Maitreya in Outer Space

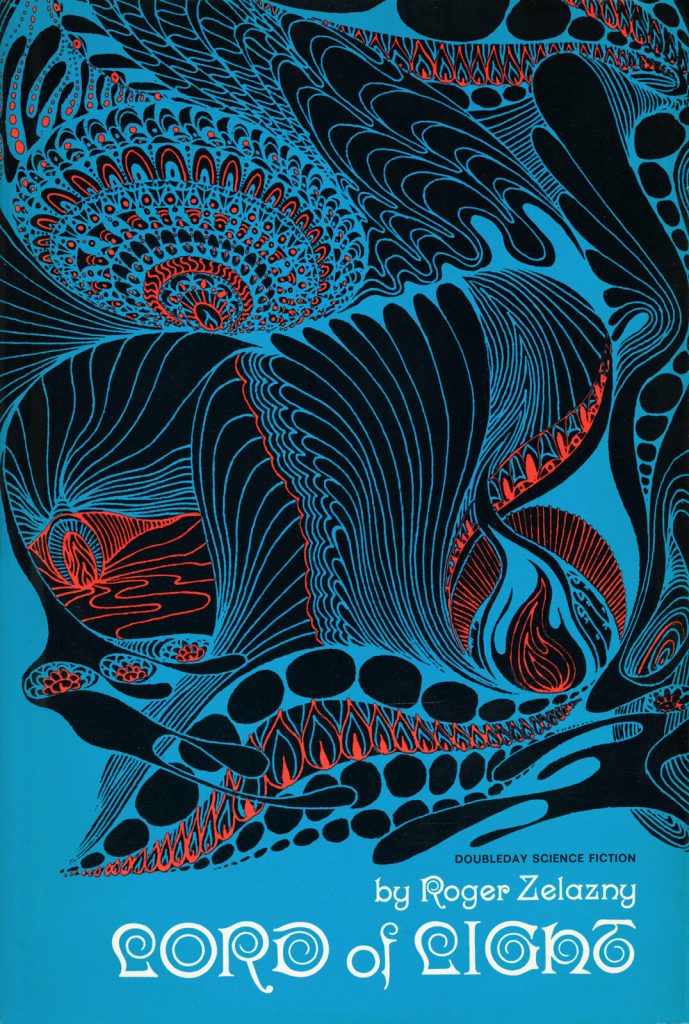

Roger Zelazny’s 60s sci-fi epic, Lord of Light, pits the Buddha against the Hindu pantheon on a distant planet The post Maitreya in Outer Space appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Roger Zelazny’s 60s sci-fi epic, Lord of Light, pits the Buddha against the Hindu pantheon on a distant planet

By Philip Ryan Apr 27, 2023

The action of Roger Zelazny’s Hugo Award-winning 1967 novel Lord of Light may be familiar to Buddhist readers—the rise of Buddhism in a Vedic or Hindu context—but the setting certainly is not. The book depicts the newly awakened Buddha on an alien world fighting against gods named Vishnu, Mara, Brahma, and Kali. The fight is not metaphorical, it’s a real battle in which the Buddha leads an army of zombies and demons in an effort to destroy “Heaven,” the Olympus-like home of the gods. Also in the fight are spaceships and giant lizards known as slizzards that are “much faster than horses.”

The book’s title refers to Maitreya, as several characters refer to the Buddha throughout, though he refers to himself most often as Sam, short for Mahasamatman. With this title Zelazny is likely thinking of Amitabha, whose name is often translated as “Infinite Light,” rather than Maitreya, whose name is related to “maitri,” or metta, meaning lovingkindness or friendliness.

Zelazny’s gods began as humans who traveled from Earth in a spaceship called the Star of India and subjugated an unnamed planet, naming its inhabitants—flamelike entities capable of possessing humans—rakshasas, or demons. The human conquerors, referred to as the First, assumed the identities of Indian gods, instituted a caste-bound society for new generations of humans, and created technology to mimic supernatural powers.

