Sun in a Sunless Place

A Buddhist scholar turns to Audre Lorde’s writings on embracing impermanence and living courageously in the face of death. The post Sun in a Sunless Place appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

At the age of 44, Audre Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer. It was 1978. Thus began a fifteen-year journey of living with chronic illness, the pain and insights of which she chronicled in two published journals and several essays. Lorde’s willingness to share the many epiphanies that arose during her healing process continue to inform my own understanding of how to turn toward the reality of impermanence, how to live passionately in the face of death, and how to privilege self-care in the midst of illness.

“There Is Nothing Stable Under Heaven”

Illness, for Audre Lorde, was an opportunity to see the reality of impermanence more clearly. She observed, and began to appreciate, the fact of constant change. As she reflected on impermanence, she acknowledged the reality of inevitable decay and death. “As a living creature I am part of two kinds of forces,” she wrote, “growth and decay, sprouting and withering, living and dying, and at any given moment of our lives, each one of us is actively located somewhere along a continuum between these two forces.”

The terror Lorde experienced at the prospect of dying led her to write evocatively of impermanence. Writing was a practice of self-soothing. “I am learning to live beyond fear by living through it,” she wrote in The Cancer Journals, “and in the process learning to turn fury at my own limitations into some more creative energy.” She further reflected: “As women, we were raised to fear. If I cannot banish fear completely, I can learn to count with it less. For then fear becomes not a tyrant against which I waste my energy fighting, but a companion, not particularly desirable, yet one whose knowledge can be useful.”

For Lorde, the fear brought on by the ultimate experience of impermanence fostered an unflappable state of mind that could be applied to any situation, including that of political aggression. If she could turn toward the inevitability of death, she could turn toward the militarized onslaught against Black people, women, and lesbian and gay persons suffering mass violence throughout the world. In The Cancer Journals, she wrote: “If I can look directly at my life and my death without flinching, I know there is nothing they can ever do to me again.”

Integrating Death into Living

Lorde’s confrontation with the fact of impermanence and death inspired a wellspring of insights. She still experienced anxiety, but confronting the fact of death furthered her capacity to embrace her fear and use it for growth and change. On November 19, 1979, she wrote: “There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it or giving into it.”

When Lorde was again diagnosed with cancer at age 50—this time with cancer of the liver—the prospect of impending death impacted every aspect of her consciousness. But rather than resist it or repress debilitating feelings of terror, she sought to embrace the reality of her diagnosis and to work skillfully with the feelings that arose. This process was emotional even as it was practical. She embraced meditation and relaxed movement exercises, as well as natural therapies and healthy food.

Acceptance of impermanence and its ultimate marker, death, became a daily work, a constant practice of attuning to her body and making wise choices of how to care for herself. It required a practice of training her mind; she acknowledged that denying death would only lead to more suffering. She wrote: “I must let this pain flow through me and pass on. If I resist or try to stop it, it will detonate inside me, shatter me, splatter my pieces against every wall and person I touch.” The intensity of her desire to relax into the fear and pain conveyed her strength. Pain and fear would not be the last words.

“There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it or giving into it.”

The will to work on behalf of women, Black people, and gay and lesbian persons throughout the world—she traveled to Germany, France, Switzerland, the West Indies, and different regions of the United States in the last years of her life—was a driving force for Lorde. At the same time, she turned toward the implications of her liver cancer. She felt that all of her pain and terror could be used for service and growth. On November 12, 1986, she reflected: “There is a terrible clarity that comes from living with cancer that can be empowering if we do not turn aside from it.” The “terrible clarity” expanded with a practice of accepting the fact of impending death, rather than pivoting from it.

