Selling the Buddha

Restituting the Piprahwa relics to Buddhist custodianship The post Selling the Buddha appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

In May of this year, the auction house Sotheby’s postponed its Hong Kong sale of “gem relics” of the Buddha amid outrage from Buddhist leaders and scholars worldwide as well as a legal notice from the Indian government demanding their repatriation and a public apology. These relics were removed from a stupa (funerary monument) near the village of Piprahwa in northern India by the British colonial landowner William Claxton (W.C.) Peppé in 1898. The first credible find of remains of the historical Buddha in modern times, they are among the most well-studied Buddha relics in the world.

Now, two months after the auction was halted, the Indian government has announced that the Piprahwa relics have been purchased from the Peppé family by the Godrej Industries Group, an Indian chemical and agribusiness conglomerate headquartered in Mumbai, for an undisclosed amount. The Indian culture ministry hails it as “an exemplary case of public-private partnership” that ensures “the historic return of the sacred Piprahwa relics . . . to their rightful home in India.”

In an earlier op-ed and longer essay I wrote with SOAS University of London professor Ashley Thompson, we argued that the Sotheby’s sale commodified these sacred relics as private property to be bought and sold, furthering a legacy of colonial violence that transformed what was considered corporeal remains of the Buddha’s body into man-made “gems” appreciated only for their material value. Does this recent transaction correct the colonial wrongs that first tore these relics from their context in Buddhist veneration?

While we should rightly celebrate their return to India, it appears that the relics have exchanged hands only under private ownership, with Godrej Industries serving as their new owner. An instructive contrast can be made with the Buddhist relics from Sanchi returned by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum to India in 1947. In that case, then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru ceremoniously offered the relics to the Maha Bodhi Society, a Buddhist organization founded by Anagarika Dharmapala to revive Buddhism in India, which continues to make them available for worship annually. Godrej Industries, for its part, has reportedly committed to displaying the Piprahwa relics to the public for three months, and to loaning a “large portion” of the relics to the National Museum in New Delhi for five years. Beyond this, the long-term future of the relics remains uncertain.

With this announced sale, it may be a good time to take a step back to consider the significance of these relics from a Buddhist perspective. Has this all merely been a legal dispute over cultural heritage removed during the colonial period, like the Elgin Marbles, or the Indonesian artifacts recently returned by the Netherlands? And for Buddhists whose practice does not include the veneration of relics—or even Buddha images—what is the significance of these items?

