Self-Power and Other-Power

On the limits of pride and the humility of faith in Shin Buddhism The post Self-Power and Other-Power first appeared on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. The post Self-Power and Other-Power appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Let us now turn to our discussion of Other-power. Other-power is tariki in Japanese, and self-power is jiriki. The Pure Land school is known as the Other-power school because it teaches that tariki is most important in attaining birth in the Pure Land, whether understood as regeneration or enlightenment or salvation. Whatever name we may give to the end of our religious efforts, that end comes from Other-power, not from self-power. This is the contention of Shin Buddhists.

Other-power is opposed to what is known in Christian theology as synergism. This means that in the work of salvation a person must do his or her share just as much as God does his. In contrast to synergism, the Shin school may be characterized as monadism, which means working alone in the sense that Other-power works alone, without any self-power being involved. Salvation is all Amida’s work. The relative existence that we ordinary people lead has nothing to do with effecting our birth in the Pure Land. Birth in the Pure Land is none other than attaining supreme enlightenment.

What I term monadism, the singular working of Other-power, may be illustrated by the behavior of cats. When the mother cat carries her kittens, she grasps the neck of each kitten with her mouth and carries it from one place to another. That is monadism because the kittens just let their mother carry them. In contrast, monkeys carry their offspring on their backs. This means that the baby monkeys grasp their mother’s body with their limbs or tails, so the mother is not doing all the work by herself. The baby monkeys do their share. This is the way of synergism, in contrast to the way of monadism, illustrated by the behavior of cats.

In Shin teaching we can say that it is only by the power of Amida that our liberation and freedom are assured. We don’t add anything to Amida’s working. This doctrine of Other-power, or monadism, is based on the idea that humans are relative beings, and as long as we are so constituted, there is nothing in us that enables us to cross the stream of birth and death. Amida comes from the Other Shore, carries us on the ship of the Primal Vow, and delivers us onto the Other Shore.

A deep chasm exists between Amida and ourselves. We are so heavily burdened with karmic hindrances that we cannot shake them off by our own power. Amida must come and help us, extending the arms of help from the other side. This is what is generally taught by Shin people. But from another point of view, unless we exhaust everything we have in our efforts to reach the ultimate end, however ignorant and helpless, we will never be grasped in Amida’s arms.

It is all right to say that Other-power does everything by itself. We just let it accomplish its work. Nevertheless, we must become conscious of Other-power doing its work in us. Unless we are conscious of Amida’s doing work in us, we shall never be saved. We can never be sure of the fact that we are born in the Pure Land and have attained our enlightenment. To acquire this consciousness, we must exhaust our efforts. Amida may be standing and beckoning us to come to the Other Shore, but we cannot see Amida until we have done all we can do. Self-power is not what is really needed to cross the stream of birth and death, but Amida will extend his helping hand only when we realize that our self-power is of no account.

Since we cannot achieve the end of our endeavors on the path of enlightenment, Amida’s help must be recognized. We must become conscious of it. In fact, recognition comes only after we have strained all our efforts in crossing the stream by ourselves. We realize the inefficiency of self-power only when we try to make use of it and are made aware of its worthlessness. Other-power is all-important, but this truth is known only by those who have striven by means of self-power to attempt the impossible.

The realization of the worthlessness of self-power may also be Amida’s work. In fact, it is, but until we achieve self-awareness, we do not realize that Amida has been handling all this for us and in us. Therefore, striving is a prerequisite of any realization. Spiritually speaking, everything is finally from Amida, but we must always remember that we are relative beings. As such, we cannot understand things unless we first try to do our best on this plane of relativity. Crossing from the relative plane to the absolute plane of Other-power may be logically impossible, but it appears to be impossible only before we have tried everything on this plane.

We have been discussing self-power, the relative plane, devoted striving, and using up ourselves. These are all referring to the same thing, what is called in Japanese hakarai, “calculation.” This technical term, well-known to Shin people, is similar to the Christian notion of pride. Generally speaking, Christians do not use philosophical terms such as self-power and Other-power, but “pride” is none other than self-power. This pride is self-assertion, complimenting oneself as being worthy, someone who can accomplish great things. To rely on self-power is pride, and such pride is very difficult to uproot, as is the belief in self-power.

In our world of relativity our every action depends on self-power. On the moral plane, especially, we talk constantly about individual responsibility, personal choices, and decision-making—all products of self-power. As long as we live in a moral world, each person must be responsible for his or her actions. If we acted without any sense of responsibility, society would be really chaotic and fall into demise. Therefore, self-power, or pride, is needed in this normal world of relativity. This holds true as long as life proceeds smoothly, that is, without encountering any obstacles or anything that frustrates our ambitions and goals. But as soon as we encounter an obstruction in our path, we are forced to reflect upon ourselves and assess our powers.

Whether individuals are conscious or not, when we speak of society—whether a community, a congregation, or a gathering of any kind—each person has to become responsible to a greater or lesser degree if any meaningful solution is to be found.

Such obstructions in life may be enormous, not only individually but also collectively. As our society becomes more and more complex, the hindrances and obstructions become increasingly collective in nature and people feel less and less responsible for them. But whether individuals are conscious or not, when we speak of society—whether a community, a congregation, or a gathering of any kind—each person has to become responsible to a greater or lesser degree if any meaningful solution is to be found.

