Faith Leaders Unite for Call to Action in Minneapolis

A social worker and Zen practitioner reports from the January 23 “ICE Out of Minnesota” general strike and day of action. The post Faith Leaders Unite for Call to Action in Minneapolis appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Some source names have been withheld due to the sensitive nature of this topic.

Minnesotans know how to walk on the ice—how to navigate treacherous, slippery surfaces when every step feels uncertain.

In January 2026, beneath skies the color of steel and in subzero temperatures that turned breath into drifting mist, tens of thousands of Minnesotans gathered not to admire the cold but to confront the chilling reality of federal immigration enforcement (ICE). Across the state, voices called for an end to ICE’s presence in Minnesota and the violence it has brought to our streets, including the fatal shootings of Renée Good and Alex Pretti in recent weeks—deaths that became catalysts for outrage, grief, and widespread mobilization. On January 23, 2026, an extraordinary general strike and protest swelled to an estimated 50,000 or more people, closing schools, workplaces, and downtown corridors in a collective cry: ICE out of Minnesota.

Walking on ice means acknowledging risk. It means moving with attention and intention, knowing that one misstep can lead to a fall. So, too, do we find ourselves in times that demand moral attentiveness and careful, courageous movement. This moment saw faith communities step into the icy wind with resolve. MARCH—Multifaith, Antiracism, Change, and Healing—convened 700 clergy from multiple faith traditions and regions with less than seven days’ notice on January 22, organizing alongside political partners ISAIAH and Faith in Minnesota. Together, they built a coalition of faith-based initiatives responding to ICE’s surge and to growing concerns about the treatment of undocumented people, Black and Brown communities, and citizens alike. As MARCH described it, this gathering was “an initial act of collective responsibility—rooted in relationship, spiritual grounding, and commitment to communities facing heightened harm and scrutiny in this moment.”

