Sangha Across Time

Following in the footsteps of Michael Dillon The post Sangha Across Time appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

I am standing in a shady, mossy graveyard next to a gray stone Anglican church. The church is at the edge of a high bluff in the town of Folkestone, overlooking the English Channel. The sand below is almost pink. Empty wooden piers jut out into the water, which is surprisingly aquamarine blue. France is visible across the channel, as bright green hills through a hazy mist.

I came to this church, and this town, because of Michael Dillon, a man who was born in 1915, and who died thirty years before I was born. I first encountered Michael Dillon in a cursory Google search. I believe my search was something broad, like “the first transgender man” or “who was the first transgender man?” I was driven by a fairly common urge: to know what had existed before me.

Ten years later, I recognize some of the fallacies built into that cursory search. Firsts are often created in hindsight, through the reconstruction and reshaping of history. People labeled female at birth have always lived as or like men. Names for that fact vary, according to time, place, and culture. Even the premise of woman and man is uneven terrain, subject to vastly different interpretations.

In the bar of images across the top of the computer, I see a regal bearded man, holding a pipe between his lips and looking to the side. In another picture, he strides in front of an English courthouse, in a well-tailored three-piece suit, holding a stack of papers under his arm. He is handsome, broad-shouldered, and tall. He passes as a man, without question. I would have loved to look like him.

For the purposes of transgender history, one of Dillon’s endeavors stands out above the rest: He was the first transgender man to undergo a phalloplasty. Between 1946 and 1949, the plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies (who had developed his innovative procedures working on disfigured WWI soldiers) performed thirteen experimental surgeries on Dillon in a rural manor house hospital in Hampshire. Using skin flaps from Dillon’s abdomen, Gillies successfully constructed the penis that Dillon believed would complete his transition.

Dillon had been interested in theology since he was a child. While a student at Oxford he dreamed of being a deacon in the Church of England, but he was barred from this role because of his female sex. This exclusion ushered in an early suspicion of Christian doctrine and the Church’s hypocrisy (though he maintained an abiding love of Jesus, whose core teachings he came to believe were virtually indistinguishable from the Buddha’s). Perhaps prompted by curiosities stemming from his transition, in 1945, Dillon enrolled at Trinity College Dublin to study medicine. And it would be after his sex change, while working in the merchant navy as a ship’s doctor, that he discovered the teachings of the spiritual teacher George Gurdjieff and his most prominent student, P. D. Ouspensky. Their approach, called “The Fourth Way,” attempted to synthesize Eastern and Western mystical paths into an accessible program of self-inquiry. Dillon committed himself to “The Work,” attending groups and subjecting his personality to rigorous analysis.

It was during this period that Dillon discovered Buddhism, in The Third Eye: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Lama, a wildly popular 1956 memoir by Tuesday Lobsang Rampa, an alleged incarnate lama and the son of senior advisor to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. Fascinated by what he read, Dillon wrote to Rampa and went to visit him in Ireland. Rampa was, in fact, a British man named Cyril Henry Hoskin—the son of a plumber who had never been farther East than England. In 1958, a year after Hoskin’s identity was revealed in British newspapers, Michael Dillon’s history of sex change was outed by the press. Convinced he needed to go into hiding until the controversy blew over, Dillon fled to India. Hoskin encouraged him to go, believing Dillon needed spiritual guidance, and a spiritual home.

