Shinran’s Engaged Buddhism

Religious scholar Jeff Wilson explains how the radical teachings of Shinran Shonin, the founder of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, can help us navigate today’s social and environmental problems. The post Shinran’s Engaged Buddhism appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

We really could use someone to look up to these days.

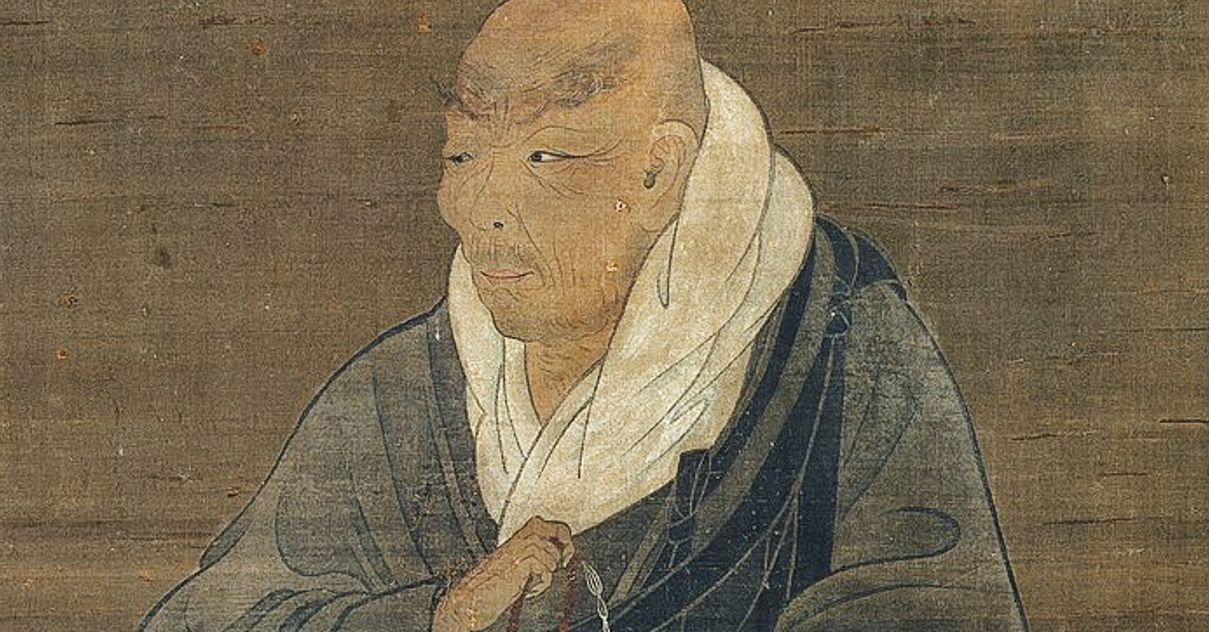

In Living Nembutsu: Applying Shinran’s Radically Engaged Buddhism in Life and Society, religious scholar Jeff Wilson presents us with a radical role model: Shinran Shonin (1173–1263). Shinran, who founded the Jodo Shinshu school of Pure Land Buddhism, lived during a time of social, political, and religious upheaval in medieval Japan, a time that produced fellow radical religious thinkers like Honen, who first advocated for chanting the nembutsu, and Nichiren. By rejecting mainstream Buddhism, with corrupt monks and monasteries, Shinran worked to create a Buddhism that was available to everyone regardless of their social and economic standing; all one has to do is put their faith in Amida Buddha and call his name to be born in the Pure Land.

Living Nembutsu, published in March 2023 by Sumeru Press, includes chapters called “Queer Shinran” and “Refugee Shinran,” and explains how engaged Shin Buddhism and Shinran himself can inspire Pure Land practitioners and help us navigate today’s most pressing issues. Wilson, a Tricycle contributing editor, is professor of religious studies and East Asian studies for Renison University College at the University of Waterloo (Canada) and an ordained Jodo Shinshu minister. He recently spoke with Tricycle about how “radical Shinran” worked within the Buddhist tradition to once again make Buddhism’s liberatory potential available to everyone.

What’s the story on how this book came to be? The project has been percolating for a long time. Jodo Shinshu has been my primary community of practice for the last twenty-five years or so. I went to graduate school and became a professor of Buddhism, and eventually I got ordained—I serve in a supporting ministerial role at the Toronto temple. And as part of all that, I’ve been asked to give dharma talks and participate in seminars for the past twenty years. When you’re a speaker, you talk about the things that you’re interested in, but people also start asking you things that you eventually start incorporating into your talks. And one thing that often comes up is the intersection of Buddhism and various social issues—the hot topics of the day.