Reincarnation is also accomplished by technological means. The oldest and most important gods have been reincarnated twenty times or more, and their identities as humans have faded but never entirely disappear. The Buddha reveals that Brahma, the chief god, was originally a human named Madeleine, for example. Brahma now presents as male, but gender fluidity is a routine matter when undergoing reincarnation. When a god dies (and this happens frequently, often at the Buddha’s hand) a replacement must be promoted, and is free to decide their gender. Mysterious beings known as the Lords of Karma maintain a temple where petitioners can come and obtain new, younger selves—as long as the Lords’ “mind scan” judges them worthy of such a privilege. For those out of favor with the Lords, there are still “bootleg body shops” in out-of-the-way places that also offer rebirth. (It’s not clear where the bodies come from, whether they are grown in vats or taken from lower-caste people.)

The gods maintain a stranglehold on technology, keeping their subjects in a perpetually pre-industrial state, using swords and plows rather than guns and tractors. They demand prayers, which travel by way of radio waves, and for which special coin-operated machines are installed outside temples. Priests can directly address their deities using video screens (though the gods often don’t answer), and fancy gadgets abound for the elites, but efforts by ordinary humans to advance technology are condemned as “Accelerationism” and are viciously suppressed.

Into this world emerges the nobleman Siddhartha, also called Sam, who was one of the planet’s original conquerors. He lives a pleasant, undistinguished life until one day, angered by the prayer machines and the oppression of common people, he awakens and begins a planetwide rebellion. As Bernard Faure points out in 1,001 Lives of the Buddha, Zelazny in this work is influenced by Western ideas of the Buddha as a reformer of the caste system and proponent of progress. Buddhism and Accelerationism are fused into one movement, and the Buddha is heard to praise the virtues of ancient technology that the common people should be able to use.

After losing in his battle with the gods, the Buddha departs for “Nirvana,” a golden cloud of magnetized particles that surrounds the planet. But he is summoned back from this apparently blissful existence by the radio-wave prayers of Yama, the god of death, who operates a huge lotus-shaped satellite dish. The returned Buddha attempts to unwind or reverse his enlightenment, to become an ordinary person again: “He does not meditate, seeking within the object that which leads to release of the subject… He does study the object, considering its ways, in an effort to bind himself… He tries once more to wrap himself within the fabric of Maya, the illusion of the world.”

The gods are depicted as cynical and fraudulent, and the Buddha also describes himself this way, employing “the ancient words,” and “venerable tradition” to manipulate people. Yama says to him, “I know that you are a fraud. I know that you are not an Enlightened One. I realize that your doctrine is a thing which could have been remembered by any among the First. You chose to resurrect it, pretending to be its originator.” The Buddha replies, “Whatever the source, the message was pure, believe me. That is the only reason it took root and grew.”

But at other times the Buddha, and one of his disciples, an Angulimala-like figure who tried to kill the Buddha but was converted instead, are depicted as genuinely awakened:

“Summer passed. There was no doubt now that there were two who had received enlightenment: Tathagatha and his small disciple, Sugata. It was even said that Sugata was a healer, and that when his eyes shone strangely and the icy touch of his hands came upon a twisted limb, that limb grew straight again. It was said that a blind man’s vision had suddenly returned to him during one of Sugata’s sermons.”

The possibility of actual enlightenment spurs both the Buddha’s allies and enemies to action. “Enlightenment” throughout conflates Buddhist awakening and the Age of Reason. When one man awakens, the whole world is awake. The Buddha’s ability to understand and outwit the gods offers the only hope of defeating them, but in the process, instead of toppling religion and ending it, he creates a new one.

Roger Zelazny referred to himself as a lapsed Catholic and a man without a religion, but the topic reverberates through his works, including his ten-volume magnum opus, The Chronicles of Amber. All the religions appear in Lord of Light, if only briefly. A secret Christian, the chaplain of the original spaceship, inhabits the form of the Hindu death god/dess Nirriti, and fights against both the Buddha and the gods. Though the Buddha doesn’t ask it, his followers erect new temples and paint murals depicting his deeds. The ubiquity of gods and temples suggests that even in a time and place where science has solved the problem of mortality (if not morality,) religion is an inescapable part of human activity, despite its outward forms being imperfect or corrupt.

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Kass

Kass