Taking Stock of Who We Are and What It Means to Be Human

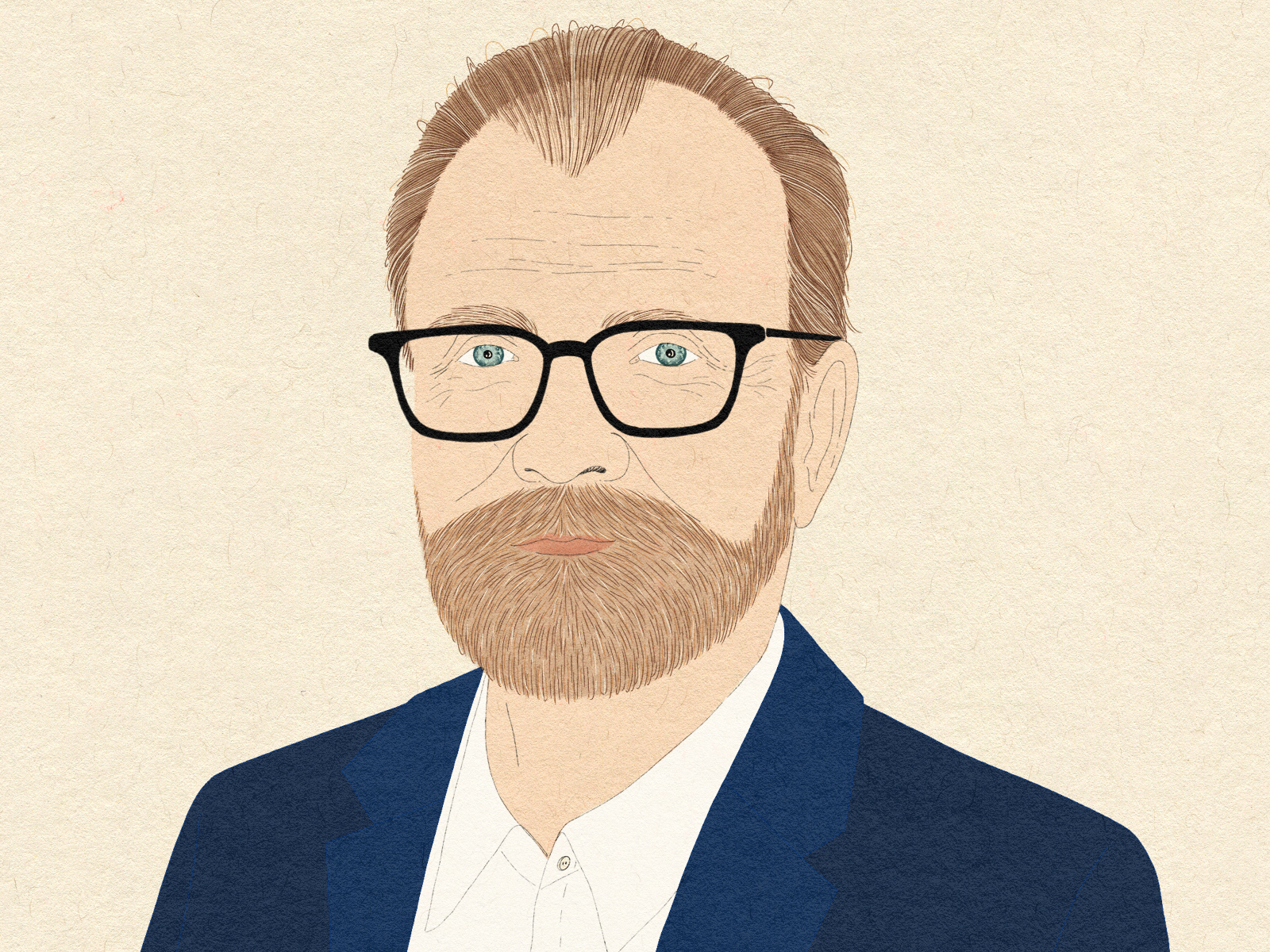

Ann Tashi Slater talks with writer George Saunders about final reckonings, everyday between-states, and being your authentic self. The post Taking Stock of Who We Are and What It Means to Be Human appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist...

