Springtide Research Institute reports on mental health struggles among young Buddhists

Kevin Singer and Sam Ludlow-Broback report on the findings of Springtide Research Institute’s latest report Mental Health & Gen Z: What Educators Need to Know and what it reveals about young Buddhists facing mental health concerns. Young people of...

Kevin Singer and Sam Ludlow-Broback report on the findings of Springtide Research Institute’s latest report Mental Health & Gen Z: What Educators Need to Know and what it reveals about young Buddhists facing mental health concerns.

Photo by Julia M Cameron.

Young people of all backgrounds are facing a variety of pressures today. Many are expected to earn good grades and admission into a good college, pursue a meaningful career, save a dying planet, develop marketable skills, gain valuable life experience, and achieve some semblance of balance in the midst of it all.

All of these factors — on top of experiencing a multi-year global pandemic — have greatly impacted their mental health. A recent CDC survey discovered that 37% of U.S. high school students reported regular mental health struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic. These numbers have reached epidemic levels, pointing to a real crisis for today’s young people.

At Springtide Research Institute, we recently asked students in middle school, high school, and college (ages 13-25) about their experiences with mental health. Our latest report, Mental Health & Gen Z: What Educators Need to Know, features surveys and interviews with students of a variety of backgrounds, including young Buddhists.

A Complex Picture

Our survey findings from young Buddhists could be interpreted in several different ways. At first glance, one could conclude that they are experiencing mental health struggles at higher-than-average rates. About a third of young Buddhist students (35%) say they have been medicated or hospitalized for mental health issues (higher than the overall sample at 29%), while 46% have seen a mental health professional (higher than the overall sample at 41%).

However, these findings could also suggest that young Buddhists are more proactive about addressing their mental health struggles than their peers. For example, a little more than six-in-ten young Buddhists (64%) say that in the last three months, they have spoken with a mental health professional to receive help with emotional challenges. That’s significantly more than the overall sample at 49%. Moreover, 65% of young Buddhists have talked with a teacher or school staff member for help with emotional challenges over the last three months, an even larger gap above the overall sample of 41%.

It’s important that young Buddhists are taking these opportunities to talk to mental health professionals and adults at school, because they aren’t necessarily finding the same level of support at home from their parents. Six in ten (60%) young Buddhists agree, “My parents don’t take my mental health concerns seriously, compared to 45% of the overall sample, and 62% of young Buddhists agree, “I wouldn’t want my parents/guardians to know I was meeting with a school counselor/therapist,” compared to 48% of the overall sample.

There could be many reasons for this. Perhaps young Buddhist converts understand mental health in ways their parents, who are not Buddhist, don’t appreciate. Granted, we also find that young people today are not as committed to the religious practices of their parents or grandparents. Even if a young person’s parents are Buddhist, they might approach the topic of mental health differently.

Lonely At School

Of particular concern to us at Springtide is that 44% of young Buddhists tell us they are lonely at school – higher than the overall sample at 36%. It appears that while young Buddhists are seeking out help from adults like mental health professionals and teachers to help them navigate emotional challenges, they may not be experiencing a strong sense of belonging among their peers.

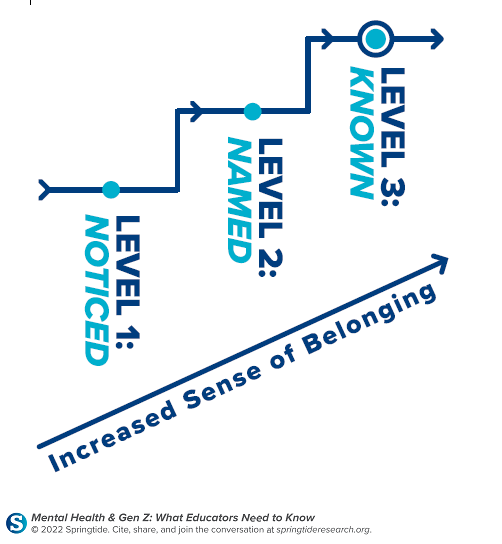

This is where teachers and other school staff can play a significant role. Springtide’s report outlines a three-step “belongingness process” that teachers and other school staff can implement that helps all students feel a sense of belonging and improved mental well-being.

The belongingness process promotes the importance of making young people feel noticed, named, and known.

Noticed, Named, Known

To feel noticed, young people want to be greeted. Adults at school can begin the belongingness process by acknowledging the presence of students and inviting them into certain spaces. Young people want to be accepted for who they are. This is a foundational element to the belongingness process, because without it, a deeper level of trust will never exist.

To feel named, young people crave a connection with people who remember them by name. In busy hallways or a packed classroom, being greeted by one’s preferred name is like an oasis in a desert. Naming students also can involve acknowledging a felt absence when they were gone, or by checking in on them with a simple email while they are sick or away.

Lastly, to feel known, there needs to be an even deeper relationship in which a young person feels safe being their full selves around peers and adults at school. After feeling noticed and named, feeling known includes the comfortability to be vulnerable, to discuss their mental wellbeing and to be confident that judgment will not result from the conversation.

Additionally, caring adults at school should recognize that a student’s religious or spiritual identity can be just as salient if not more salient than other identities. Half of students (49%) agree, “It would be important to me that a mental health counselor shares the same religious or spiritual beliefs as me,” while 41% agree, “The school mental health counselors do not share my religious or spiritual beliefs, so they might not understand me or the challenges I am having.” For students of all faiths and no faith, inviting them to discuss the role their religious or spiritual beliefs play in their lives as well as the role they might play toward improving their mental health could improve their sense of belonging at school.

The belongingness process is one that we are confident can improve a young person’s sense of worth and purpose, reduce their sense of loneliness, and enhance their mental well-being. It is a proactive, rather than reactive, way to deeply care about the mental health epidemic among students today. It can really change the lives of young people who have experienced deep disruption in their lives, and will provide them with a sense of home, support, and belonging.

Lynk

Lynk