announce an import ban on Russian gold.

In ways Putin never envisioned when he hatched his war, the EU has committed itself to Ukraine as a democratic, independent, and European country through billions of euros of economic support, unprecedented arms deliveries, and now an offer of membership candidacy to Ukraine and Moldova.

Yet as impressive as the EU rewiring project has been thus far, it's likely to short-circuit in the months ahead unless the political conviction grows even stronger around this historic moment. That will demand faster implementation of new defense and energy policies — and greater support for Ukraine.

As Putin gains ground in Ukraine, with new strikes on Kyiv today almost certainly timed to coincide with the G-7 meeting in Germany, it will take all the political will European leaders can muster. They will face greater public pressures to end the war with benchmark gas prices climbing an additional 15% in the last week amidst the double shocks of Russian cuts and a fire at Freeport LNG in Texas, with inflation reaching 8.1 % in the euro area in May, and with economic recession dangers rising rapidly, given the threat of Russian gas cutoffs this winter.

On another front, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde summoned her colleagues to an emergency session last week in Frankfurt that was designed to generate solidarity around steps to pre-empt any danger of a new euro zone debt crisis reaching Italy from the dual shocks of rising inflation and slowing growth.

Putin is counting on the usual fatigue and political divisions that set in among Western democracies when they must weigh growing domestic concerns against international dangers. He's seen enough to encourage him, including newly re-elected Emmanuel Macron's failure to win a majority in the National Assembly, the first time in 30 years that's been denied the French president.

And for all the impressive arms shipments and economic support the Biden administration has delivered Ukraine, the weaponry firing range of some 50 miles remains insufficient to stop the Russian carpet-bombing, for fear of expanding the war.

Beyond that, Putin knows U.S. mid-term elections are likely to weaken Biden further amid domestic disputes over the Supreme Court's overturning of the Roe v. Wade abortion protections and gun law disputes. Even as Putin's war grows uglier, Americans are seeing less of it on their TV screens.

Meanwhile, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is also looking weaker than in his first days in office, as he this weekend hosted the G-7 leaders in the Bavarian Alps.

Scholz faced such a storm of criticism that he's been dragging his feet on heavy weapons deliveries to Ukraine that his Defense Ministry was compelled to publish a full list of completed and planned deliveries, including seven self-propelled Panzerhaubitze 2000 howitzers that at long last have arrived in Ukraine.

It's worth remembering that Europe's greatest moments of forward progress typically come at times of crisis, as has been the case again following Putin's war in Ukraine. It's at such times that member states better manage their divisions and work more effectively around the EU's mind-bending bureaucracy.

The problem is that the current European divide that looks hardest to fix is a fundamental disagreement over how important a Ukrainian victory is and what it would take to bring it about.

The closer you live to Russia as a European Union citizen, the more you argue, as I did in this space on June 5, that Putin doesn't need the diplomatic off-ramp that Macron is offering but rather the dead-end that can only be brought by tougher sanctions and a more effective Ukrainian counter-offensive backed by longer-range weapons.

Russia's closest neighbors know that a bad peace where Ukraine gives up new territory can only provide a respite before Putin resumes his imperial efforts to take all of Ukraine and ultimately other former Soviet areas.

In Western Europe, the desire is greater for a peace that would end the war now, even if the outcome leaves Putin in power and, as Macron has said, avoids humiliating him.

"Despite the celebratory rhetoric in Brussels about the European Union's surprisingly robust response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine," writes Eoin Drea this week in Foreign Policy, "the war has not united the bloc in any unprecedented or transformative way. In fact, it's having exactly the opposite effect. Beneath the soaring vista of Ukraine as a catalyst for a more muscular and geopolitically effective EU lie deep divisions, shifting allegiances, and a much more complex reality."

Counterbalancing that gloom, France's Macron, Germany's Scholz, Italian President Mario Draghi, and Romanian President Klaus Iohannis visited Kyiv on June 16. Shortly after they returned, the European Parliament voted with 529 votes to 45 against and 14 abstentions to adopt a resolution calling on the Heads of State or Government to grant EU candidate status to Ukraine the Republic of Moldova, which they have now done.

That symbolism must now be complemented by even greater substance. The rewiring of the EU has only just begun to strengthen its defenses, diversify its energy sources, tighten its transatlantic links and ensure Ukraine's survival as a sovereign, free European state.

To stay the course, European leaders and citizens must understand what they are doing isn't just for Ukraine but even more for themselves. The lessons from two devastating World Wars and a Cold War are that staying unified is a pre-requisite for victory and that appeasing despots is always self-defeating.

— Frederick Kempe is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Atlantic Council.

MikeTyes

MikeTyes