When we encounter difficult problems, we reflect upon ourselves and find that we are altogether impotent to overcome them. If we did not have any obstacles confronting us, things might proceed smoothly and safely. But the very moment we encounter an obstacle that seems insurmountable, we reflect and find our self-power completely inadequate to cope with the overwhelming difficulties. We then feel frustrated, and all kinds of anxiety, uncertainty, fear, and worry begin to multiply. Such feelings, in fact, characterize contemporary life. Pride is curbed at this point. It has to give way to something higher or stronger. Then pride is humiliated. In our relative world, on this plane of contingency, such obstacles are bound to appear as long as we live. They cannot be avoided.

Earlier Buddhists used to say, “Life is suffering, life is pain, and we are compelled to try to escape from it or transcend it, so that we are no longer shackled to birth and death.” They used such words as “emancipation, liberation, and escape.” Nowadays, instead of such terms we speak of attaining freedom or transcending the world.

This relative world is characterized by all kinds of strivings, and unless we strive we cannot get anything. But once we transcend relativity, striving, self-power, pride, and hakarai, no effort is expended. Self-power is replaced by Other-power, pride by humility. Hakarai is displaced by jinen-honi. In ordinary discourse the Japanese say, “Anata makase.” Anata means you, or thou, or the other. Makase, to use a Christian phrase, means “Let thy will be done.” Jinen-honi means, roughly, “entrusting oneself to Other-power,” and might also be rendered, “Let thy will be done.”

♦

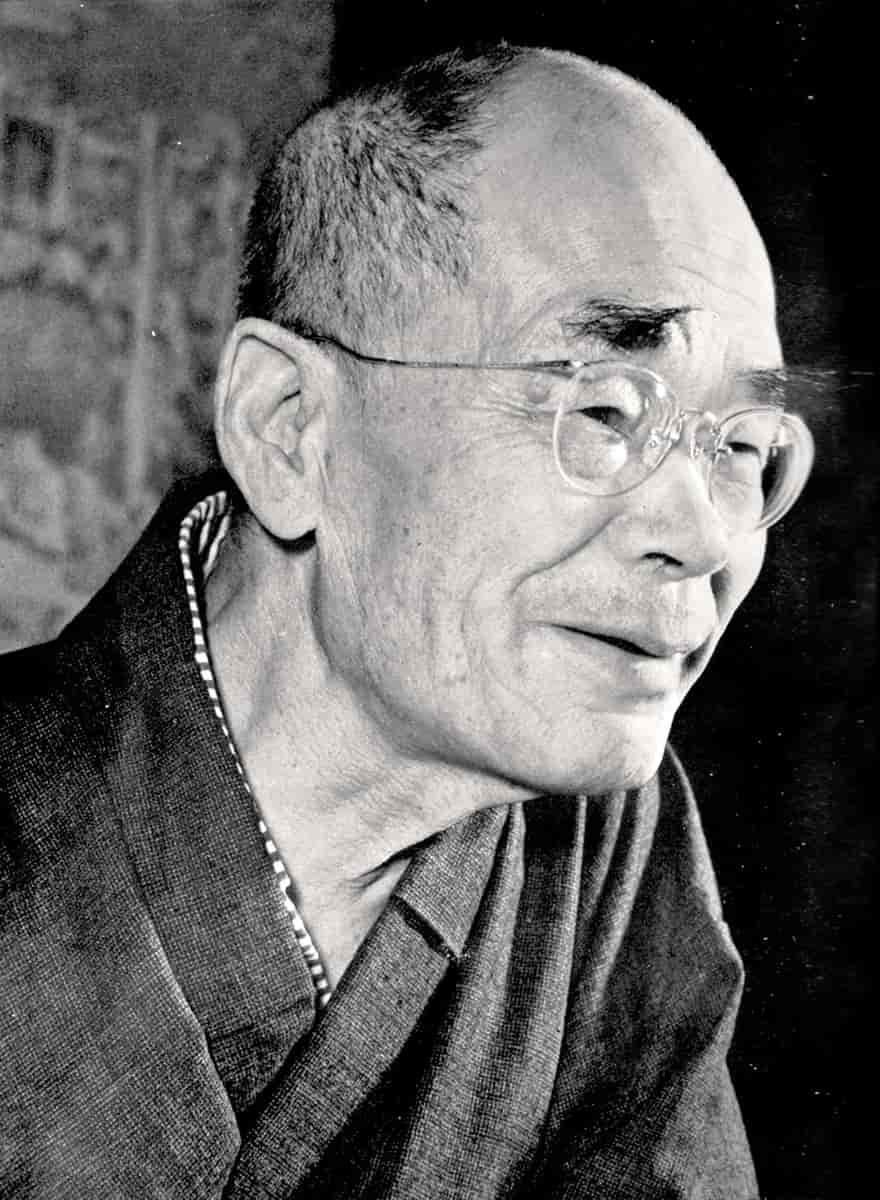

From Buddha of Infinite Light: The Teachings of Shin Buddhism, the Japanese Way of Wisdom and Compassion by D. T. Suzuki © 1998 by The American Buddhist Academy. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

KickT

KickT