A lot of people wondered about the role of Jodo Shinshu in social, political, and environmental issues. There is a stereotype that Pure Land Buddhism has been passive, not engaged. I’m a historian and anthropologist in addition to being a practitioner, so from my research I know that actually many people, both historically and currently, have been involved.

Shinran himself was very involved in the social issues of the day. We think of him as a religious reformer, but 800 years ago in Japan and everywhere else on the planet, there was no separation between the religious and secular. And Shinran was politically persecuted because he was teaching what we today might call a Buddhist liberation theology. If you’re trying to liberate people from the oppressive social order through religious means, the powers that be are not going to take kindly to that. He was a political prisoner, exile, and refugee. And so I thought, this is easily the most important single monk in Japanese history, the cultural impact of his teaching is larger than anyone else, his movement is the largest and has been deeply involved in politics for over 800 years. So why do we keep asking these questions about whether Jodo Shinshu has a history of social engagement?

Religious scholar Jeff Wilson

Religious scholar Jeff WilsonHow did you first encounter Shinran: as an academic or practitioner? I first read Dr. Alfred Bloom’s book Shinran’s Gospel of Pure Grace (first published in 1965) in the mid-nineties when I was studying at Sarah Lawrence College. It was interesting, different, not at all like the other stuff about Buddhism I was reading in English at the time. And the “gospel of pure grace” seemed so Christian … he had to work within the language constraints of the time, when religious studies in North America were dominated by the study of Christianity. I was attending all sorts of different groups: Zen, Shambhala, Insight, in order to broaden my understanding of Buddhism to the greatest extent. And I started to steer more into Jodo Shinshu, especially as I became disillusioned with my time with Zen Buddhism. It wasn’t that Zen was bad; it had a tendency to pump up my own ego—the better I got at meditation or keeping the precepts or the more I could talk intelligently about koans, the more self-conceited I started to get. It wasn’t a good match. I was also concerned about how few Asian practitioners there were in many of these spaces. And then I began attending the New York Buddhist Church on the Upper West Side, and became more and more drawn in until Jodo Shinshu became the tradition that I was adopted by.

What was going on in Japan during Shinran’s lifetime that led him to such radical thinking? What I’ve tried to convey in my talks at Jodo Shinshu temples and in other situations is just how radical Shinran was. Jodo Shinshu grew to become the largest Buddhist school in Japan—one out of every three Japanese people’s family background is Jodo Shinshu—it’s all kind of very normal (at this point). I wanted to convey the really unique things about Shinran.

Shinran was born into an ossified medieval social hierarchy, where Buddhism’s revolutionary potential was profoundly muted by social conditions that put the dharma and Buddhist practice out of the reach of all but the most privileged. Japan was wracked by constant civil war, environmental disasters, epidemics, the threat of foreign invasion, elite Buddhist monastic complexes that hoarded their power with armed monks, and a vast gulf between the lives of the enfranchised and the great mass of poor regular people. The old style of Buddhism, including the Tendai school he was trained in, was beautiful and true but no longer relevant. Worse yet, establishment Buddhism had become one of the primary obstacles between average people and Buddhahood. Shinran wanted to create a Buddhism focused on freeing those who had been excluded from the current Buddhism.

“Shinran drew on his own suffering, exile, downward mobility, and outlaw status to build a true solidarity with the people of Japan.”

Buddhism for the 99 percent. That’s right. Shinran turned to the Pure Land teaching of Honen (1133–1212), another radical monk, as a solution. Honen created a revolutionary sangha, sort of like a Pure Land ashram where men and women, monastics and laypeople, upper class and lower class all mingled freely as practitioners of the nembutsu. Their flouting of strict social standards that were designed to keep everyone in their carefully ordered place, and their insistence that the expensive and esoteric rituals of elite Buddhism were unnecessary due to the liberating power of Amida Buddha, earned them the enmity of the powerful monasteries. Honen and Shinran’s community was smashed and their Pure Land Buddhist teaching was made illegal. They were exiled as criminals, their ordination stripped by official censure. In those days, conditions in Kyoto were relatively better, and Shinran was thrown out into the “real” Japan. He was living among the peasants and fisherpeople, and this reinforced his idea that “these are the people that the Buddha cares about but that elite Buddhism doesn’t care about.”