Selling the Body of the Buddha

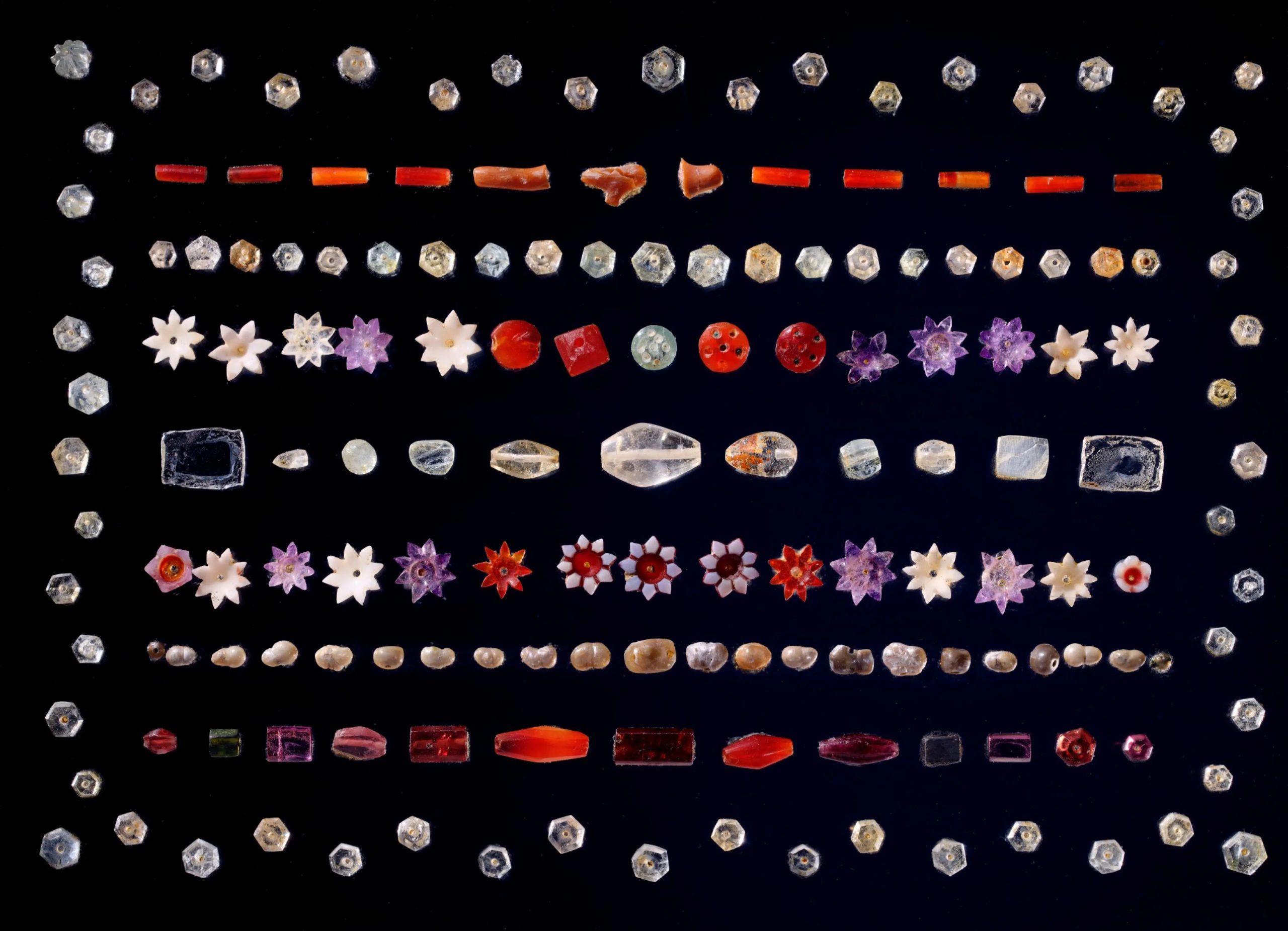

To the auctioneer, the relics appear to be gems or jewels—beads carved and shaped from natural materials like aquamarine, carnelian, and shell—and gold and silver sheet ornaments. Recent news coverage of the relics reiterates this identification, out of the need to provide readers with a straightforward answer to what they “are.” CNN and BBC journalists, for example, call them “dazzling jewels” and part of a “glittering hoard.” While such rhetoric may seem harmless, it reinforces the colonial designation of the relics as buried treasure, normalizing them as precious ornaments to be bought and sold.

When Peppé found the relics, the bone, gems, and ash were all mixed inside reliquaries secured within a large sandstone coffer—four of soapstone, one of crystal, and several of wood, which turned to dust upon contact with the outside air. Peppé emptied the reliquaries onto a table in his family home, sorting out gem from bone as he saw fit. Later, the British colonial government claimed the finds under the 1878 Indian Treasure Trove Act. Maintaining Peppé’s divisions, they gave the bone and ash to King Chulalongkorn of Siam (Thailand), and the gems to the Indian Museum in Calcutta (Kolkata). Peppé was permitted to keep a fifth of the gems. It is this portion of the Piprahwa relics that Godrej Industries has now purchased.

But this is where we must be careful about imposing our modern understandings, shaped by English translations of ancient Indian terms, on sacred Buddhist things. How did those who built the stupa at Piprahwa see the relics?

To answer this question, let us begin with the inscribed soapstone reliquary found in the stupa. Written in a local Prakrit dialect in Brahmi script, the inscription has been dated to 240–200 BCE, or more than 2,000 years ago. It has been read by many specialists, beginning with historian and colonial administrator Vincent A. Smith, with whom Peppé corresponded. Most recently, as documented in the 2013 National Geographic feature Bones of the Buddha, the philologist Harry Falk authoritatively translates the inscription as follows:

This enshrinement (nidana) of the corporeal remnants (sharira) of the Buddha of the Shakyas, the Lord, is to the credit of the Shakya brothers of the “highly famous,” together with their sisters, with their sons and wives.

Here, there is no distinction between gem and bone—all are sharira. Sharira, the word we imperfectly translate as “relic,” more precisely means “the body” or “bodies.” The other term usually translated as relic is “dhatu,” which means “essence” or “constituent element.” A Buddhist relic is therefore better understood as the essence distilled from the cremated Buddha’s body, which is why they are considered bodies of the Buddha in their own right. Relics enshrined in stupas were the legal equivalent of living persons in ancient South Asia, and owned not only the stonework of the stupa itself but also real property offered to it, like gardens with fruit trees. Buddhist textual scholars have observed that this is very different from the Christian understanding of the word “relic”—which derives from the Latin relinquere, “to leave behind”—as the fragments of what is left over from a dead body.

