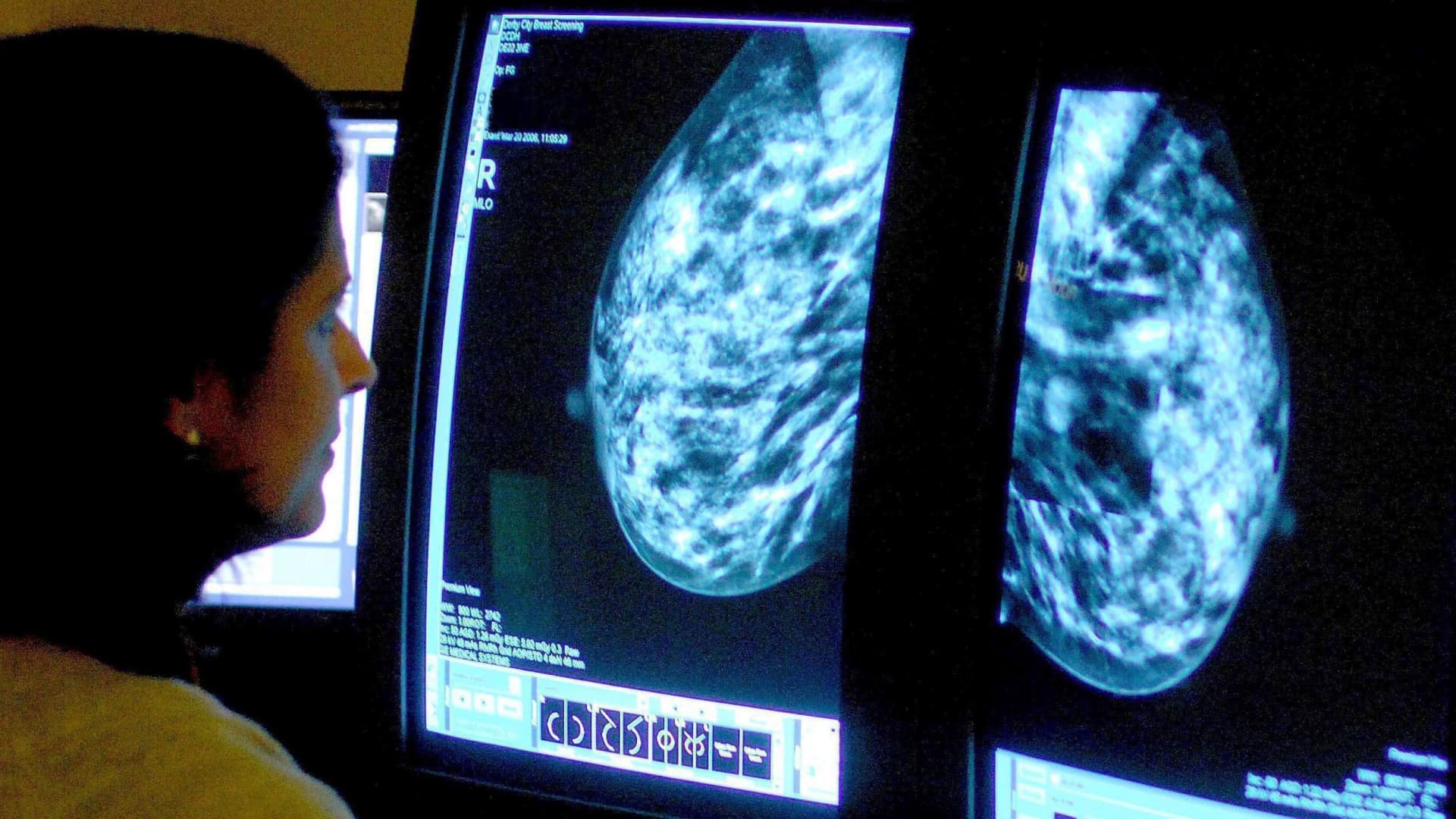

Scientists shed new light on how early stage breast cancer spreads to other organs

A team of scientists led by Mt. Sinai in New York City shed new light on how pre-malignant cells can spread from early breast cancer to other parts of the body.

A consultant analyzing a mammogram.

Rui Vieira | PA Wire | Getty Images

Scientists have shed new light on how early stage breast cancer spreads to other organs undetected, which can cause fatal metastatic cancer in some women years later.

Before a breast cancer tumor is even detected, cells that are not yet malignant can spread to other organs where they lie dormant and don't replicate, according to new research led by Maria Soledad Sosa, a professor at Mount Sinai's Tisch Cancer Institute in New York City.

The NR2F1 gene normally prevents pre-malignant cells from spreading to other parts of the body.

Sosa and a team of scientists found that a cancer gene, HER2, suppresses the NR2F1 gene, allowing pre-cancerous cells to move to other organs of the body where they can become cancerous.

"Evidence is suggesting that even before a primary tumor is detectable, you can have cells that disseminate also to secondary organs and they can eventually also form metastasis," Sosa said. The lungs, the bones and the brain are common places for breast cancer to metastasize, or spread.

The team's research was published Tuesday in the peer-reviewed journal Cancer Research. The lab study was conducted using samples of an early form of breast cancer known as ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS, as well as cancer lesions from mice.

Sosa, the study's lead author, said understanding the mechanism that allows the pre-malignant cells to spread throughout the body could one day help determine which women are at a higher risk for breast cancer relapse. If a patient is showing low levels of NR2F1, it could be a sign that dormant cancer cells are spreading in the body where they can reactivate later and cause disease.

The study's findings could have an impact on how women diagnosed with DCIS are treated. DCIS is an abnormal cell growth in the lining of the breast's milk duct that has not developed into a malignant tumor. DCIS is traditionally considered noninvasive, meaning the abnormal cells haven't spread yet. However, research by Sosa's team and others is challenging that notion.

More than 51,000 women in the U.S. will be diagnosed with DCIS this year, according to the American Cancer Society. Many women diagnosed with DCIS undergo either surgery or radiation or both. However, women diagnosed with DCIS who undergo these treatments still have about a 3% chance of dying from breast cancer 20 years after their diagnosis, according to a seminal study published in Jama Oncology in 2015.

More than 150 women in the study who had their breast removed still died from cancer, which means disease had likely spread at the time of detection. The scientists concluded that the classification of DCIS as noninvasive should be reconsidered, warning that some cases of the carcinoma have an inherent potential for distant spread to other parts of the body.

"Even though they do the surgery of DCIS or sometimes it's treated with radiotherapy, the mortality rate doesn't change. This is telling you that it doesn't matter what is there in your primary site," Sosa said. The problem is that the abnormal cells are spreading from the carcinoma, she said.

FrankLin

FrankLin