That clarity and empowerment, for Lorde, was the awareness that even as she cared for her psyche and her body, she was most full of life when she surrounded herself with a community of loving women. She continued to assume her stance as a warrior. She wrote: “Battling racism and battling heterosexism and battling apartheid share the same urgency inside me as battling cancer.” The disproportionate violence and tragedy landing on Black women’s backs ignited in Lorde a sense of constant struggle. The presence of cancer also implied combat. This struggle was both personal and political. She could identify an enemy and saw herself as a warrior in a fight that was also in her body. The enemy was disguised as illness; it operated in her cells as well as in the broader world. Lorde mused:

How do I hold faith with sun in a sunless place? It is so hard not to counter this despair with a refusal to see. But I have to stay open and filtering no matter what’s coming at me, because that arms me in a particular Black woman’s way. When I’m open, I’m also less despairing. The more clearly I see what I’m up against, the more able I am to fight this process going on in my body that they’re calling liver cancer. And I am determined to fight it even when I am not sure of the terms of the battle nor the face of victory. I just know I must not surrender my body to others unless I completely understand and agree with what they think should be done to it. I’ve got to look at all of my options carefully, even the ones I find distasteful. I know I can broaden the definition of winning to the point where I can’t lose.

She approached her cancer in a way that was familiar to her: She turned toward the possibilities of inner and outer change, which, she acknowledged, were “not easy nor quick.” She acknowledged that she did not control many of the levers of her life. Nonetheless, she still possessed power: to choose how to meet the fact of pain, of death. She could not control the reality of cancer, but she could determine how to live passionately in the face of it.

This is also the message of the Buddhist teachings on impermanence. The fact that things end is a given, but as Lorde described, we can choose how to live in the midst of constant change.

Buddhism: The Five Remembrances

The Buddha taught that contemplating five subjects will help us to cultivate the path of wisdom and destroy obsessions. As the Upajjhatthana Sutta reminds us, we, as human beings, are subject to aging, illness, death, and separation. And lastly, we are the owners of our own actions. All beings are subject to these laws of nature. The Upajjhatthana Sutta continues:

Now, a disciple of the noble ones considers this: “I am not the only one subject to aging, who has not gone beyond aging. To the extent that there are beings—past and future, passing away and re-arising—all beings are subject to aging, have not gone beyond aging.” When he/she often reflects on this, the [factors of the] path take birth. He/she sticks with that path, develops it, cultivates it. As he/she . . . [does so], the fetters are abandoned, the obsessions destroyed.

Further, a disciple of the noble ones considers this: “I am not the only one subject to illness, who has not gone beyond illness.”. . . “I am not the only one subject to death, who has not gone beyond death.” . . . “I am not the only one who will grow different, separate from all that is dear and appealing to me.”

In my own practice, I leaned into the Five Remembrances, as they are known, as a path of wisdom. But I needed Audre Lorde’s voice, too, to remember that there was a broader view of illness, aging, and death. We are all subject to these laws. But sometimes illness descends too soon on some bodies that are seen as expendable by the broader culture. Lorde’s biographer Alexis Pauline Gumbs ponders this at great length. Did Audre get cancer because when she was 18 years old and broke, she worked in a factory and was exposed to radioactive material? And was this due to the fact that predominantly Black and Brown women were hired to work in this toxic setting?

Audre did not resist the fact of her illness and impending death. But she saw the burden of illness and death falling disproportionately on Black and Brown women. She named this pattern in apartheid South Africa as well as the United States. Old age, sickness, and death is inevitable for all of us. But some of us are considered expendable, and for us, old age, sickness, and death arrive too soon.

We have to protect ourselves, even as we seek to protect others, to balance stress with self-care and restoration. I heard this message in Audre’s reflections. It inspired me to rest.

“Caring for Myself Is Not Self-Indulgence, It Is Self-Preservation”

In the epilogue of her journals on living with liver cancer, Audre wrote:

I had to examine, in my dreams as well as in my immune-function tests, the devastating effects of overextension. Overextending is not stretching myself. I had to accept how difficult it is to monitor the difference. Necessary for me as cutting down on sugar. Crucial. Physically. Psychically. Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.

