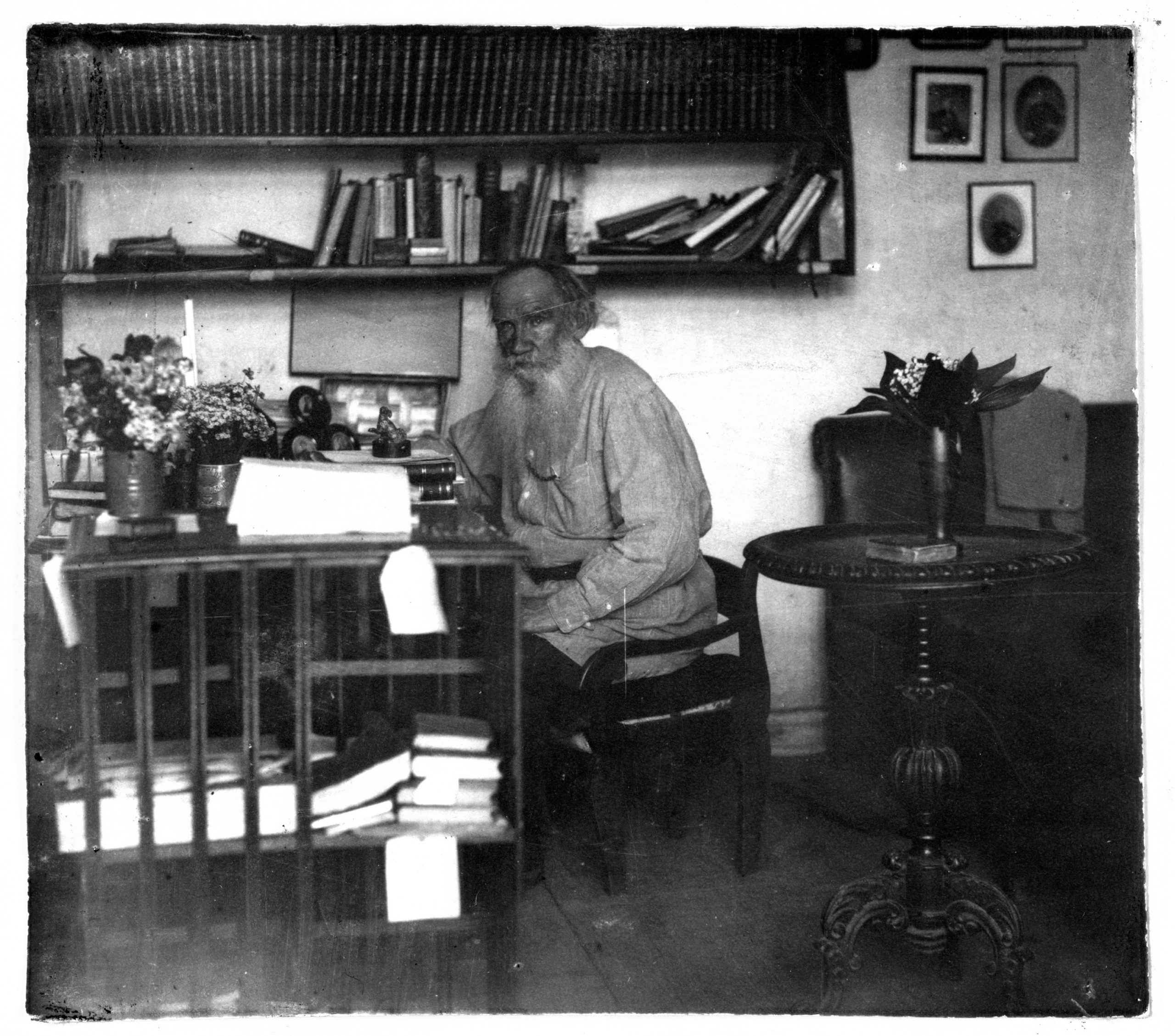

The Buddha of Yasnaya Polyana

Looking back at the Buddhist leanings and spiritual scavenging of Leo Tolstoy The post The Buddha of Yasnaya Polyana appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

