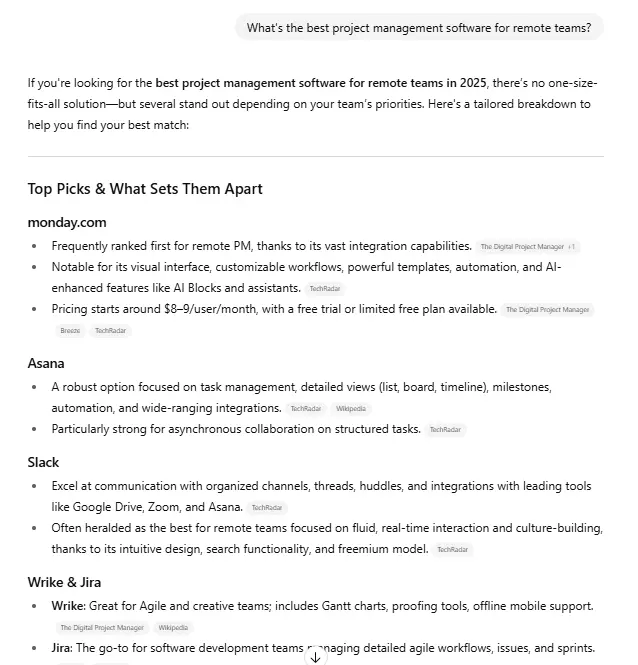

Remembering as an Act of Cultivating Clear Awareness

As a part of the May We Gather series, Chan teacher Rebecca Li reflects on the role of memory in healing and growing in wisdom and compassion. The post Remembering as an Act of Cultivating Clear Awareness appeared first...

The following dharma talk was given in conjunction with May We Gather, a collaborative project of commemoration and healing, by and for Asian American Buddhists and their spiritual friends. The project marks the three-year anniversary of the 2021 Atlanta spa and massage parlor shootings with a series of online talks and a pilgrimage in Antioch, California, this Saturday, March 16, 2024. For more information or to register, visit their website.

Thank you for joining me.

My name is Rebecca Li, and I’m a practitioner and teacher of Chan in the lineage of Chan Master Sheng Yen.

If you have not heard of Chan, it is the Mandarin Chinese pronunciation of the same character that’s pronounced as Zen in Japanese. I’m delighted to be here to share my thoughts on remembrance, repentance, and healing with you today. It’s been quite a journey. I’m grateful for the opportunity to reflect on this topic as a Chan practitioner, and I hope you’ll find something useful for your reflection and practice.

To help you understand where I’m coming from in discussing remembrance and repentance as a Chan practitioner, it may be helpful to talk a little bit about what I mean by Chan practice. By Chan practice, I’m referring to the practice of silent illumination. It is a practice where we relax into each emerging present moment as it is, maintaining total clear awareness of this body-mind in this space, moment after moment. The practice of silent illumination is to be fully here, as Chuang-Tzu, who articulated the practice of silent illumination, wrote: “Stay with that, just at that. Stay with this, just at this.” This clarity allows us to respond to what is going on skillfully, do what needs to be done, to reduce harm, and bring benefits made possible by causes and conditions.

But we find it quite difficult to be with the present moment as it is. We notice all these habitual tendencies to want to block out certain aspects of the present moment we don’t like, or make some part of it other than what it is. These are the habits of craving and aversion the Buddha was talking about that create suffering. Do you recognize some of these habits? Now, when we stop reacting to the present moment with these fixations, it is just the present moment as it is: there is no suffering. The teaching is quite straightforward, but [having a] conceptual understanding is not enough. We may know that giving rise to vexation creates suffering, and that we should stop doing so. Yet these habitual reactivities are quite entrenched. They sneak up on us and take over when we are not paying attention. That’s why we need to engage in [a] meditative practice, to train the mind to cultivate moment-to-moment clear awareness to help us recognize ways in which we generate suffering.

When we suffer less, we are less prone to cause harm to others. We are less consumed by our suffering. When we are not as consumed by suffering, we can connect with our natural capacity for empathy, and compassion.