Lorde’s rawness as she grappled with the implications of her illness have inspired my own activism, and that of countless women I know who are asked to do too much. Even as we seek to confront violence and alleviate suffering, we are reminded of the need for balance and self-care. Many of the women in my life struggle with constant exhaustion and burnout. It is both a state of mind and a result of overwhelming conditions; we are constantly responding to the magnitude of what is coming at us.

In my own life, I have taken on enormous responsibilities, often with little or no support. And while I have not been diagnosed with cancer, I have lived with chronic illness, so much so that Audre’s words have resonated with me for more than two decades.

I remembered her wisdom when I underwent a life-threatening illness at the age of 35. I was parenting a one-year-old child and attempting to make my way through a doctoral program. The pressure was too much, literally. One afternoon after stepping off a flight following an academic conference, I noticed my head was throbbing. The pain was above my right ear. The following day, it had deepened into a migraine that did not go away. I stopped being able to eat or to sleep lying down. I saw doctors who could not help me. One day I managed to drive myself to the emergency room forty-five minutes away. The doctor gave me heavy painkillers and sent me home. But the migraine only deepened.

I stopped being able to speak clearly and could not swallow anything, even water. The next doctor I saw sent me to an Ear, Nose, and Throat specialist an hour away. This doctor put a camera down my throat and noticed that my soft palate and vocal cords were not moving correctly. He scheduled an MRI for that evening and admitted me to the hospital the next day.

“Two forces, growth and decay, sprouting and withering, living and dying,” Audre wrote. I was decaying, withering, dying. The MRI results showed a five-inch blood clot that had formed next to my brain and was moving toward my chest. It had damaged my vagus nerve, which runs the length of the human torso. This damage, in turn, had partially paralyzed my voice box and soft palate. It was the reason I could not speak or eat.

The only good news from the diagnosis was that the clot had formed in a vein instead of an artery. If it had formed in an artery, I would have had a stroke, and likely permanent brain damage.

Every day was an act of grappling with severe physical pain and trying to not succumb to the terror of not knowing what was happening. The severity of the migraines threatened to buckle me. I held blocks of ice to my head throughout the day and fell asleep, when I could, with ice packs draped over my forehead. I heard Audre’s words much later when I reflected upon this period in my life: “One of the hardest things to accept is learning to live within uncertainty and neither deny it nor hide behind it. Most of all, to listen to the messages of uncertainty without allowing them to immobilize me, nor keep me from the certainties of those truths in which I believe.” What were those truths? To use all suffering for growth. To speak, even when I was afraid. Perhaps most importantly from that point forward, to practice self-care as an act of political warfare.

Cultivating Fearlessness: Facing Death in Activism

Practices of self-care to heal illness cultivate mental stability and ease. And this peaceful energy, in turn, is extended outward toward our communities as we work to create conditions in which we can thrive.

Audre Lorde named the importance of self-care as she advocated for the rights of Black women in Germany, South Africa, and the United States, and as she advocated for the visibility of gay and lesbian persons worldwide. The work of uplifting marginalized persons was the work of confronting powers that attempt to enact annihilation on the most vulnerable populations in our world. Confronting state violence, even while simultaneously confronting illness and impending death, was lifelong work for Lorde.

This was also true for James Baldwin, who honored the fearless Black civil rights and Black Power activists who looked death in the face—by facing police officers with batons and giving themselves over to arrest. He wrote to Angela Y. Davis during her imprisonment and visibly supported Black Power activists during events and fundraisers. He hailed the civil rights heroes of the South who marched with fortitude against fire hoses and snarling dogs trained on them by city officials. These activists insisted on their humanity and rights despite the virulent hatred of white southerners and hostile northerners. These fearless Black children and parents embodied a capacity to face death and embrace the consequences of challenging the status quo.

Baldwin saw this stamina in the figure of 15-year-old Dorothy Counts, who was one of four Black high schoolers (each enrolled at different schools) determined to fight segregation in their home city of Charlotte, North Carolina. Counts integrated Harding High School by herself, even in the face of threats, physical attacks, and humiliation. This kind of commitment to social justice required a willingness to face death, including the fear of death, Baldwin observed. As a “witness” to the civil rights movement, Baldwin observed that Black people would risk everything, even their lives, to achieve justice for their people. To dismantle oppression and fight for one’s community required facing death for the sake of an expansive, comprehensive freedom.

