The Backwards Wisdom of Shikantaza

Radical acceptance of what is changes how we experience life. The post The Backwards Wisdom of Shikantaza appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Photo by Nancy Nguyen

Photo by Nancy NguyenThe root of human suffering (dukkha) is found in our countless desires to change life’s circumstances to satisfy those desires. Many of those desires are extreme or unending. They are the source of disappointment and anger, as well as the trigger for other harmful emotions such as jealousy and anxiety. Thus, we might think that we must achieve all those goals and desires to be happy, removing one by one the endless targets of our anger, sadness, and fear in order to feel satisfied. We think we need to work to fix these things.

However, the surprising twist of shikantaza, or “just sitting,” is that one sits feeling radically satisfied just by the act of sitting, putting down all measures of some “lack” and desiring nothing but sitting. The root of disappointment, anger, comparisons, despair, fear, frustration, and other desires drops away, and thus dukkha drops away. The goal of sitting is sitting, which is satisfied by sitting.

As counter-intuitive as it sounds, there is simply nothing more to desire, nothing else to change or fix, during the time of sitting, and that fact changes—and actually fixes—a lot about what ails us, because the anger, fear, and all the rest lose their fuel. Anger and fear evaporate through radical acceptance of what is, and through our not demanding or wishing anything else but sitting while sitting. Acceptance thus changes how we are and how we experience life, nullifying anger and fear.

Another counter-intuitive fact about shikantaza is that—neither while sitting, nor at other times—do we care about kensho, an experience of the hard borders of self and the world dropping away, and all phenomena flowing in and becoming one with us and all. Nor do we hope for pleasant samadhi, concentrative states while sitting. We do not seek anything in the whole wide world while sitting. We take sitting, as a matter of profound trust, to be itself the action and embodiment of Buddhas and ancestors. We sit needing nothing, neither kensho nor no kensho, neither samadhi nor no samadhi, for all we need for completion is to sit… and we are sitting.

Anger and fear evaporate through radical acceptance of what is, and through our not demanding or wishing anything else but sitting while sitting.

Funnily enough, though, by the very action of sitting just to sit, with its accompanying equanimity and leaving aside other desires, and whether we’re following the breath or sitting in open awareness, the hard borders between self and the rest of the world may indeed soften, sometimes fully dropping away, with all phenomena flowing in and out to become each other and all reality. For some folks, it is a sudden and profound experience that may last a short or long time. For others, it is a more subtle wisdom that gets into the bones over time. He who walks through the mist slowly, and she who dives into the ocean deeply, both become just as wet. In fact, both prove to be the very ocean flowing all along. A sudden and steep kensho or a slow and subtle kensho is all still kensho, still the very same wisdom.

Likewise, shikantaza is always perfect, whether samadhi is reached or not. But another funny thing is that our sitting with trust in sitting’s perfection, nothing else sought, simply following the breath or openly aware, can bring about rich experiences of samadhi. It is like a present that one receives when one stops wanting or trying to get it. Samadhi can just happen. And if it doesn’t, zazen is still perfect.

Sometimes we can’t sit zazen. If, because of severe pain, life trauma, or other truly unavoidable reasons, we cannot sit, even for a minute or two, then we accept that, too. No need to sit zazen. But when we can, it is lovely to just sit zazen with the pain, trauma, or whatever life shoves one’s way, letting the pain, trauma, or life just be, with no demands on them. We let the pain just be the pain on one mental channel, even as another part of us dislikes it and hopes for a cure.

This is how the very act of sitting without aiming to change, without aiming to attain anything, attains something most profound that truly changes us and all our encounters with the world. It is a most profound dropping of the demands, frictions, and separations of body and mind—sometimes deep, sometimes light, sometimes not at all. (Yet, we know, as a matter of faith, the moon is always shining even when it’s hidden behind the clouds).

Then, rising from the cushion, returning to this world of problems to solve, things to fear, and places to go, with many things to change, and many things lacking, we set to work. But now, we have the knowledge deep in our bones that there is actually nothing to change or fear, nothing lacking, and nowhere else to go.

Get Daily Dharma in your email

Start your day with a fresh perspective

Explore timeless teachings through modern methods.

With Stephen Batchelor, Sharon Salzberg, Andrew Olendzki, and more

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

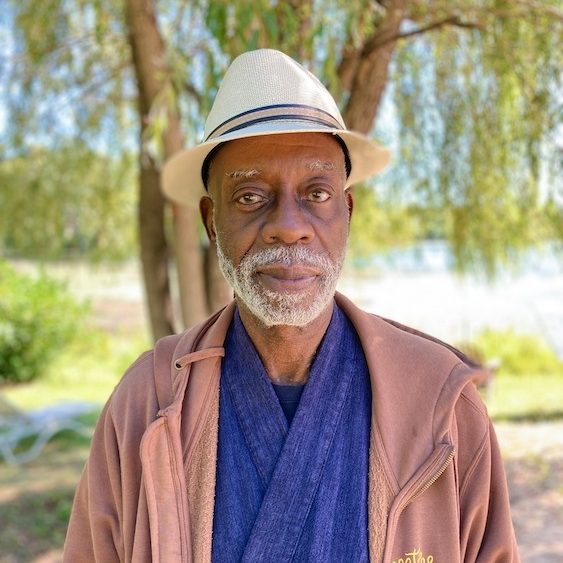

JaneWalter

JaneWalter