Oftentimes, we may be doing something with good intentions, without clear awareness of our compulsive thought-habits. They can be quite subtle, however. We may inadvertently be perpetuating habits that cause suffering to ourselves and bring harm to others even though that’s not what we intended. As we maintain clear awareness of how these unhelpful habits are triggered, and how they unfold moment to moment, we can stop perpetuating them by not believing in them and not acting on them. This is how we can unlearn these habits as we gradually stop identifying with them. When we suffer less, we are less prone to cause harm to others. We are less consumed by our suffering. When we are not as consumed by suffering, we can connect with our natural capacity for empathy, and compassion. This compassion is founded on clarity and realization of our interconnectedness.

Practicing this way will help us fulfill the potential of remembrance and repentance as a way toward healing. The act of healing [while] remembering a past event creates a space to honor the experience of everyone whose life was touched by an event. We cannot change the past or undo what happened, however much we wish we could. When harm [is] done, its effect reverberates because we are interconnected. Remembrance gives us an opportunity to reflect on and connect with the event, how the event affected us, so that we do not inadvertently generate more suffering.

The opportunity to reflect gives us permission to fully experience the thoughts and feelings triggered by the events. They may include fear, grief, anger, anxiety, sadness, or feelings we can’t quite articulate. Instead of repressing them, we can reconnect with our humanity by allowing these feelings into awareness as they are and see for ourselves that they are not fixed entities. We do not need to let these thoughts and feelings define us. When [the] opportunity presents itself, we can hold space for others to share and reflect on how the event affected them. Our full presence, with an open heart, supports their journey of healing. When they feel fully heard and seen, the wall they have put up between themselves and others melts away. They open their hearts to the lovingkindness already around them, and allow themselves to be supported by others. This also allows them to reconnect with themselves fully, [and to] recognize their shared humanity. In this way, we support each other in our collective healing through remembrance.

We may know what we are supposed to do as we engage in remembrance, but do we know what we are actually doing? As we maintain moment-to-moment clear awareness, we are afforded an opportunity to notice ways in which we get in the way of reconnecting with ourselves, thus blocking the healing process. For instance, are we stuck with our existing narrative of what happened and resisting opening our heart to reflect on our experience and that of others? Oftentimes, when an event happens, we interpret the information we [are] exposed to and create our idea of what happened.

For example, we may determine that [certain] people are the victims, [and other] people are the evil perpetrators. The evil people did this terrible thing to the poor victims. Sometimes, we may even elevate the “victims” into saint-like beings in our mind, or exaggerate the evilness of the “perpetrators” to strengthen our narrative. Does any of this sound familiar?

We also tend to characterize our feelings about what happened in a particular way. For example, we may characterize a feeling as anger, as in “I’m outraged by the harm done by the evil perpetrators to the poor victims.” To stick to this narrative, only anger is allowed into our awareness when we reflect on our experience. Think about it. What happens when we then learn that the “evil perpetrator” actually felt great remorse over what they did? Not only that, because their loved ones were deeply distressed by the harm caused by their actions, the “evil perpetrators” [were also] worried about the distress experienced by their loved ones.

If we open our hearts, we can’t help but recognize the full humanity of these “evil perpetrators.” Yes, they have done something quite harmful here, but they have also shown love and care to their loved ones and remorse over their mistakes. These are all very human emotions. So it is natural for us to feel empathy, feeling sympathy for everyone’s pain, and empathy with the terrible situation they find themselves in. Yet our desire to hold on to our existing narrative may keep us from letting this empathy into awareness. To hold on to the narrative, we may refuse to recognize the full humanity of these “evil perpetrators,” refuse to allow the idea that they can feel remorse and show love and care to others into our awareness. Only the idea that they did something terrible is allowed.

Think about how much tension it generates in us to keep those thoughts of empathy out of our awareness. We do all this to hold on to the idea that “this is an inherently evil person” to sustain our existing narrative. Not only that, we block out the empathy that naturally arises in us, disconnecting us from our full humanity. Can we see that we are generating more suffering, instead of healing, by doing so?

The opportunity to reflect on our experience with an open heart in remembrance allows us to notice our resistance to doing so. Instead of opening our hearts, we only want to remember our particular version of what happened. Now, there is no need to be frustrated with ourselves when we notice this resistance. That means there is some clear awareness we are practicing. When we notice that these unhelpful habits are closing our hearts, we can cultivate moment-to-moment clear awareness of how it is triggered and unfolds. As we stop believing in and acting on it, we can unlearn it, and open our hearts to everyone’s full humanity. It does not mean that we agree with everyone, or do not hold them accountable for their harmful actions. But we do not fall into the habits of dehumanizing and demonizing them. When we dehumanize and demonize, we’re breathing poison in our heart.