This unjust persecution helped to truly set Shinran free. It was clear to him that the powers that be would never support a Buddhism of universal liberation, regardless of their supposed commitment to Mahayana Buddhism. And with nothing left to lose, Shinran turned fully to preaching a Buddhism he felt was designed for his times. He drew on his own suffering, exile, downward mobility, and outlaw status to build a true solidarity with the people of Japan. He did so by teaching in the vernacular, offering dharma lessons that could be distributed and read out loud at gatherings for the benefit of the illiterate majority. He composed dharma hymns that could be memorized and performed in meetings or individually, without the need for scriptural study. He told the farmers, soldiers, and women who came to listen to him that there was a path designed for them, in their ordinary, toiling, oppressed lives, one that didn’t demand expensive dana payments, unrealistic moral precepts, or rejection of the family and community ties without which life was literally impossible in regular society. And he demonstrated this by eating meat, drinking alcohol, marrying, and raising a family, while still fulfilling the role of a monk through teaching, wearing robes, and performing rituals.

You write that Shinran transformed Buddhism by working within the existing framework, but it just seems to me that he was doing something completely different! If you take a look at The Collected Works of Shinran, which is a massive, two-volume set, and start reading through it, you’ll see he does a lot of proof texting and quoting from other sutras, and you might think to yourself, “oh, this guy is super traditional.”

He didn’t advocate abandoning the classic texts, nor did he critique the famous teachers. He used their words, images, and ideas constantly in his own preaching, but he reinvigorated them with readings and meanings that teased out the fundamental principle of Amida’s Buddha’s compassionate liberation of all beings, which he felt underlay all Buddhism. He continued to use the resources his forebears had preserved and transmitted to him—Amida Buddha, the Pure Land, the nembutsu, the Primal Vow, the way of the bodhisattva—but he ensured their continued vitality by applying them in different, sometimes opposite, ways from their uses in the past, so that they met the needs of the suffering disenfranchised classes rather than insisting those with the least agency somehow overhaul themselves according to demands of unobtainable social positions or ancient cultures impossibly distant from their own. He was comfortable talking about Amida, the Pure Land, and other aspects of Buddhism with literal, symbolic, and pedagogic approaches according to the needs of his listener, and inhabited all of these modes as a person liberated from the boundaries and boxes that society wished to impose and enforce.

This method of respect for the past, combined with attention to the needs of the present, remains an important model for Jodo Shinshu temples today. Our times and places are not those of Shinran any more than Shinran’s were those of Shakyamuni Buddha, so we have to navigate the breathtaking pace of social and technological change and find ways to keep the dharma stream flowing as a genuine source of life and support. And we have to avoid succumbing to the modern Western temptation to simply throw away the old and entrust in the salvific power of the latest cool thing. We’re fortunate to have a guide like Shinran, who showed how to focus on what truly matters: the liberation of all people, not as a theory but as a way of living together in inclusive sanghas that can transform suffering into gratitude and joy.

The book focuses on modern Jodo Shinshu communities and how they’ve served LGBTQ communities, among others. Can you talk a little bit about projects in your sangha? My temple is involved in refugee assistance, and an important previous minister, Rev. Newton Ishiura—this was before my time—was quite involved in Indigenous matters, helping First Nations and Inuit people push for rights in Canadian society. And over the last dozen years or so there’s been a growing push within Jodo Shinshu communities in North America and Hawaii to become educated and sensitive on LGBTQ+ inclusion.

Jodo Shinshu is sangha-based, it’s not an individualistic, solo-meditator type of Buddhism. It’s family Buddhism, and so if someone comes out to their temple, they’re also coming out to their parents, aunties, grandparents, best friends—if you have difficulty being out to your family, you can’t be out at temple, because it’s the same people. We’re trying to highlight how Buddhism is supportive of LGBTQ+ people and that they’re an important part of the sangha. The nembutsu is precisely for those people whom our culture has labeled “evil” in the first place; when there’s more suffering, that is where Amida Buddha is rushing to. And if we can make our temples an inclusive, affirming, and empowering place, this will flow out to other places as well. Making it OK to be out as yourself at temple can then make it OK to be out at home, at work, on the street, etc.

“We’re fortunate to have a guide like Shinran, who showed how to focus on what truly matters: the liberation of all people.”

We have various LGBTQ+ affinity groups in some of the temples. Gardena Buddhist Church’s Ichi-Mi group just released a video called “A Profound Silence” that interviews various queer people and their allies about their experience as Buddhists and some of the challenges they face.

This doesn’t mean that these spaces were always inclusive, not because there were reasons in Buddhism for noninclusivity but because people didn’t understand how to be inclusive. From both Japanese and North American culture we’ve inherited degrees of homophobia, sexism, racism, and other challenges that we’re working to eliminate so that we can fulfill the central vision of Pure Land Buddhism: a harmonious, inclusive, welcoming sangha that serves as an engine for liberation.