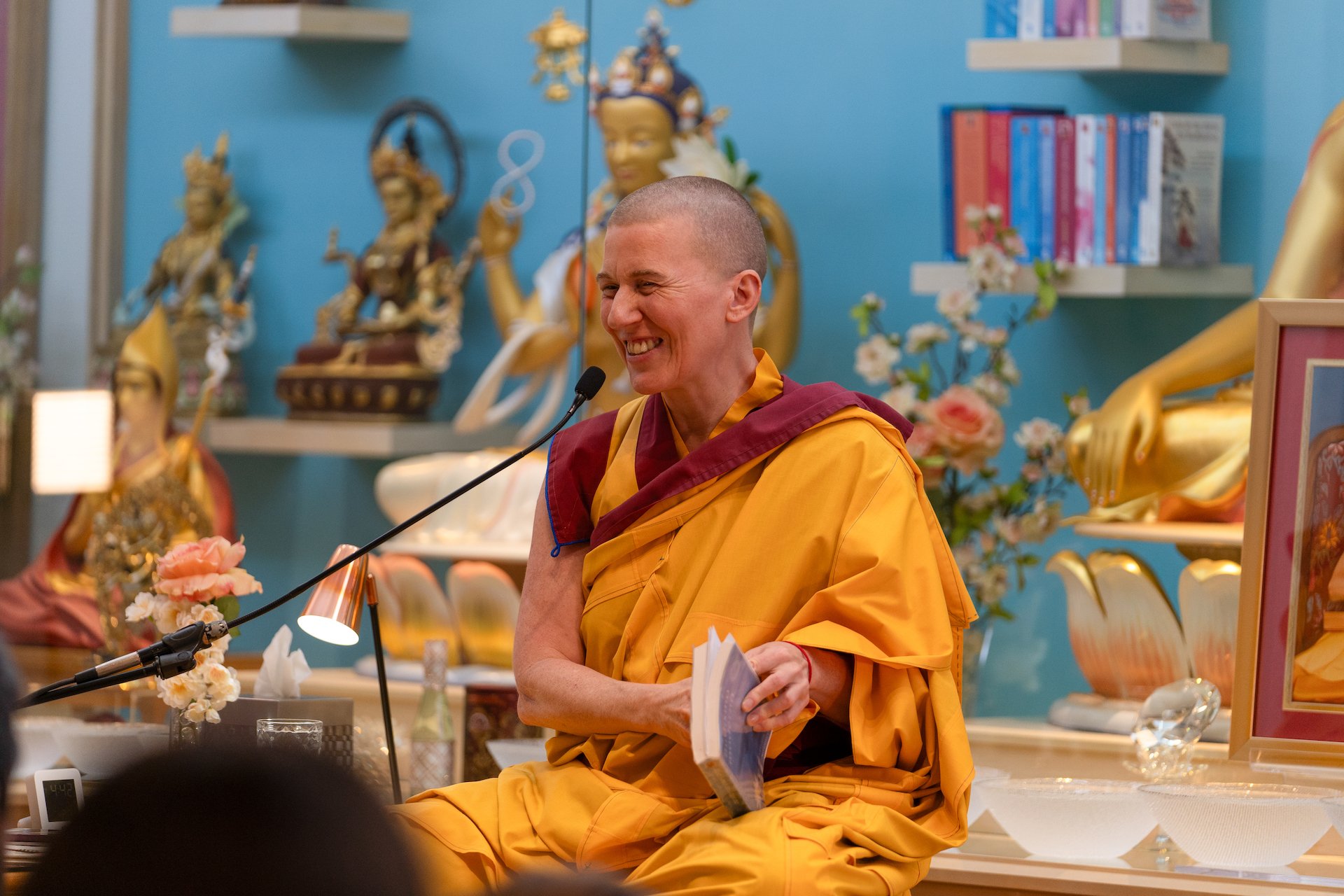

After some time traveling through India’s Buddhist heartland, Dillon connected with an English monk named Sangharakshita, ordained in the Theravada tradition. It was Sangharakshita who gave Dillon his new name, Jivaka, after the Buddha’s first physician. Dillon sought a teacher and a guru in Sangharakshita, but when Dillon pursued ordination as a monk in Sarnath’s Theravada monastery, Sangharakshita wrote a letter to the head abbot revealing Dillon’s history. He was barred from ordination on the grounds of his “third sex.”

After this stinging rejection, Dillon connected with the growing community of exiled Tibetan monks in Sarnath. One incarnate lama in particular, Denma Locho Rinpoche, was empathetic to Dillon’s situation, believing that his sex did not necessarily violate Vajrayana interpretations of the Vinaya laws. Locho Rinpoche ordained Dillon in 1960; Dillon made his way to Ladakh soon after, where entered a remote monastery called Rizong Gompa.

Yet another first, buried at the tail end of his biography: Dillon was the first Westerner to be ordained as a getsul, a novice monk in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. He spent his final years in Ladakh’s mountains and the Himalayan foothills, living alongside young Ladakhi monks, with the new name of Lobzang Jivaka. Yet Dillon’s spiritual awakening was short-lived; in 1962, two years after entering Rizong, Dillon died unexpectedly, alone at a hospital in Dalhousie, a hill station in Himachal Pradesh.