In 1847, during the final year of his studies at Kazan University, Leo Tolstoy checked into a hospital to receive treatment for venereal disease. While there, the future author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina shared a room with a Buddhist lama who had been attacked by bandits while traveling across Siberia. As the story goes, the lama told Tolstoy that, instead of fighting back, he merely crossed his arms over his chest and “prayed to Buddha to forgive the lawbreakers.” Some say it was through this chance interaction that Tolstoy, already disillusioned with formal education and ready to return to his family home at Yasnaya Polyana without a degree, first learned about nonresistance to evil—a principle he would preach, both in life and in writing, until his death in 1910.

In his famous essay The Hedgehog and the Fox, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin describes Tolstoy as an intellectual and religious scavenger, someone who constantly jumped from one school of thought to another in search of answers to life’s greatest questions. As is the fate of many such scavengers, scholars have long disagreed on which of these schools ended up having the strongest impact on his development as a writer and thinker. Some see Tolstoy as a quintessentially Christian figure, shaped by both his upbringing in the Russian Orthodox Church and his advocacy for small sects like the Doukhobors and the Molokans. Others insist his worldview was rooted not in religion but in political and economic theory, the result of his infatuation with the likes of Robert Owen, Henry George, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

A third strand of commentary posits that Tolstoy was more drawn to the East than he was to the West, and that many of his most cherished values—including nonresistance and worldly asceticism—originated from his exposure to Hinduism, Daoism, and Buddhism. This position, like all positions on Tolstoy, has its drawbacks. While the author was indeed familiar with and drew inspiration from a variety of Buddhist texts, the influence these had on his oeuvre has been repeatedly overstated and misunderstood—a trend partly attributable to the fact that, for a long time, those who wrote on the subject were either experts on Tolstoy but not Buddhism, or on Buddhism but not Tolstoy.

Fortunately, pioneering research from people trained in both disciplines—notably the late Dragan Milivojevic, Professor Emeritus of Modern Languages at the University of Oklahoma—has cleared up much of this confusion. Yes, Tolstoy was, to a degree, influenced by Buddhism, but his understanding of Buddhism was severely limited by the quality of the studies and translations that were available to him. He was also swayed by personal beliefs and experiences. Determined to discover and synthesize what he believed to be the underlying truths that united all the world’s religions and moral philosophies, he was interested in Buddhism only insofar as it provided him with usable building material for the construction of his own Tolstoyan church.

When and why Tolstoy began studying Buddhism in earnest is unclear. Some point to the prolonged crisis of faith he faced in middle age, when growing frustration at Orthodox Christianity’s dogmatic rituals and secular ambitions compelled him to seek solace in the wisdom of other world religions. Others argue that his interest in Buddhism was, first and foremost, a by-product of his interest in the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, whose seminal text, The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy picked up after finishing War and Peace. While Schopenhauer himself did not become acquainted with Buddhism until after finishing The Word as Will, which posits that the essence of existence is striving, and striving begets suffering, he was amazed at how many of his own ideas resembled those found in the Buddhist canon.

Except for his supposed tête-à-tête with the wounded lama, Tolstoy—like Schopenhauer—mostly encountered Buddhism through the work of early Western enthusiasts. His close friend, the philosopher Nikolay Strakhov, recommended a variety of English, French, and German texts hot off the press, including Eugène Burnouf’s posthumously published translation of the Lotus Sutra, Le Lotus de la Bonne Loi, and Die Religion Des Buddha und ihre Entstehung, a survey of Buddhism’s origins by the German historian Karl Friedrich Koeppen. Tolstoy also met with Russian scholars, befriending Ivan Minaev, a professor of comparative philology at Saint Petersburg and one of the city’s first resident Buddhologists, and Helena Blavatsky, a founding figure of the New Age movement.

