The Bardo of Dementia

Ocean Vuong’s new novel follows the unlikely friendship between a young writer on the edge of suicide and an elderly widow reckoning with the loss of her memory. The post The Bardo of Dementia appeared first on Tricycle: The...

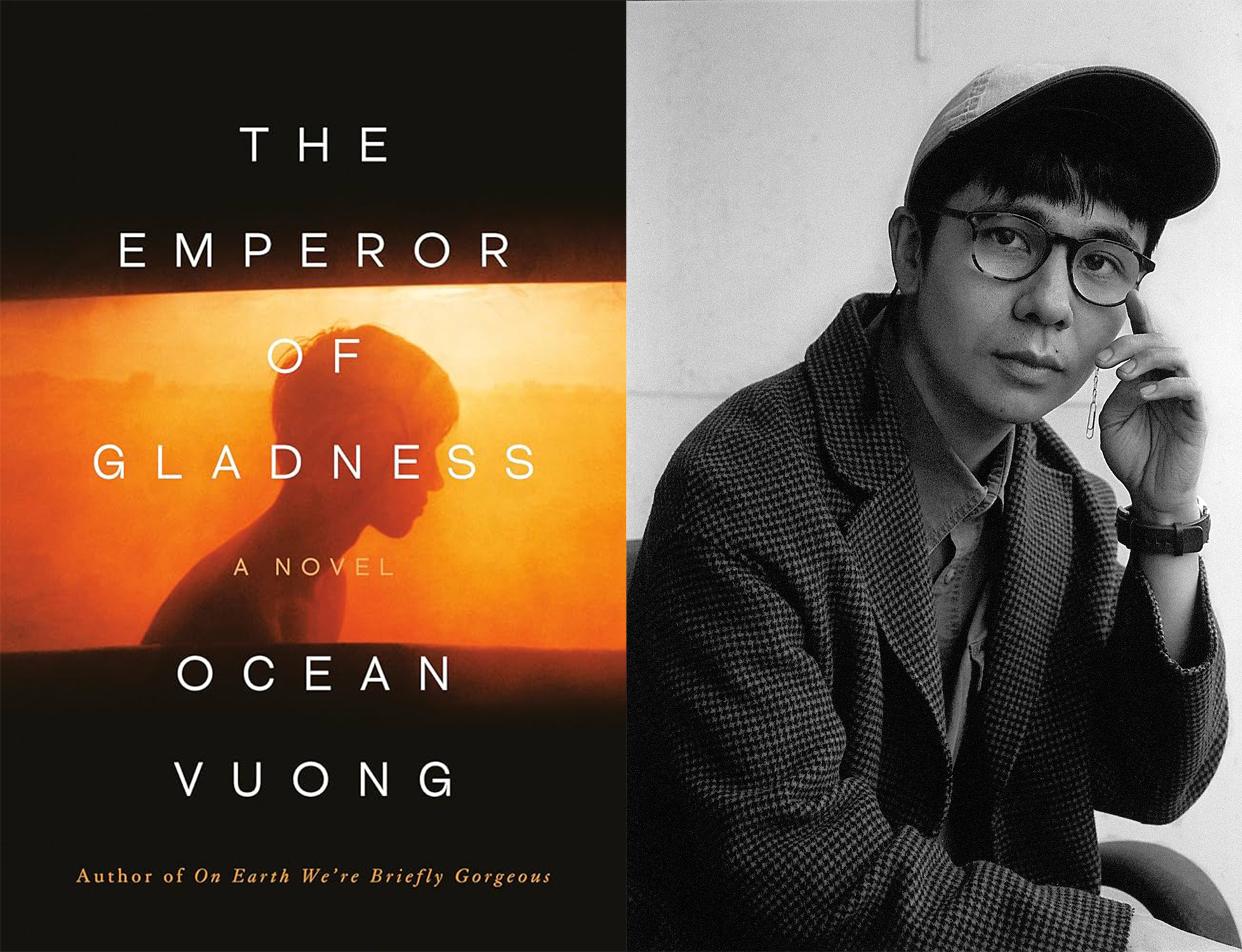

For poet Ocean Vuong, the act of writing is inextricably linked to his Zen Buddhist practice. In a previous episode of Life As It Is, he told Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, and meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg that he believes the task of the writer is “to look long and hard at the most difficult part of the human condition—of samsara—and to make something out of it so that it can be shared and understood.”

Now, in his new novel, The Emperor of Gladness, Vuong turns his attention to our cultural avoidance of illness and death, as well as the small moments of care and kindness that are essential to survival. Tracing the unlikely friendship between a young writer and an elderly widow who’s succumbing to dementia, the novel reckons with themes of history and memory, loneliness and heartbreak, and failure and redemption.

In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, sat down with Vuong to discuss how he incorporates Buddhist notions of emptiness and nothingness into his writing, the role of ghosts and the dead in his work, how writing can be a form of prayer, and what he’s learned from Buddhist understandings of redemption.