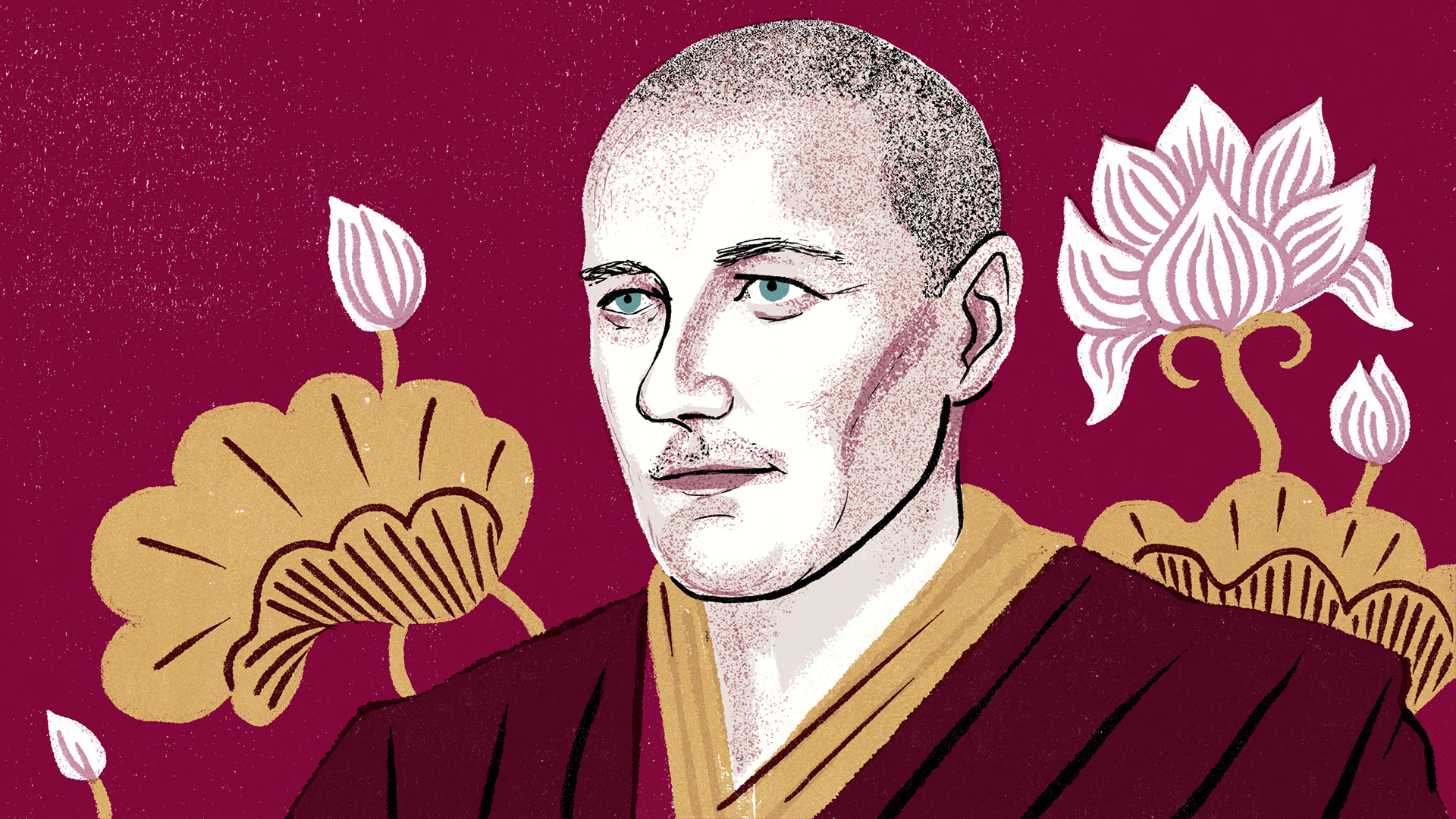

One image in that first Google search showed Dillon in his red monk’s robes, standing in front of tall alpine trees. The same face, but his head shaved, his beard gone, and his cheeks hollow. He gazes off with a glassy contentment in his eyes, glacier blue from colorization.

Why do I hold the image of that gaunt face in my mind when I take refuge, or make mandala offerings, or simply ask for guidance?

Michael Dillon was a very imperfect man. A product of his Edwardian upbringing, he held a colonial worldview that often flattened people and places into tropes and clichés. And perhaps the most painful truth of his life: He was so defensive against being “found out,” so profoundly shaped by the ways he had been othered, that he struggled to cultivate real intimacy or vulnerability with anyone. It is very possible, reading between the lines of his autobiography, journals, and publications, that he died without ever having kissed anyone. He wrote constantly of feeling as though other people were living, while he was watching. This permanent sense of separation shaped his brief forty-seven years of life.

Like so many living at the margins or in the cracks of society, Dillon traversed teachings, methods, and practices, his search continually adapting to both his rejection from religious institutions and the seeds of his own faith and awakening.