Considering the Western interest in this field was still in its infancy, it should come as no surprise that most of the research from this period has since become outdated. As Milivojevic observes in his essay “Tolstoy’s Views on Buddhism,” the “prevailing of opinion of European Buddhist scholars in the 19th century [was] that Buddhism is a life-denying, nihilistic religion” according to which existence was inherently and irrevocably evil, and escape from suffering was achieved only in death. Not unlike how Romantic literature and poetry perceived a sublime beauty in suicide, nirvana—far from being understood as a state of liberation or bliss—was seen as synonymous with nonbeing. “The Buddhist,” wrote the French philosopher Jules Barthelemy Saint-Hilaire in his 1860 text The Buddha and his Religion, “does not look for absorption, but only absolute annihilation.”

Tolstoy not only accepted this pessimistic take on Buddhism but also incorporated it into his writing. “Where did I leave off?” Anna Karenina asks before throwing herself in front of a train, an act Tolstoy compares to blowing out a candle. “On the thought that I couldn’t conceive a position in which life would not be misery, that we are all created to be miserable, and that we all know it, and all invent means of deceiving each other, and when one sees the truth, what is one to do?” A similar sentiment can be found in The Kreutzer Sonata. “But why live?” asks its protagonist, Pozdnyshev, who—like Anna—becomes stuck in an unhappy relationship that ends up driving him to violence. “If life has no aim, if life is given us for life’s sake, there is no reason for living. And if it is so, then the Schopenhauers, the Hartmanns, and the Buddhists as well, are quite right.”

Tolstoy’s understanding of Buddhism is outlined more clearly still in his nonfiction. In A Confession, an essay about his struggles with melancholia, the author explains his situation by way of a famous Zen parable about a man who, running from a tiger, ends up dangling from a vine above a dried-up well with a dragon waiting at the bottom. Unable to escape, he savors bits of fruit and honey as two mice—one black, the other white—gnaw at his lifeline. “The delusion of the joys of life that had formerly stifled my fear of the dragon no longer deceived me,” he writes. “No matter how many times I am told: you cannot understand the meaning of life, do not think about it but live, I cannot do so because I have already done it for too long. Now I cannot help seeing day and night chasing me and leading me to my death. This is all I can see because it is the only truth. All the rest is a lie.”

In the same text, Tolstoy calls on Solomon, Schopenhauer, and other “great sages” for spiritual guidance. He also consults Siddhartha Gautama, whose life story he distills into the following lesson: “It is not possible to live, knowing that suffering, decrepitness, old age, and death are inevitable; we must free ourselves from life and from all possibility of life.” There are many ways to look at this quote, but Milivojevic boils it down to this: Tolstoy, “overawed by the enormity of its consequences,” accepts the first of Buddhism’s four noble truths—that life involves suffering—without ever considering the other three. This blind spot, born from and further contributing to his despair, says as much about Tolstoy as it does about his reading material. Had the author been exposed to studies and translations that did not present Buddhism as some kind of ascetic death cult, his confession might have ended on a more hopeful note.

Tolstoy, “overawed by the enormity of its consequences,” accepts the first of Buddhism’s four noble truths—that life involves suffering—without ever considering the other three.

Tolstoy’s interaction with Buddhist sources was also mediated by his own spiritual development. Though raised Christian, Tolstoy—by his own admission—had never been a model believer. As a child, he wrote, he’d followed the rules of the Orthodox Church the way children followed every other rule imposed upon them by the adult world: mechanically and without thought. When, after giving in to hedonism as a student and army officer, family life beckoned him back onto the religious path as an educated, inquisitive adult, he struggled to find his footing. No longer willing or able to take the workings of the Church at face value, he failed to see the justification for its esoteric rites and rituals, much less the wealth and power of its extensive bureaucracy. These things, it seemed to him, ran counter to all that Christ had said and stood for.