We’ve been talking about the tendency to hold on to our existing narrative of what happened as a way to block us from opening our hearts in remembrance. Another way we resist opening our hearts is by being too eager to forget. As we talk about remembrance, some of you may be thinking, “Why remember? Wouldn’t that be dwelling in the past? Aren’t we supposed to be in the present? Why not just forget and move on?”

I’ve heard these questions and comments by practitioners, when they were resisting the instructions to allow memories—when they arise—into their awareness, as they are, as in the practice of silent illumination. When thoughts of the past arise, we are experiencing these thoughts in the present. The question is, are we fully here to experience each thought as it unfolds, or are we busy blocking them out, tensing and agitating the mind, creating suffering?

As we cultivate moment-to moment-clear awareness of our subtle thoughts and feelings, we may notice that as we insist on forgetting, we are secretly wishing that by forgetting what happened, we can erase it as if it never happened. And if the fact of what happened can also be erased—poof—all our problems are solved, or so we believe. When we notice ourselves thinking this way, we can ask, “Are we harboring this secret wish, because we don’t want to accept that harm was done in the past and that we don’t want to deal with its effects? Do we know this is how we are affected by the events?”

Of course, it is understandable that we want to wish things away when they are difficult to face. When we say it out loud, though, we can see that [this is] some kind of magical thinking. That’s why we often won’t even admit to ourselves that we have these ideas. Now, there is no need to get mad at ourselves for harboring these thoughts. It is important, however, to be aware of them, so that we can stop perpetuating them inadvertently. Blocking them out of our awareness does not stop them from operating— rather, they lurk around beneath the service, and compel us to react in ways that cause harm, even when that is the opposite of what we want. This is why cultivating moment-to-moment clear awareness of subtle thoughts and feelings is important. It allows us to see that wishing that the past and its effects can be erased is to deny the law of cause and effect. We are resisting reality rather than staying with this, just as it is. We are generating suffering for ourselves.

What happened, and has that emotion [had] the fruition of its effects? With events that took place way back in the past, decades ago, or [even] further back, the effects have rippled out and [been] passed down [onto future] generations, shaping everyone’s lives, through the way we perceive our world, other people, and ourselves. Our lives are touched by what happened in the past, one way or the other, based on our causes and conditions. Forgetting does not mean that our lives are no longer affected by what happened. Forgetting, however, makes it harder to cultivate clarity of how we have been affected by past events, and reacted in ways that cause us suffering.

I once encountered a practitioner in a retreat who was eager to forget. He worked really hard to resist the instruction to allow what happened in the past into his awareness. And it turned out that he [had] been blaming himself for a violent event that happened in his family when he was young, and he has been punishing himself by being quite harsh on himself and those around him. This caused a lot of pain for his loved ones and [created] conflict with his family, to the point that his marriage was on the verge of falling apart. Yet he was unaware that his situation had anything to do with what happened decades back. This insight allowed him to release the compulsion to be harsh, and [since then] he has allowed a lot more love and tenderness toward himself and his family members. As a result, the entire family was able to heal together. When we notice the eagerness to forget, check to see if we are harboring the belief that we can erase what happened and its effect by forgetting, perhaps because it’s too difficult to face it.

Even if you’re not ready to engage in remembrance now, at least you’re aware that the event has affected you. That way, you can pay attention to how it may trigger habitual reactivities in you that cause suffering to yourself and harm to others. Recognizing that will allow you to stop perpetuating these unhelpful habits and reduce suffering. As we engage in the remembrance of what happened, especially in the distant past, we may notice ourselves thinking, “I can’t believe they did that, they should have known better.” When we react this way, we may be falling into the habits of judging people’s actions in the past based on the standards and understanding we have now. While we are aware that we may be doing that, it is easy to fall into this habit, because we tend to take for granted what we know now.