Hair Relics of Lord Buddha on display at the Gangaramaya Temple in Colombo. | Image via Wikimedia Commons

Hair Relics of Lord Buddha on display at the Gangaramaya Temple in Colombo. | Image via Wikimedia CommonsPrevious interpreters translated the Prakrit word nidana in the inscription as “container.” Falk, however, argues that nidana was more commonly used to refer to an “enshrinement,” the very act of depositing the relics inside the stupa. Instead of a simple label for this one relic container, it becomes a record of how two generations of the Shakya tribe jointly sponsored the entire stupa construction to enshrine Buddha relics. The Shakyas were members of the ruling clan of the ancient city of Kapilavastu, to which the historical Buddha himself belonged. That is why the Buddha is also called Shakyamuni, or “Sage of the Shakyas.”

What would such an “enshrinement” have looked like? We know from the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, a canonical account of the Buddha’s last days, that after the Buddha’s body had been cremated, people of the city honored the relics in their meeting hall for seven days “with dances, songs, music, garlands, and scents.” Later, the relics were divided into eight parts and distributed to eight tribes, including the Shakyas of Kapilavastu. The beneficiaries took their share of the relics back to their home cities, each building stupas and holding festivals to worship them. It is very likely that 300 years later, when descendants of the Shakya tribe reconsecrated a portion of the relics at the Piprahwa stupa, they did so as part of ritual festivities reminiscent of those mentioned in the sutta.

Imagine, then, the reverent hands of the Buddha’s descendants placing his relics in finely carved vessels. Holding parasols aloft to shade the reliquaries from the sun, they walk barefoot in procession around the stupa three times to the beat of drum and gong, as monks from the nearby vihara chant homage. Finally, the Shakya brothers and sisters, and their children, inter the relics deep within the stupa. On their lips, the fervent wish that the Buddha’s body be honored long after their own deaths, so that his teachings would last for 5,000 years. This sacred scene is a far cry from a colonial landowner and his family emptying boxes out on a table in a search for treasure.

In the Buddhist tradition, the line between bone and gem is not always clear. The Shakyas would have seen the “gems” as essences of their illustrious ancestor, perhaps produced from his cremated body. Buddhaghosa, a 5th-century Indian scholar, described how the sharira found in the Buddha’s cremation pyre were, as John Strong translated, “like jasmine buds, like washed pearls, and like [nuggets] of gold,” and in three sizes “as big as mustard seeds, as broken grains of rice, and as split green peas.” Buddhists today still look for such gemlike sharira in the cremation pyre of acknowledged masters.

Some of the “gems” may also have been donations made by the Shakyas to the Buddha at this moment of reconsecration. However, the donors would not have seen these devotional offerings as mere objects. They could have been intended to adorn the bone, as one would clasp a pendant around the bare neck of a loved one’s corpse. They were substitutes for the bodies of their donors, meant to remain in the presence of the Buddha’s remains in the stupa, making merit for them continually. More importantly, at the ritual moment of enshrinement (nidana), any distinction between “offering” and “relic” is effaced—all are now Buddha sharira.

What Is Custodianship?

My own encounter with the Piprahwa relics was in 2022, when I was the curator overseeing Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu art at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. We borrowed the relics for the exhibition Body and Spirit: The Human Body in Thought and Practice, which was part of the museum’s recent efforts to engage more meaningfully with local religious communities. A nearby Portuguese Catholic church lent us a silver chalice for celebrating the sacrament of the Holy Communion, and from a local mosque we borrowed drums they had used in the past to sound the call to prayer.

As I watched how reverently visitors approached the Buddha relics, however, it became clear that the relics strained the limits of what an art museum could meaningfully contain. People came to meditate in their presence on the last day they were on display. Looking back, I can only acknowledge my complicity with the museum in the ongoing commodification, with beginnings in the colonial period, of these sacred relics into art objects of merely antiquarian interest. What would custodianship attentive to Buddhist understandings of relics look like?

Buddha’s Tooth in the 10,000 Buddha Relics Collection. | Image via Wikimedia Commons

Buddha’s Tooth in the 10,000 Buddha Relics Collection. | Image via Wikimedia CommonsIn the last seven years, before their intention to sell the relics came to light, the Peppés traveled around the world to exhibit them in museums. After Singapore, the relics were brought to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, their most prestigious venue yet. After the exhibition at the Met ended in 2023, the Sotheby’s sale was announced, with a starting bid of HK$100m (US $12.8 million). Chris Peppé has stated that the family decided that an auction “was the fairest and most transparent way to transfer these relics to Buddhists.” But in a Sotheby’s auction, the lot goes to the highest bidder, whatever their religion. The winning bidder is rarely made public. Often, like the Salvator Mundi painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and sold at Christie’s New York for $450.3 million in 2017, the piece fades from public view. Incredibly, Sotheby’s continues to characterize their actions as part of a search to “identify the best possible custodian for the gems.”