As exemplified by the title of his 1894 treatise The Kingdom of God Is Within You, Tolstoy eventually came to believe that organized religions were self-serving shams that exploited the legacies of their visionary founders. Just as he accused the Church of obstructing the practical, rational contents of the gospel behind miracles and mysticism, so, too, did he judge contemporary Buddhism as a corrupted version of what the Buddha had originally intended. “How it was perverted,” Tolstoy said to his secretary in 1908 after reading about the complex cosmology of Mahayana Buddhism. “Suddenly there appeared the same creation of gods, the idol worship, the paradise and the hell . . . quite the same superstitions as in Christianity.”

Tolstoy’s excommunication from the Orthodox Church in 1901—resulting in large part from criticisms he had conveyed in The Kingdom of God Is Within You—only fueled his skepticism. As Marina Alexandrova, a teaching fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, writes in an article titled “From Christ to Krishna: Tolstoy and Eastern Philosophies,” the author became convinced that “all major religions differ only on the surface, while the ethical foundation is identical.” In writing and conversation, Tolstoy insisted he had arrived at this foundation by comparing and contrasting the canonical texts of various faiths. In truth, the author’s notion of what constituted “foundational” had been formed a priori, informed heavily by his clashes with the Church. At the cost of undermining Berlin’s iconic categorization, one could argue Tolstoy didn’t immerse himself in Eastern thought to forage for fresh ideas but to find confirmation for what he had already believed.

After hitting a spiritual low point writing A Confession, Tolstoy underwent a kind of religious reawakening while revisiting the Sermon on the Mount. His new touchstone—that the kind of humility and compassion demonstrated by Christ could not only dispel individual suffering but could also enable the creation of a utopian society on Earth—redefined his appreciation of Buddhist texts. Moving past his previous fixation on the first noble truth, he admired Buddhism’s rejection of violence, which in his mind contrasted unfavorably with the many wars waged by or on behalf of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

A dedicated vegetarian for moral reasons, he also admired how the Buddhist precept of nonviolence extended to animals. Just as certain monks were known to sweep the floor on which they walked to avoid stepping on insects, so did Tolstoy open his third, final, and aptly titled novel Resurrection by describing how a beautiful spring morning was enjoyed by every manner of creature, from human children to flies “buzzing along the walls, warmed by the sunshine.” Tolstoy’s postcrisis conception of the universe, like that of Buddhists, was one in which everyone and everything is connected and interdependent.

Finally, Tolstoy recognized in the stipulations of karmic law the same appeal to selflessness he had found in the New Testament. “Buddha,” he wrote in a letter cited by Milivojevic, “says that happiness consists in doing as much good to others as possible. Regardless of how strange this appears on superficial observation, it is undoubtedly so; happiness is only possible by renouncing the aspiration toward personal, egoistic happiness.”

Just as certain species of bird seek out specific twigs and grasses to build their nests, so did Tolstoy pay attention only to those aspects of Buddhist thought that corresponded to his preconceived framework for an ideal religion. Nirvana—insofar as he understood it—he ignored, along with the concept of reincarnation. The result of his selective process is best illustrated by two essays on Buddhism composed during the final years of Tolstoy’s life: “Buddha” and “Life and Teaching of Siddhartha Gautama Called the Buddha, That Is, The Most Perfect One.” Put simply, these texts are to their source materials what The Kingdom of God Is Within You is to the Bible. Devoid of miracles and idolatry, Tolstoy’s account of the Buddha’s life is indistinguishable from his treatment of Christ’s: historical, concerned almost exclusively with rationality and ethics, its setting more evocative of Yasnaya Polyana than ancient India. A Buddhist reading of Tolstoy, in sum, tells us less about Buddhism than it does about Tolstoy himself. He was indeed a scavenger, but he didn’t scavenge indiscriminately. Even before he began his search, he knew exactly what he was looking for.

KickT

KickT