While some actions are morally wrong and harmful [now], they were often socially acceptable in the past. For instance, we are aware that generating greenhouse gas damages our environment, and we now know we should do what we can to reduce our emissions. Nowadays, most of my students carry around some kind of thermos or reusable water bottle for their beverage. Not too long ago, it was not uncommon for students to carry around bottled water in disposable plastic bottles. When people were engaging in these harmful but socially acceptable actions, they were merely doing what was standard practice at that time. It is especially true for collective harm done in the distant past. In other words, they really did not know better.

Looking back, we may feel remorse, shame, or embarrassment about the harm done in the past. The feeling of remorse can be so unpleasant that we want to get rid of it by pretending that it did not happen, and thus, [embracing] the eagerness to forget. So if you find yourself being eager to forget something, [trying] to erase it, and the urge to judge and be hard on yourself thinking “we should have known better,” remember to be gentle and kind to yourself. That you recognize this urge means that you are practicing. This clear awareness allows you to choose not to perpetuate and act on [this urge] so that you can stay on the path [toward] healing.

Remembering allows us to gain some clarity on what happened, recognize where mistakes were made, and what was done right. This way, we can avoid repeating the same mistakes and learn from them and grow. It is important that we also recognize what was done right, so that we do not fall into the habit of mistakenly characterizing what happened as all bad or all good. It’s usually more nuanced and complicated than that because we’re all humans.

It is also important to remind ourselves that the standard we have now is the result of a long process of collective learning from the past. To believe that we are superior to those in the past is to forget that every moment is the coming together of causes and conditions. The attitude and action of people in the past were partly shaped by their social and cultural environment. We think the way we do [this] because we live in our time. Remembering the past allows us to recognize the changes in attitudes and beliefs in society and how we have benefited from lessons learned collectively by previous generations who brought about the gradual change in attitudes and beliefs.

When we are not consumed by suffering, we are less prone to causing harm to others and we are more available to bring joys and benefits.

When we practice this way, cultivating total clear awareness, we naturally give rise to gratitude to everyone who came before us. This includes those who acted in harmful ways and those who push for positive change. If we have more inclusive and tolerant attitudes nowadays, for instance, everyone who engaged in discrimination and those who fought against this are part of the causes and conditions that made our present worldview and attitude possible.

That’s why we make offerings to all sentient beings, not just those who [we] agree with or like. Everyone played a role in co-creating the causes and conditions that came together each moment. When we practice this way, as we remember the past, by ourselves or in community, we can release the habit of separate[ness].

Remembering is part of the path to healing, to growing in wisdom and compassion. When we are not consumed by suffering, we are less prone to causing harm to others and we are more available to bring joys and benefits.

***

As we open our hearts to the effects of past events on ourselves and others in remembrance, we are afforded the opportunity to practice repentance.

Repentance is about the willingness to own up to and accept our responsibility in the harms done with humility and committing to not repeating these mistakes. That is how healing is possible. The practice of repentance is integral to our spiritual path to free ourselves from the unhelpful habits of suffering. In our intensive Chan retreats with the Chan master Sheng Yen, he would talk about the practice of repentance, and have us engage in the embodied practice of repentance prostration during these retreats. It is a powerful way to undo our unhealthy relationship with the past, as we try to avoid facing what happened in the past and resist recognizing and accepting the role we played and that had caused harm. We find ourselves getting stuck in these knots in our hearts when we try to rewrite the past or wish for a better past.

The practice of repentance is not about telling ourselves that we are a terrible person, hopelessly flawed, or defective. To practice repentance, we start with acknowledging that harm has been done. Doing so will open our awareness to recognize the role we played, [the] mistakes we’ve made. When we see clearly how our actions caused harm, we take responsibility for the effects of our action and commit to not doing that again.

In recognizing that harm has been done, we no longer need to expend energy, to deny reality. We may have the experience where you have done something that was hurtful to others, which is easy to do when we are agitated or scattered. When we acknowledge that our action has caused harm, we can apologize and find out what we can do to make up for our mistakes, and just do it. Then it is resolved, and everyone is free to move on. That mistake we made does not need to be turned into suffering. However, instead of recognizing that harm has been done, we often create more suffering by denying other people’s experience, telling them it is in their head, or that they are imagining things, or by demonizing others to justify and defend our effort to deny reality, the reality of what happened and the fact that harm was done, and that we played a role in it directly or indirectly.