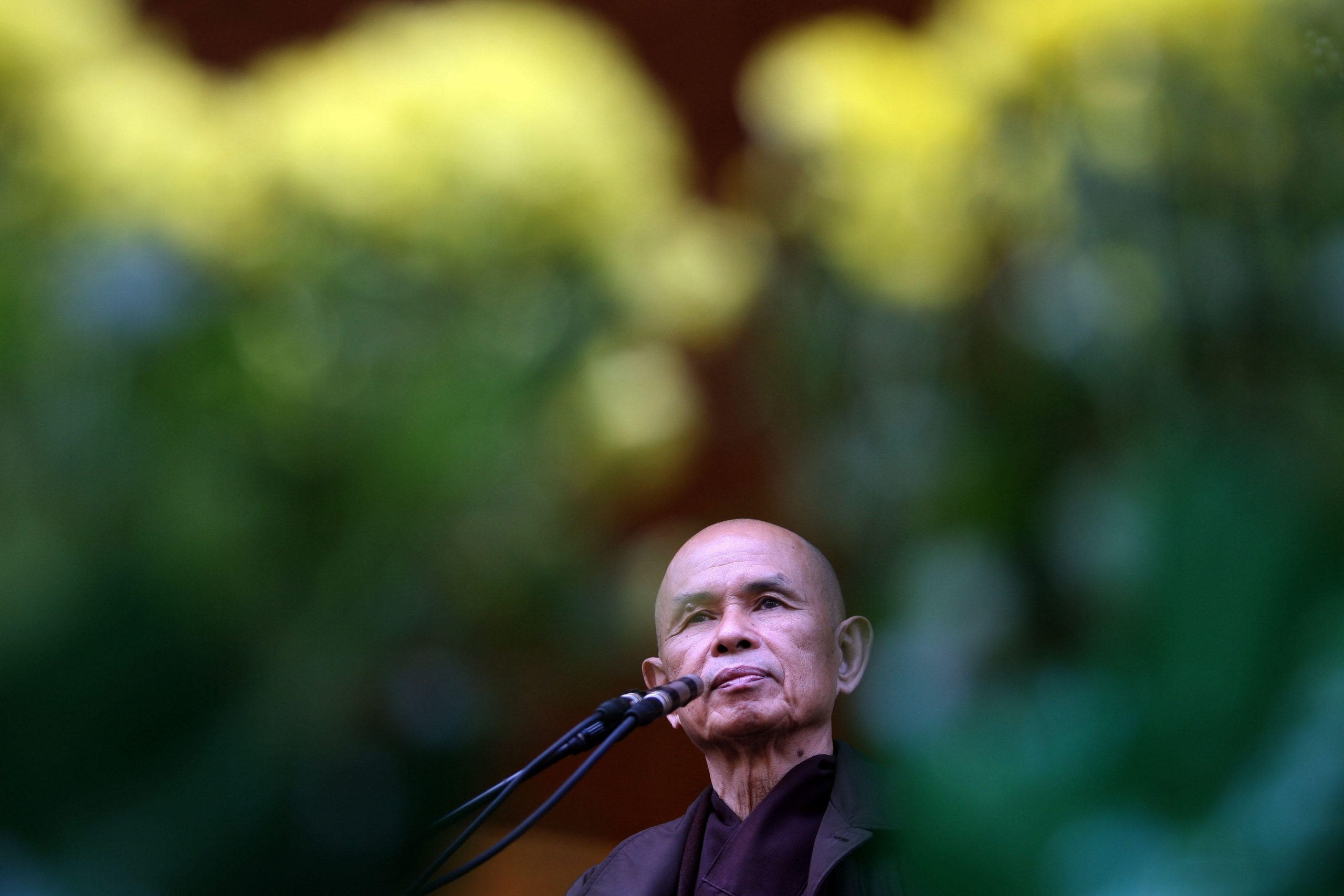

On January 23, those clergy put their faith into action at the Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP), where roughly one hundred faith leaders were arrested during a peaceful protest against ICE’s activities. The clergy led a sit-in at the airport, demanding that airlines stop transporting detainees, part of a wider day of action that saw hundreds of Minnesota businesses closed and thousands participating in demonstrations across the area. Earlier that week, on January 20, Reverend Jinzu Minna Jain of Clouds in Water Zen Center spoke at an ISAIAH press conference, framing the movement as both spiritually grounded and closely aligned with ISAIAH’s long-standing advocacy for community protection and justice.

As a Buddhist priest standing among clergy who joined this movement, Jain understands this moment as one in which spiritual witness and social action converge. Buddhist traditions, they remind us, teach practitioners to face suffering squarely—to bear witness without turning away. In this season, Minnesotans are not merely enduring the cold—they are stepping forward in solidarity, testing each step with compassion and resolve in pursuit of justice and collective well-being.

Another clergy member from Clouds in Water Zen Center who joined the ICE Out of Minnesota protests stepped into this moment with disciplined awareness and deep historical memory. According to this priest, who was arrested alongside ninety-nine other clergy, the action was informed by the legacy of the civil rights movement and figures such as Rosa Parks, whose resistance was strategic, communal, and grounded in conscience rather than impulse. Their reflections reveal how the call to stand with the oppressed is not new but part of a long lineage of collective struggles for justice that are often misremembered or forgotten. Speaking of Rosa Parks, the priest emphasized that “people made conscious decisions about being arrested or not being arrested, and that was intentional, that was an intentionally planned action.” This distinction matters, they explained, because contemporary protest is frequently contrasted with an imagined past that appears accidental, loosely organized, or untrained.

The priest pointed to the ways collective memory distorts the story of Rosa Parks, reducing her to a tired individual who simply sat down. “If we talk about Rosa Parks, people think, oh, she was just a little old lady, she got tired, and she sat down.” What disappears in that telling is the discipline, preparation, and strategy behind her action. “There’s kind of a reason we don’t remember these histories,” the priest reflected. “It isn’t just that we innocently don’t remember them. I think they are, in a lot of ways, condensed and erased so that we think of change as heroic action by individuals, instead of long histories of collective reflection.”

That erasure, they suggested, serves power. It discourages people from recognizing the depth of preparation required for nonviolent resistance—and the moral seriousness of choosing arrest. The airport action, in this sense, echoed earlier freedom struggles. The Clouds in Water priest described coming from “a social justice background” and “a family that has a very strong sense of ‘you must take action.’ ” Yet this moment required a different kind of courage. “I was born thinking that you have to fight,” they said, “but it’s really different saying you have to fight with a gun, and support that, than to say you are now in a position—because of your robes—to stand up for life.”