Between-States: Conversations About Bardo and Life

In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is a between-state. The passage from death to rebirth is a bardo, as well as the journey from birth to death. The conversations in “Between-States” explore bardo concepts like acceptance, interconnectedness, and impermanence in relation to children and parents, marriage and friendship, and work and creativity, illuminating the possibilities for discovering new ways of seeing and finding lasting happiness as we travel through life.

***

In George Saunders’s new novel, Vigil, an octogenarian oil tycoon and climate-change-denier named K. J. Boone is dying of cancer. “Every day when I was writing Vigil, I was in that death room with Boone,” Saunders says. “And I had to consider, ‘OK, what would he really be thinking?’ ” As he hovers between life and death, Boone is visited by ghosts who lay bare the ethical complexity of how to live in this world and how to leave it, some inclined to forgive him for the environmental destruction he has wrought and others determined to hold him accountable. “Under the duress of your death,” Saunders said, “you might be able to be honest and repent. But nonrepentance is equally possible.” A deeply affecting story, Vigil takes up themes that Saunders also explored in his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo (2017): denial and responsibility, desire and regret, free will and fate.

Saunders was born in 1958 in Amarillo, Texas. In addition to his two novels, he’s the author of story collections including Liberation Day (2022), Tenth of December (2013), and CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1997), and a book about the art of reading and writing fiction, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (2021). His many awards and honors include the Booker Prize, Guggenheim and MacArthur fellowships, and election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He has taught creative writing at Syracuse University for nearly thirty years and is a practicing Tibetan Buddhist.

We talked over Zoom about final reckonings, everyday between-states, and being your authentic self.

*

Where did the inspiration for Vigil come from? From a vague idea that all these people who orchestrated climate denial back in the nineties, mostly men, were getting old. I wondered, with the weather changing so markedly and the consensus on climate change shifting, if people like that would have any misgivings now. Would one of them be able to say, “Oh wow, I was totally wrong.” Or would they continue to say, “No, I did the best I could.” Or, “No, it’s all fake.”

That opened up the bigger question of, “Is any one of us capable of taking stock of who we are and repenting?” Whether your sins are small or large, it’s difficult.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead says that in bardo, we come up for judgment before Yama, Lord of Death. The editor of the first English translation of the book, W. Y. Evans-Wentz, explains that we offer Yama “lame excuses” for our negative actions in life, saying things like, “Owing to such-and-such circumstances I had to do so-and-so.” When I was writing Vigil, I had to think about, “How would I defend myself if I were K. J. Boone?” It held a mirror up to my own mind and how my individual system of denial is constructed. What I discovered was that the category of lame excuses has several anterooms. The first excuses are easily dismissed. Even the person making the excuses goes, “Wait, I have a better one.” Then there’s a second wave of excuses, and a third and a fourth and a fifth, until finally you’re out of lame excuses.

It’s funny because that moment really is just honesty. We all long to be there no matter what type of deceit we’re involved in. It’s such a relief when you finally confess. But if you lock up at the last minute in front of Yama, making a final excuse that isn’t good enough, do you go into the next life in that defensive crouch?

The idea in the bardo teachings is that we cycle back into the same self-justifying existence, into samsaric suffering. Right, right. What I found with Vigil was that some people who’ve lived their lives hardening that system of excuses have a difficult time working their way out of denial. The end of the book was an interesting moment, as I considered: Could a person like K. J. Boone repent?

Vigil continues with the bardo themes you explored in your first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo. Why are you so fascinated with bardo? There’s a high-tone answer, but the low- tone answer, if it’s more honest, is that I’ve always been interested in the possibility of ghosts. I started writing about them in my first story collection, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, because it gives you an extra dimension of time. You’re not only writing about narrative current time, you’re writing about the past as well, and the future.

Also, in a way, writing about ghosts was a reaction against the 1980s New Realism that said the quotidian was all that was real, and therefore the material was all that was real. That’s a beautiful aesthetic, but my life has been full of people I love who have passed away. Letting something supernatural happen in my writing seems more truthful because we always have dead people’s urgings in our head.

Your writing is often about the liminal space between life and death, between the living and the dead. How do you experience betweenness in your day-to-day existence? I experience it in the sense that I feel in between my self-conception, which is very flattering, and my actual, flawed self as I’m walking through the world. Most of my errors, my sins or shortcomings, have to do with anxiety and moving too quickly. I’m impatient, and my mind is super busy. So in the moment, I’m not able to be the best person I can be.