That narrative is laid out in Chris Peppé’s essay for the Sotheby’s sales catalog titled “A Four Generation Story of Custodianship.” He and two cousins had inherited the relics in 2013 from their uncle Neil, who by his own account had thought of them simply as family curios kept in a cabinet in his sitting room. In the legal notice issued to Sotheby’s, India challenged this custodial claim, arguing that because it was the Government of India (then under British rule) that granted the custodianship to W. C. Peppé, it is they who have the “right of first refusal” since Peppé’s descendants wish to relinquish that role.

India contended that “custodianship would include not just safe upkeep but also an unflinching sentiment of veneration towards these relics.” A custodian’s role is an active one, with the obligation to make the relics regularly available for veneration, which is beyond the scope of most secular museums. To illustrate this, at the same time the Piprahwa relics were behind glass in Sotheby’s Hong Kong showroom, another set of Buddhist relics were invited to Vietnam from May 2 to May 25 for the 2025 United Nations Vesak Festival. Excavated from the Mirpur Khas stupa in Sindh (now in southern Pakistan) in 1910 by the Archaeological Survey of India, these relics were gifted to the Maha Bodhi Society of India in 1934, which reenshrined them in a new Buddhist temple built in Sarnath, the site of the Buddha’s first sermon.

The verb “to invite” is used deliberately for the relics in the Vietnamese government’s press release—they are not objects to be taken and transported against their will but living beings whose permission must be respectfully sought to travel. This year, representatives from the Maha Bodhi Society of India escorted the relics to the National Museum in New Delhi, before inviting them onto a military airplane to Vietnam, where they were welcomed in a ceremony and honored with a parade. Then, at each of the four Buddhist pagodas they visited throughout Vietnam, the relics were enshrined by ritual specialists for visitors to worship. Custodianship here required knowledge in the proper etiquette and protocols for behaving with the relics, as well as the expertise to conduct the appropriate rituals and ceremonies of enshrinement at each pagoda.

Relics like the ones found at Piprahwa, in making the Buddha present, are the seeds from which living Buddhist communities can grow.

In the same vein, the British Maha Bodhi Society, in a May 6 letter shared with me, advised Sotheby’s to “meritoriously offer these gems to the custodianship of a renowned Buddhist organization, one that is trustworthy and experienced in enshrining the Buddha’s relics, so that they may be venerated for generations to come.” For them, it is important that future enshrinements of the relics are “performed in accordance with centuries-old traditions”—traditions that may be traced to those performed by the Shakya clan at the stupa they built at Piprahwa.

What has become clear to me is that relics like the ones found at Piprahwa, in making the Buddha present, are the seeds from which living Buddhist communities can grow. Ceremonies of enshrinement of the relics not only help us make merit for well-being in this life and the next but also are simultaneously ritual performances of relationships spanning space and time. Think of the diplomatic triumph of eight tribes in ancient South Asia agreeing to share the Buddha’s relics to honor his teaching of forbearance (khanti), or the Shakya clanspeople reaffirming their connection to their revered ancestor. There is an emotional resonance in Buddha relics, such that Buddhists feel pain at their abuse. To take the Piprahwa gems out of the cycle of commodification and to restore them to Buddhist custodianship would be an act of healing, enabling them to nurture future moments of connection for Buddhist communities.

Is India, together with Godrej Industries, willing to collaborate with Buddhist organizations in Asia to create an equitable model of custodianship for the Piprahwa relics, one that makes them accessible for veneration across national borders? The relics landed in India on July 30, and there are plans to formally unveil them to the public in a special ceremony. But the physical repatriation of any object to its geographic area of origin is only the beginning of the work of restitution, which must attend to the people for whom the object holds meaning. “India’s close association with Bhagwan Buddha and his noble teachings”—as Prime Minister Narendra Modi put it in his celebration of this return—will be truly honored only by restituting the relics, materially and spiritually, to the global Buddhist community.

JimMin

JimMin

![We’re Bringing The SEJ Newsroom To You, Live [Free Event] via @sejournal, @hethr_campbell](https://cdn.searchenginejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/sej-live-ap-2-974.png)