Photo by Elena Stanton

Photo by Elena Stanton

This reckoning was not only political but also spiritual. Zen practice, the priest explained, could not be separated from the conditions facing their neighbors. “What we do on the cushion is about liberating all beings,” they said. “Beings cannot be liberated if somebody is knocking on their door and dragging their mother out and leaving a 5-year-old with no parents.” In that context, continued meditation without action felt hollow. “If it’s happening in our neighborhoods, I can’t exactly continue to sit on a cushion and be like, well, you know, doing my best for me.”

At the airport, this ethic took the form of disciplined nonviolence. The priest described a moment of shared vulnerability—among both clergy and police—when no one knew how events would unfold. “Nobody knows what’s actually going to happen.” They emphasized that anger and ego would have escalated the situation, increasing the risk of harm. Instead, restraint prevailed. “Nobody threw a water balloon. Nobody threw anything,” they recalled. “In fact, they sang back to the police.” That act of singing transformed the space. “There is so much power when you go into that moment of vulnerability. There is no ego—just faith, precepts, and vow.”

The priest also reflected on the asymmetry of risk. Those most targeted by ICE—Muslim, Latino, Black, and Hmong communities—were not the ones standing at the front. Clergy, largely protected by race and religious vestments, stepped forward intentionally. “The garments we wore also acted like a shield,” they said. As in earlier civil rights struggles, those with relative safety placed their bodies on the line—not as heroes but as witnesses—drawing from a tradition that understands arrest not as failure but as moral testimony.

Reverend Jinzu Minna Jain grounds their reflection in what they describe as one of Buddhism’s most essential commitments: truth-telling—a compassionate, no-nonsense stripping away of delusion. Buddhist practice, in Jain’s framing, is not a refuge from reality but a discipline of seeing clearly, of “witness[ing] and experienc[ing] the bald truth of this small life, within the wide truth of existence.” That clarity, they insist, is urgently required now.

Jain names the truth plainly. “Here in MN, the Department of Homeland Security is engaging in the largest immigration enforcement action in history.” They recount the human cost: people killed, including Renée Nicole Good and Alex Pretti in south Minneapolis, and dozens who have died in ICE custody since the beginning of 2025. They describe the violence as systemic and ordinary—people taken “from home, from work, from gas stations, restaurants, grocery stores, and school bus stops,” as racial profiling, checkpoints, and document checks become normalized. Children miss school. Small businesses close. Deportation flights continue. Even Native Americans, constitutional observers, and protesters are abducted, brutalized, and killed.

Jain widens the lens further, naming the erosion of social safety nets, the rule of law, and constitutional protections, alongside accelerating authoritarianism, environmental devastation, and ongoing genocides—both abroad and at home. “These are violently tumultuous days,” they say, refusing to isolate immigration enforcement from the broader landscape of harm.

“One of the most important things that Buddhists—and interfaith and secular folks—can do in response to this moment is truth-telling: witness and testimony about what is really happening, countering misinformation.”

And yet Jain insists on holding another truth at the same time: “The people of Minnesota are coming together in profound ways to care for one another.” They point to the growth of mutual aid and rapid-response networks, the energy—and even joy—of mass nonviolent mobilization, and the deep debt owed to Black and Brown organizers, past and present, “on whose shoulders the actions of this moment rest.”

When Jain asks, “What does Buddhist practice have to do with any of this?” their answer collapses any imagined distance between contemplation and action. “There is no distance between justice and liberation,” they say. The bodhisattva vow—to liberate all beings—demands engagement with suffering as it is. Racism, xenophobia, transphobia, and fascism are not abstractions but “dharma gates, fires that we must tend.” They add, “One of the most important things that Buddhists—and interfaith and secular folks—can do in response to this moment is truth-telling: witness and testimony about what is really happening, countering misinformation. This is bearing witness, which is something we can do only in community. This is confronting delusion and stripping away ignorance.”

For Jain, practice belongs “within the storm of this moment, not outside it.” Zen offers no escape hatch—only the possibility of becoming “the open and awake eye of the storm,” grounded in compassionate truthfulness and unwavering commitment to collective liberation.

In the end, this winter’s protests have shown once again that when people choose to see clearly, act compassionately, and stand together in the face of violence and uncertainty, moral clarity becomes a path toward liberation. Choosing not to slip into fear or indifference, the collective courage witnessed in Minneapolis signals that this community will keep stepping forward—ever mindful, ever grounded in truth and solidarity.

ShanonG

ShanonG