Dillon and I share simple biographical facts—we are both white transgender men, and both Western students and practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism. But even that description feels oddly formal, overly attached to labels, fixed positions, and doctrines. To simply call Michael Dillon a Tibetan Buddhist convert obscures the teachings contained in his meandering path. Like so many living at the margins or in the cracks of society, Dillon traversed teachings, methods, and practices, his search continually adapting to both his rejection from religious institutions and the seeds of his own faith and awakening.

I see myself in Dillon, for better and for worse. I see myself in that abiding sense of separation and remove. I also see myself in the essential questions, the yearnings and longings, which drove his restless search for something. It’s not clear to me that Dillon always knew what he was searching for. He used many words—belonging, completeness, the truth—to describe the ineffable, mysterious end point of his quest. In fact, he was fixated on endings, declaring them, undeclaring them, and redeclaring them constantly.

Dillon wrote the bulk of his autobiography, Out of the Ordinary: A Life of Gender and Spiritual Transitions, while at sea on merchant marine ships, in the hull of a vessel literally circumnavigating the globe (the book was finally published by Fordham University Press in 2016, expertly and lovingly edited by Jacob Lau and Cameron Partridge). A nascent interest in doctrines of reincarnation shaped the way he wrote about “the world he’d left behind,” his own memories loosely tethered together like scenes from a dream. The doctrine of rebirth seemed to offer him a new way of understanding his own propensity for fleeing and starting over.

Amidst the thicket of his judgments of self and other, the highly conditioned and acculturated ways he reduced people to markers, Dillon transmitted bursts of raw insight—into himself, into the culture that shaped him, into the limits of that Anglican imperial worldview. What I mean by this is that he, sometimes simultaneously, illustrated the limits of his conditioning and broke free of them.

Do any of us truly know what we are searching for? And, when we think there is an object at the end of our search, what is that object hiding, misnaming, or trying to contain?

We seek new cities, new countries, new families, new names, new bodies. We pursue external transformation, relocation, and the emptying out of an unbearable feeling. Buddhist philosophy—surely, the philosophy Dillon encountered and was changed by—proposes a new version of reality in which these externalities are merely phenomenal appearance, the shifting terrain of light, sound, and color, the background for the ultimate path toward liberation from selfhood.

Living as a man did not eradicate my yearning. Meditation alleviates it sometimes, and certainly helps me view it more clearly, particularly desire’s liquid ability to always seep into new objects and destinations. But neither manhood nor meditation has liberated me from the grasping that fuels suffering (Skt.: upadana). We have many frameworks for articulating the disappointments of desire, for the elusiveness of objects, states, or conditions we tell ourselves might bring us contentment. And yet there is a child in me who hoped that being a handsome man would bring my search to an end. Then, in the aftermath, there was the hope that Buddhism might do what manhood hadn’t. To no one’s surprise, and certainly not the dharma’s, neither has delivered me from suffering.

Do any of us truly know what we are searching for? And, when we think there is an object at the end of our search, what is that object hiding, misnaming, or trying to contain?

I often come back to my time in Folkestone, Dillon’s hometown. This was part of an ongoing pilgrimage, not rooted in the idea of an infallible guru, or a deity, or even the first in a lineage. This pilgrimage is about sangha, the third of the Buddha’s three jewels, after the Buddha himself and the dharma. Sangha exists across the three times and the ten directions, a link formed through and out of samsara.

It was from high on those bluffs in Folkestone that a young Dillon watched soldiers, barely older than he, board boats and set out for the Great War’s Western Front, amidst what was, at the time, the largest military event in human history. He was only just beginning to grasp the reality of death, vaguely aware that few of these young men would return home alive. Nor did he know that a young surgeon named Harold Gillies, stationed along the snaking trenches, was working with injured soldiers to develop the techniques he would someday use on Dillon. There was so much Dillon could not see, could not predict, from that cliff above the channel—an even greater, deadlier war; the decline of his country’s empire; the circumstances of his physical transmutation or his own death.

Years after leaving home, Dillon passed through the English Channel on a merchant marine ship, and saw Folkestone from the water. In his autobiography, he recalls waving up at the town’s bluffs, as if his child self was standing there looking back at him. The end holds only if we pretend there is no continuation, if we limit our perception to occlude whatever unknowable state exists on the other side. Perhaps this is Michael Dillon’s most potent offering—we start over, and return, and start over, and return again.

UsenB

UsenB

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=90ed771b68&c=1)