Organized religion is on the decline in favor of more individualistic forms of practice. Is this the case in Jodo Shinshu communities in North America? And how might Shinran’s message of acceptance and the community’s embrace of often-marginalized groups—like the LGBTQ+ community and immigrants—help keep a congregation strong and connected? Yes, many Jodo Shinshu temples have experienced a contraction in the past generation, just as other religious institutions have. Within all areas of life, our society is undergoing a profound shift from smaller, closely interconnected, local and intimate relationships to larger, loosely interconnected, dispersed networks. Of course that comes with all the advantages and drawbacks—such as freedom and loneliness—that result from such an unprecedented and rapid cultural change.

Those changes represent challenges and opportunities for Jodo Shinshu temples. We’re subject to the same socially corrosive, centrifugal forces as everyone else. But within and between our temples we have an inherently resilient web of intergenerational bonds which helps to mitigate those forces to some degree. Now we need to continue to foster awareness of and continue to activate the radical welcome at the heart of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism.

As Shinran declares:

In reflecting on the great ocean of shinjin (the awakened, trusting heart), I realize that there is no discrimination between noble and humble or monks and laypeople, no differentiation between men and women, old and young. The amount of evil one has committed isn’t considered; the duration of religious practices is of no concern. It is a matter of neither practice nor good acts, neither sudden nor gradual attainment, neither meditative nor non-meditative practice, neither right nor wrong contemplation, neither thought nor no-thought, neither daily life nor the moment of death, neither many-calling (of mantras) nor once-calling. It is simply shinjin that is inconceivable, inexplicable, and indescribable. It is like the medicine that eradicates all poisons. The medicine of the Tathagata’s Vow destroys the poisons of our wisdom and foolishness.

Shinran is saying here that Amida Buddha’s vow of universal liberation is a great warm ocean that floats all of us, no matter who we are or what we’ve done. It breaks down all distinctions we erect between our group and so-called others (our “wisdom,” which the Buddha reveals to be foolishness) and accepts everyone just as they are. Our sanghas are called to be part of this great ocean of shinjin, of total acceptance and embrace. The point isn’t to build membership numbers, but naturally when you do have a community that can welcome in those who aren’t given welcome elsewhere, and where people of whatever type feel supported and connected, that will be a place that people want to be. So if we live up to our central religious principles of inclusion and acceptance, that will have a positive effect on keeping the sangha healthy and continuing as an institution that is valued by the community.

A thread throughout the book is Shinran inverting a teaching to make it clearer, and something you wrote in your chapter on the environment really struck me: the Earth is sick without us. Can you speak about this? Some of this comes from the Buddhist experience, but other perspectives as well, such as Indigenous issues in the US and Canada and the Landback movement. There is this idea of nature with a capital “N” as something pristine that we are spoiling. This is a romantic fantasy based on European enlightenment ideas; it has literally never existed.

And today, whether it’s about the rainforest or whatever is looking bad, we’re like, “oh no, poor Nature.” Even that creates an us and them situation. Everywhere you go, the Amazon, on top of mountains, and in caves and the deserts—there are people living there, and there have always been people living there. This idea that we’re destroying nature is a mental mistake, like when we draw a line around our skin and say, “this is me,” and beyond my skin is not me. Some people talk about getting rid of humans, like we’re a cancer or something. What we need is to slow down and develop a better relationship, better balance, so we stop destroying this thing that we ourselves are a part of. Shinran talks about the ability of the ocean to accept and purify even the most polluted rivers: it’s a metaphor for how Amida Buddha naturally transforms all beings into awakening. The Earth really does have amazing regenerative abilities, but we’re selfishly outstripping its capacity to handle our activities. We need to remember that our presence is part of what makes the land and water healthy, and lean into that role rather than ignorantly treating it all as “natural resources.”

This attitude is developed by the EcoSangha movement in the mainland Jodo Shinshu temples, and the Green Hongwanji program in the Hawaiian temples. And we saw an example of this at the Jodo Shinshu temple in Winnipeg. They inducted an elm tree as a member of the temple. It’s a small act but a significant one: it recognizes that trees are part of the sangha with us and that we support one another. It’s a reflection of the Pure Land, which is described as a beautiful place where people, birds, trees, and waters all live in harmony and enable one another’s awakening. That’s the vision that animates our temples, and we need to apply it in all areas of life.

♦

AbJimroe

AbJimroe