It is amazing how much energy we expend doing that, to wiggle our way out of taking some responsibility. We can ask ourselves, “Does doing so free us from suffering or create more suffering?” If we are creating more suffering, do we want to keep doing that? Taking a moment to reflect often helps us realize that denying that we have made a mistake and caused harm is one of the habitual ways we react, even if that is not what we intend to do. This awareness allows us to realize that it’s true, that we are causing more suffering to ourselves by denying what happened. It’s not just some abstract dharma teaching. We can really see it for ourselves from our direct experience.

To defend our effort to deny that harm has been done, we put up a barrier between ourselves and others and get in the way of our natural capacity for empathy from arising when we realize that someone has been hurt. That is suffering.

Sometimes, when we are consumed by suffering, we become so attached to and identify with our suffering, that we may tell ourselves, “It’s my suffering. So what if I suffer?” In these moments, we can practice remembering that denying that harm has been done causes additional harm. Think about it, it’s painful to be told that our pain is not worth recognizing and have our suffering dismissed. When we find ourselves on the receiving end of someone’s refusal to recognize our pain caused by harmful actions, it is important to maintain moment-to-moment clear awareness of thoughts and feelings as they unfold, allowing ourselves to be fully felt, and seen and heard, as in the practice of silent illumination. Practicing this way will allow us to recognize the ways we may have inadvertently internalized these habits of denial, telling ourselves that maybe they didn’t do that, maybe that didn’t really happen, maybe I was imagining it. Or we blame ourselves for our feelings, telling ourselves that people do what they do, but I should not feel hurt. But we did feel hurt when we were made to feel invisible, perhaps experienced in the form of shame, anger, fear, or other emotions. Yes, it is true that these emotions are not permanent. They arose and perished. But it does not mean that they did not happen and we did experience it.

By telling ourselves that we are not allowed to have these emotions, we are cutting off some part of ourselves and causing suffering to ourselves.

The practice here is not about getting upset or frustrated with ourselves that we are doing this. We cultivate clearer awareness of our habitual reactivities so that we can unlearn the unhelpful ways in which we inflict more harm on ourselves after being hurt by other people’s actions. We may not be able to control what other people do. We can reduce our suffering by not falling into the belief that we are not worthy of being seen and heard as we are. When we recognize that harm has been done and people were hurt by these actions, we free ourselves to reconnect with our shared humanity, allowing our natural capacity for empathy and compassion to be revealed.

Even if we are convinced that this is the way to go, we may still feel hesitation or worry about what will happen if we stop doing what we’re familiar with, denying what happened. [We] think, “What if my world collapses? Maybe it’ll be totally terrible, what if I become consumed and paralyzed by guilt and shame?” Now, it is natural to feel anxious and hesitant when we move away from our familiar way of being. Keeping this in mind will help us make the first step. When we practice relaxing into the present moment, we feel the tension generated from denying what happened melting away. As we relax into clarity, we feel more comfortable with allowing thoughts and feelings into awareness as they are instead of blocking them out. In clear awareness, we may notice perhaps some guilt or shame, but we can also feel empathy and love for others.

There may not be a word to capture how we are feeling, and it’s OK. These feelings can all be here.

We may notice that we feel bad about causing harm or embarrassed by our mistakes and mad at ourselves. As we allow these feelings to coexist, we reconnect with ourselves more fully as we are. We realize how we have caused ourselves so much suffering by refusing to recognize [the suffering of others]. When we remember that every moment is brand-new, we can admit to ourselves, “Well, now I can see the mistakes were made, and someone is feeling hurt as the result.” Instead of agitating our mind by denying it, the clarity allows us to see what can be done within reason to rectify the situation and just do it.

At times, a relationship may have been damaged, and we accept the consequences of our action and take responsibility for it. In some situations, an apology may be appropriate and help alleviate the suffering of the people who were harmed. In other situations, apologizing may not be possible or appropriate, and we have to accept that.

Repentance is not about dwelling in self-disparagement, saying that “I’m so terrible, it’s all my fault. I have destroyed everything, and it’s all hopeless.” Doing so does not help alleviate anyone’s suffering. In agitating the mind with self-disparagement, we block ourselves from seeing clearly the appropriate actions to rectify the situation and end up causing more harm sometimes. The practice of repentance is to recognize that harm has been done and give rise to humility, sincerely admitting that we have made mistakes and caused harm; [that] we are genuinely sorry for what happened and vow to not make the same mistake again. And we can also do what we can to rectify the situation.