To start, can you tell us a bit about the book and what inspired you to write it? I’m always thinking about death, perhaps in the Buddhist sense. My whole life has been informed by intergenerational relationships, and I’ve noticed that in our culture, the very young and the very old are kind of pushed toward the fringes of society. They’re no longer in the center. The young are deemed to not have enough experience to contribute, and the old are deemed defunct. And I think the relationship between that, the foundation between that, is an immense loneliness between those two poles of our society. To me, the tension and the common ground between those spaces is fertile soil to write about not only human life but human troubles: What good is hope when there’s no point of it, when it doesn’t drastically change your life? I don’t have any answer, per se, but I’ve always been haunted by those questions.

The book begins with a haunting description of the town of East Gladness, Connecticut. Could you speak to the juxtaposition of abundance and decay you describe and why you chose to open the book that way? I’ve always wanted to start a book in a way that only a novel can do. And so I have this long, seven-page opening that becomes a painstakingly detailed portrait of this town, describing its history, the decay, and the life shooting through the decay. I wanted to just sink into a time-lapse description, because I think description is autobiographical. There’s so much revealed in who we are by how we describe things. What does it say about a person that they describe stars as exit wounds?

This also goes back to Zen. Whitman famously asked, “What is the grass?” And in Zen, we have to kind of undo grass. We have to forget grass to see more of it. We have to forget the terminologies. And so I wanted to sink into the descriptions but also forget story or suspend story for a while. We always think the novel should tell the story. But the word narrative comes from the Latin root narus, which means knowledge. So to narrate is also to give knowledge, and static description is just as propulsive to me as plot. And so that was the aspiration, and I hope readers will be drawn into this little town.

Well, the descriptions are fantastic, and the world you describe is a haunted one, with the ghosts of history and memory lurking throughout. Could you say more about the role of ghosts and the dead in your work? Well, I think history is haunted. One of my favorite theorists, Mark Fisher, borrows from Derrida, and he talks about hauntology. He proposes that everything we touch in the material present has a history. You know, you drink a bottle of water. Where are the plastics made? What is the runoff? Does it run into a river, which is then harvested and poured again into the bottle? Whose river is it? Who lived there? Who was killed to possess it? Who is it poisoning? Who is it denying? Who doesn’t get access to it? I mean, that’s one bottle of water. And of course, if we live like this, our heads will probably implode on a daily basis. But a novel offers an alternative way to see time, and so the novelist gets to control where we focus, where we zoom in and out. To me, the hardest thing to zoom in on in a novel is history, and yet, when you do so, it keeps giving. I think there’s never a place that is unexamined that doesn’t have a haunted portion of it.

There’s so much revealed in who we are by how we describe things. What does it say about a person that they describe stars as exit wounds?

Fisher also talks about the eerie and the weird, and he says something really unique, where he says the eerie is presence that fails to manifest. He talks about ruins behaving this way, or forests without leaves. So there’s this gesture toward capacity, toward presence, that fails to manifest. And then I thought, well, isn’t that sunyata? Isn’t that nothingness? Is nothingness eerie? I don’t know yet, but it’s a new thought. I think, for me, the eerie is very potent. I’m always drawn to it. I don’t turn away from it at all. When you see ruins, you want to walk up and touch it and run your hand through it, right? That’s presence that fails to manifest. In the heart of eeriness and discomfort is a kind of ultimate generative possibility in the Buddhist sense. I haven’t worked that out yet completely, but there’s something there. I’m just trying to lean into that.

In this book, the characters are haunted by war—Hai’s family by the Vietnam War; Grazina by the atrocities of the Second World War. At a certain point these wars start to all blur together, and Hai responds to Grazina’s fading memory by going back into the past with her and creating new narratives of survival. So can you say more about how these characters find meaning in the parallels between different stories of struggle? What Hai realizes is that dementia is its own world, and the reality is that people with dementia can’t choose which world they’re in. Having friends and relatives who lived through that, I’ve seen it firsthand, that they are literally thrown. They are ejected from the present into an elsewhere. And sometimes it’s not the past; it’s truly an elsewhere, which is then reminiscent of the bardo, or this idea that when the consciousness is out of body, the body is no longer stuck in time and space, and it becomes this kind of hyper-hallucinatory, pyrotechnic, kaleidoscopic horror, in a way.

What I’ve noticed with folks in dementia is that they’re actually heading there sooner than us. The body, with the physical neurons and the holes in the brain with frontal lobe dementia, is creating a kind of other consciousness. I wanted to have a character meet the person there, because if someone can’t choose where their memory is, then you have to go there with them. That then becomes a meditation on fiction, on storytelling: What is real? What is unreal? What is a hallucination? And then you arrive again at a very Buddhist center, which is a Buddhist phenomenology: What is the real, and is it all just a projection of the self? The particular is the universal manifested through perception. I think at the end of it, everything comes back to my understanding of Buddhism.