Letting something supernatural happen in my writing seems more truthful because we always have dead people’s urgings in our head.

Writing has a calming effect because I can slow everything down, rewrite fifty times. Long before I knew what meditation was, I was doing something like it in writing. Not because of the ideas that I was writing about but because of the process of saying, “If I’m going to improve these three sentences, I can’t be thinking. I have to just be reading.” Through editing, I’m more patient, more focused and present. It makes me feel like there’s some resolution in that liminal space between my ideal self and my actual self.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead describes radiant, dazzling lights that we see as we go through bardo. They’re the lights of our authentic nature. Do you feel like you are your authentic self? For me, “authentic self” is multiple. I have a lot of selves that come and go. When I’m writing, I can be in a beautiful state of pure concentration. Then, two seconds later, I’m like, “Oh, the New Yorker is going to love this.” Those minds just flip on and off. We can be the person who’s having a thought. We can be the person who’s judging the thought. We can be the person who’s saying, “Don’t judge that thought.” All at the same time.

So I don’t feel that I know who my authentic self is, because in the past, when I thought I did, that person would morph. I once heard somebody say that we present very multiply, depending on the situation. Your true self is just whatever is needed, that’s the part that manifests. That feels truthful to me.

You published your first book in 1996 and have been writing prolifically since then. Sometimes writers feel that writing eclipses living, that it keeps them from engaging fully with the rhythms and pleasures of everyday life. Does the time you spend writing make you feel like you’re not out there in the world? Not really, because I write just a few hours a day. I have a lot of interruptions and responsibilities like teaching, traveling, and taking care of our elderly dog. So I don’t have the problem of feeling that I’m not in life. Maybe more of the other feeling, which is I need to be more disciplined about my writing.

How conscious do you feel that your time is limited? I’ve always had a sense of urgency. Since I was a little kid, I’ve felt like time to get going. And now that I’m getting older and the people ahead of me are starting to go off the cliff, death viscerally seems more real. When I was younger, I thought it went like this: You get older and duller and slower and you can barely move, and then you get sick and you die. But I’ve realized, “No, what also can happen is you’re fine and then you die. And it can happen at any time.”

In the Tibetan funeral ceremonies, lamas guide the dead through bardo by reading from the Tibetan Book of the Dead. One of the things they say is, “You’re dead.” That’s a really hard thing to hear, but at the same time, the lamas are companions along the way, reassuring us that what’s happened is OK, that death comes to us all, and—That’s beautiful. We’re always like, “No, it’s not OK. I’m supposed to play tennis tomorrow.”

Exactly. And like the lamas helping us navigate bardo, your books are companions along the way. They raise hard questions for us to think about, issues at the heart of what it means to be human and, at the same time, reassure us that we’re not alone. Thank you for saying that. I hope that’s true. Vigil certainly has been a companion for me, because to be thinking about those issues, you can’t help but apply them to yourself. The tricky part is K. J. Boone is such an extreme case. He knows what he did, and it’s pretty bad. For me, it’s interesting to go, “I don’t think it’s anything I did, but it’s something about the way I am. Something in my daily being is not quite there yet.” I need to address the shortfall, because if I don’t, I know I’ll regret it.

Do you have any idea of how you’ll address it? Well, I want to do two things: first, write better and go deeper. I want to try to discover a way to accommodate more positive valences in my work without being saccharine. The second thing is I’ve had opportunities to be in different mind-states than I’m in right now, that were more loving, and I know that’s real. I know there’s a path to it. Whether I’m sitting at my desk or waterskiing, if the heart isn’t more loving, then I’m missing that opportunity.

So I’m on alert about this. For me, all paths lead to trying to write better and trying to live better. But then, of course, that second goal has so many side rooms: anxiety, ambition, and the habitual rushing past things that we tend to do. Like, you’re with somebody, you love them. How best do you spend that moment? And it’s not external, it’s internal, right? So I’ve been very lucky to be involved in dharma and to meet people who are on a different wavelength about this stuff. I’m resolved in the remaining years I have left to lean into that more.

ShanonG

ShanonG