We may forget sometimes and make similar mistakes again, but we vow to move in that direction. When we practice repentance [in] this way, we are less likely to cause more harm and suffering.

A couple of months ago, when I was visiting a Penguin Conservation Center in the South Island of New Zealand, the arborist on staff who was hired to reforest the area said something that really touched me and reminded me of the practice of repentance. He told us that this rare penguin species was experiencing a drastic population decline because of loss of habitats. These penguins nest in the forest, and the trees in the area had been cut down by farmers from Europe generations ago. And he admitted that his family of farmers were among those who cleared the forest and made a good living [doing so] and [that] he benefited [with] financial success. He pointed out that his ancestors did what they did given what they knew and [what they] did not know and brought about the effects of deforestation that caused harm to these penguins. When the effects of deforestation on penguin population decline was known, a farmer created a conservation center with his land, and this arborist, a descendant of farmers who destroyed the penguins’ habitat, [decided to plant] thousands of trees each year to reforest the area for the penguins.

Both what he said and how he said it touched me deeply. And that’s why I’m sharing the story here, to illustrate the practice of repentance. He stated plainly that the action of his ancestors caused harm to these penguins. There’s neither denying that harm was done nor is there self-disparagement. There is a clear recognition of the fact that mistakes were made due to past ignorance of the effects of the action and the desire to improve their fortune. Once they accepted responsibility for [the] harms done, it [was] clear what needed to be done to rectify the situation, and they are committing [their] resources and lives to it. Yet he did not talk about himself or the farmer who established the conservation center as heroes, saving the penguins from extinction. Rather, the actions are the natural response to the recognition of one’s role in past mistakes that caused harm. Yes, they were not the people who cut down the trees, but it was clear to them that they benefited from the wealth created and the desire of the ancestors to give [their] descendants prosperity motivated their action. So they are doing what their causes and conditions allowed them to do to contribute to the bettering of the situation. The farmer has land and he donated some, the arborist is using his expertise to work on reforestation, and it’s going to be a collective effort, everyone chipping in what they can.

We do not need to be heroes or superhuman to accept responsibility for past mistakes and do our part to rectify them. We just need to reconnect with our full humanity and recognize our interconnectedness with all beings. When we give rise to humility and are truly sorry for what happened, that’s also the beginning of the healing process for everyone. When we stop denying that harm was done, we reconnect with ourselves and others more fully. This allows us to forgive ourselves. We recognize our ignorance in the past that resulted in harm, and are grateful that we know better now and can stop perpetuating harm and do what we can to rectify the situation. When we cause less harm, there is more inner peace and there is less suffering, and we begin our healing from the disease of misbelieving that we are inherently independently existing beings, or separate from others. When we realize that we are truly interconnected, it is obvious that when others suffer less, we suffer less. Other beings’ joy touches everyone, eventually. Bringing benefits to others is no different from benefiting ourselves. Those who were harmed too can start their healing process. It is painful to be hurt by others’ actions. It is even more painful when others deny our suffering. When those who hurt us admit it, accept their responsibility, and are genuinely sorry for their actions, the painful feeling passes and we can move on.

Of course, healing takes time. Our trust may have been shaken, and it takes time to repair. Fear or anger or other feelings may be triggered in similar situations, and it takes time to unlearn these conditionings. We need to be gentle and patient with ourselves in this process, but the healing process is no longer blocked by doubting whether we deserve to be loved and seen and heard. When we allow ourselves to recognize the fact that someone has done something to hurt us, we can start the healing process. We see for ourselves how we may also have caused ourselves suffering, by denying what happened and doubting our self-worth. As we truly see ourselves as deserving of love and being fully seen, we’re beginning to fully see and love ourselves.

Now, we may fall into the habit of blaming or doubting ourselves from time to time, because the habit can be quite entrenched. When that happens, it’s not a problem. There’s no need to get frustrated. We can continue to treat ourselves with tenderness and lovingkindness and patience, regardless of what happens. In this way, slowly but surely, we are on the path of healing together.

Thank you.

Troov

Troov

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=6e07dc5773&c=1)