This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

An excerpt from The Emperor of Gladness:

“Come in. But take off your shoes. My husband put down these floors.” The woman disappeared into the house. The boy hesitated, looking down the empty street. The rain was picking up again. He stepped onto the porch, water running off him in rivulets, took off his boots, and followed her inside.

A creaky rail house built by freight workers over a century ago, the home was one large hallway divided into three rooms: a parlor, a dining room, and a kitchen, whose dim light now glowed at the far end like the hearth of an ancient cave. Furnished in a style the boy had seen only in the black-and-white TV series Lassie, whose reruns he watched on a three-channel Panasonic as a kid, the house had the stuffy odor of rooms whose windows rarely opened undercut with the mildewy rank of crawl spaces. As his eyes adjusted, amorphous furniture upholstered in sprawling pale florals came to view. The walls were wood-paneled and adorned with cheap landscape paintings in gilded frames. As he passed the transom that divided the parlor from the dining room, he looked up and saw what was once a white cross, now phantom-grey from decades of dust. On one wall, lit by streetlights, a cluster of grim-faced portraits stared out from an era he couldn’t locate. He paused at the kitchen’s threshold, water falling from his chin and hair on the laminate floor.

The woman sat down at a small table and nodded toward an empty chair. “Go on, sit. You look like a dunked cookie.”

He sat carefully, his eyes taking in the room. Not knowing what to do with his hands, the boy placed them, palms up, on the table but withdrew them to his lap when he realized this looked psychotic.

“Here, dry yourself.” She handed him a dish towel. It smelled of raw onions but he wiped his face anyway, his eyes quickly stinging.

“Poor kid,” she mumbled to herself. “Hey, it’s all over now, okay? Whatever happened is over. But don’t you cry, boy. Tears deplete your iron, you know.” She grabbed the rag, leaned over and dabbed his eyes some more, deepening the burn. He winced and turned away. “Okay, you’re not a boy. You’re a man and don’t need nobody to wipe your tears.”

The kitchen was the size of a large shed and contained a stovetop browned with grime-stuck grease, a sink, and a portion of countertop the size of a cutting board. They sat at a round table covered in plaid plastic meant to look like picnic cloth. From its center, a fabric-shaded lamp trimmed with tulle emitted a sickly amber glow.

She grabbed a nearby pack of cigarettes, a brand he didn’t recognize, slipped one between her lips, and put a lighter to it. “I normally don’t smoke.” She took a drag and stared at him, not unkindly, then leaned over and pushed aside a large stack of magazines. They were decades old and printed in a language he couldn’t make out.

“Lithuanian,” she said, clocking his curiosity. “Know what that is?”

He shook his head, wiping the onion tears from his cheeks.

“An old country, far away, where I was born.” She waved the cigarette about and took a drag. “But all countries are old, if you think about it.”

But he had never thought about it. He had rarely thought about any country, least of all the one he was born in—only that it, too, was far away.

“Want one?” She handed him a cigarette.

Before he could answer she placed it in his mouth and lit it.

“You like my owls?” She pointed over her shoulder where an armoire loomed behind her. Behind its glass doors was a fleet of owl figurines of many shapes and sizes, some porcelain and shining, others the matte of wood or clay. “Every owl was made in a free country. None of my owls,” she leaned back, “came from Communists. Understand?”

He lied by nodding.

Above the armoire were three paintings of owl portraits, their faces bloated as old mobsters, each one depicting, like a Rembrandt study, a new angle to the bird’s face. In fact, owl knickknacks, tchotchkes, and icons stared at him from nearly every surface. “I collect them. Don’t know why really,” she shrugged. “People started giving them to me long ago. Now it’s my calling card.” She smiled weakly through the smoke. “What’s your name anyway?”

“Thanks for this.” The boy took a long drag from the bogie. “But I should go.”

“Easy, little lamb. I invite you in my home, give you cigarette. And look,” she tilted the pack to show him, “I only have two left. I even let you cry in my kitchen. You know it’s bad luck to cry in the kitchen, right? You can at least tell me your name.”

He stared at the plastic coverlet on the table pocked with holes and considered the name his mother gave him, the thought of it sinking him. It wasn’t that he didn’t like his name—only that he had been willing to toss it in the river. He had never wanted to throw his name out, just the breath attached to it. The name, after all, was the only thing his mother gave him that he was able to keep without destroying.

“Hai,” he mumbled.

“And hello to you too. But—”

“No, Hai. It’s—”

“Okay,” she breathed, “but who am I saying hello to?”

“My name is Hai.”

“Your name is Hello?”

He decided to nod. “Sure.”

“Ah.” She brightened and pointed a crooked finger at him. “So your name is Labas!”

“What?”

“Labas means ‘hello’ in my country.” She extended her hand across the table for him to shake. “Hello, Labas. I’m Grazina. Means ‘beautiful.’” She grinned, the cigarette smoldering through her yellow teeth.

He shook her hand, cracked dry and warm. “Hello.”

♦

From The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Ocean Vuong.

FrankLin

FrankLin