We enter the movement for social change with whatever we have to offer. For Baldwin and Lorde, the commitment to movement work flowed from their writing. “Freedom is a constant struggle,” Angela Y. Davis wrote. This was true for Baldwin and Lorde. As they faced their own deaths—both from liver cancer—they simultaneously worked on behalf of Black people’s freedom worldwide. They both saw, in collective uprisings, oppressed people’s willingness to face death in their refusal to back down from state violence.

The willingness to face death requires inner fortitude. It requires rest. Baldwin saw this starkly as he observed the grassroots civil rights activists who faced screaming mobs and were terrorized and denied due process simply because they insisted upon respect. He mourned the deaths of his friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., as he attempted to write about their integrity in his unfinished manuscript Remember This House. In pondering his friends’ willingness to face death, he sought to answer a lurking question: What was it about these figures that led them into the fray so that they put their bodies in the line of fire with unfailing commitment? He honored their unfailing stamina.

Facing mortality directly required building emotional muscles and an ability to believe in the interconnectedness of all beings. Audre Lorde wrote of the rising and falling of the nature of life and the relationship between growth and decay. She grappled with the fact of death by attempting to live in the present, giving all of her energies to the necessary work of political and psychological liberation. Lorde saw these different facets of liberation as intertwined: Liberating the mind and heart was inseparable from creating community, inseparable from supporting the liberation of Black South African women from the shackles of apartheid. The work was the same. To focus only on one aspect of liberation was to dismiss how layers of oppression functioned within a complex society. For Baldwin—who died in 1987 at age 63—the capacity to face death was as much an interior, self-reflective process as it was an exterior one. Even as he suffered poor health and was eventually immobilized by illness, Baldwin honored rituals of community and courage: breaking bread at “the welcome table” as well as putting one’s body in the line of fire during a protest, risking arrest and imprisonment, and taking bullets for one’s people.

For Baldwin and Lorde—and the Buddha—facing mortality arose from a direct capacity to see the transient nature of life clearly and to hone in on what mattered most to them. As they turned toward their grief and honored their rage, they simultaneously became less afraid of death. Their fearlessness fueled their capacity to reach outside themselves and attune to the people they loved most and the suffering of those in different parts of the world. Fearlessness fed connection and compassion. Baldwin and Lorde, in reckoning with death, became less attached to their own particular lives and more connected to those whose suffering arose from oppressive conditions. Existence was fleeting; it was also valuable, not to be ignored, dismissed, or denied. Life was to be honored but not attached to, respected but not clung to. Taking into account the fact of impermanence, confronting with passion the fact of death, and practicing self-care in the midst of illness made them freer to offer their lives to others and for others.

♦

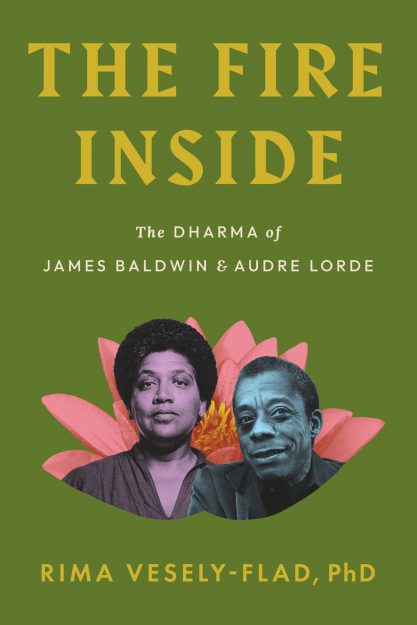

From The Fire Inside: The Dharma of James Baldwin and Audre Lorde by Rima Vesely-Flad, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2026 by Rima Vesely-Flad. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books.

BigThink

BigThink