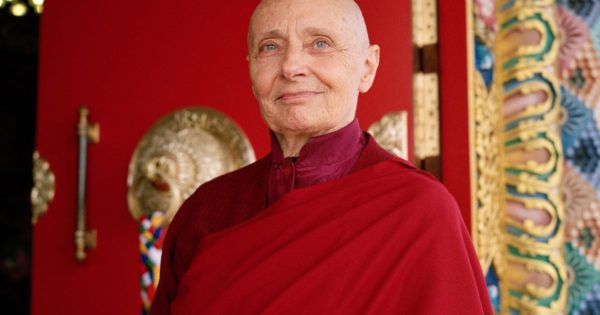

Tenzin Palmo: There Is Nothing a Woman Can’t Accomplish

Dominique Butet and Olivier Adam profile Tibetan nun Tenzin Palmo, who is changing the role of women in Tibetan Buddhist traditions. The post Tenzin Palmo: There Is Nothing a Woman Can’t Accomplish appeared first on Lions Roar.

Dominique Butet and Olivier Adam profile Tenzin Palmo, the nun who is changing the role of women in Tibetan Buddhist traditions. Translated from French by Susan Maneville.

Tenzin Palmo. Photo by Olivier Adam.

A few days after Losar, the Tibetan New Year, spring seemed to be dawning on the Kangra plain, situated in Northern India in the province of Himachal Pradesh. Bougainvillea and magnolias were in full bloom, brightening up the dominating green of the region. The weather was already hot when our taxi dropped in front of the open gates at Dongyu Gatsal Ling, a community of ninety Buddhist nuns founded by Tenzin Palmo nearly fifteen years ago.

Straight away we wondered what pushed Diane Perry, a young English woman who had grown up in London, to leave everything behind for India, shaving off her lovely chestnut curls to become the second Western nun in the history of Tibetan Buddhism. Now known as Tenzin Palmo, she is over 70 and what she has accomplished has become a living source of inspiration.

We arrived at the convent door. She greeted us with a large smile and a firm, generous handshake. She modestly agreed to talk about herself.

Young Diane was born in 1943 and was a solitary child. During adolescence, themes on suffering, aging, and death haunted her. She remembers being thirteen, watching a bus pass in front of her, and observing the people in it talking and laughing. Her reaction was quite surprising: “Don’t they realize, don’t they know what’s going to happen to them?”

“Reading my first book on Buddhism at 18 is what changed my life completely,” she’s said. When she was halfway through it, she announced: “I’m a Buddhist” — to which her mother replied, “Finish the book and we’ll talk about it!” But Diane had found her spiritual path and would follow it with all her strength.

Her meeting with Chögyam Trungpa in London guided her towards Tibetan Buddhism and a search for her own master. In February 1964, she embarked on a cargo boat for a two-week journey that took her to Bombay and then went on to Northern India, where she found a position as an English teacher in a school for young lamas. Just at that time, the headmistress of the school received a letter from the eighth Khamtrul Rinpoche, recently exiled to India from Tibet. “Just reading his name,” Palmo recalls, “I knew that he would be my master.”

When he arrived at the school a few weeks later, she hurried to greet him, without daring to look at him directly. She whispered to her headmistress: “Just tell him I want to take refuge with him.” “Of course,” he answered. “I knew immediately,” she says, “that he was my master. And he knew immediately that I was his disciple.” The eighth Khamtrul ordained young Diane as a nun and gave her the name Tenzin Palmo.

She went with him to the Tashi Jong monastery in Himachal Pradesh, where she discovered the existence of the Togden, “beings who have realized the nature of the mind and are able to control it, after a retreat of more than fifteen years.” With their hair in dreadlocks and wearing the white robe inherited from Milarepa, these yogis were said to have unusual spiritual capacities. The young nun learned that while in Tibet, her guru lived among the Togdenma (the female Togden), though they did not survive the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

“I then told my master that I wanted to become a Togdenma. He was so happy. He said he’d been praying I would re-establish this order. However, when the monks heard about the project, they declared, ‘a woman is not going to live with the Togden.’ And so, I had to renounce.” She was the only nun in the middle of about a hundred monks. “I made the vow to be reborn in the feminine form until I attained enlightenment.”

Tenzin Palmo was only twenty-six when the Khamtrul encouraged her to go on a retreat and sent her to Lahaul, near Keylong. “This retreat was a vocation for me, it was what I was called to do in life,” she recalls. The cave she chose for her purpose was situated at an altitude of 4300 meters, difficult to access. She would spend twelve years there.

One winter, after seven days of continuous driving blizzards, Tenzin Palmo discovered that the height of snow had covered the openings of her cave and that she was imprisoned. At first she got herself ready to be buried alive, but then she heard an inner voice telling her, “Dig!” She immediately seized her saucepan lids and started digging. After long, terrifying minutes, she finally reached outside air. However, when she went back into her cave, she “realized that the ambient air was not contaminated but fresh. This was how I discovered that caves and snow breathe and that I wasn’t going to die.”

“Another advantage of the cave,” she says, is that it always gives you the space necessary for perfect concentration. And for me this was a source of great joy. I wouldn’t have wanted to be anywhere else.” Did she have any difficulties? “Of course, certain days were marvelous and there were others of extreme unease when I wished I could do something other than sitting and meditating! But, these highs and lows are natural. Whether it rains or the sun shines is not important. The weather passes and we continue meditating.” Was it more difficult for a woman to live as a hermit in the mountains? “Not at all,” she replies.

Next we asked Tenzin Palmo about the actions she’s led in favor of women. Her enthusiasm was unmissable.

The Dongyu Gatsal Ling project began some time after the end of her retreat. Tenzin Palmo had responded to an old request of her guru: “to found a community for young girls from Himalayan regions [e.g., Ladakh, Bhutan, Spiti, Nepal] who want to become nuns and study according to the traditions of the Drukpa Kagyu.” As her work to reintroduce the Togdenma lineage was beginning to take shape, she praised the commitment of “the nuns who not only seriously study Tibetan Buddhist philosophy, and the founding texts of the tradition, but also practice the rituals with a lot of dedication. At the end of their study program, they can decide to go on a long retreat.”

“Throughout Tibetan history,” she notes, “there have been many great female meditators—yoginis—but little has been written about them, so they are not very well known.” But the tide is turning. “After having been completely neglected, ignored, and underestimated by Tibetan society, the nuns are now starting to become more popular. People are at last aware they exist and are bringing them real support. And there will soon be geshema! [The geshe degree is the monastic equivalent of a Ph.D in Tibetan Buddhist studies, and until recently has granted to men only.] From now on, there is nothing you cannot accomplish in a woman’s body.”

After a pause, her brow immediately darkens. “The ones that haven’t [benefited] are the non-Himalayan nuns. Not just the Western nuns but also those from places such as Taiwan or Vietnam and so on that have joined the Tibetan movement. They receive no financial or moral support from anyone. In most cases, they dedicate themselves to running the Western Buddhist centers and have to pay rent and electricity, without any income. This is why I’ve undertaken the creation of an Alliance of Non-Himalayan Nuns, so they can stay in contact and are no longer isolated. But the first thing to do is to spread the message that they exist so that people become aware. It was the same when I started talking about the Himalayan nuns twenty years ago. First people said “Oh! Are there nuns? I never realized…” And then, they asked: “What can I do to help them?” That was when I was able to raise money to build this nunnery. Now the time has come to look after the non-Himalayan nuns.”

Indeed, in June 2015, she took part in the Sakyadhita Conference, an international gathering of female Buddhists created in 1987 of which she has been chairperson since 2013. Her presentation there concerned the non-Himalayan nuns.

In 2008, when the Gyalwang Drukpa suggested awarding her the title Jetsunma in recognition of her spiritual growth and her work with women, Tenzin Palmo’s first reaction was to refuse such a distinction. “But,” she says, “I received so many e-mails saying how wonderful it was and how it highlighted the status of women that I realized this title had nothing to do with me but concerned women in general. And for this, I could only say thank you.” So she took advantage of talking with Gyalwang Drukpa about the names usually given to the nuns, like Ani (aunt) or Chomo (woman of the house). She then suggested “Tsunma”—a reference to something noble, delicate, pure. The nuns approved the idea and started using this term with each other. “When the Karmapa came to visit Dongyu Gatsal Ling in 2014, I noticed that he also used this term. That was wonderful. The sound of the word immediately gives a positive impression in the Tibetan mind and you know how much we are influenced by language.”

Troov

Troov

.png?trim=0,0,0,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)