The fandomization of news

Lil Tay in 2018. | Image: Lil Tay / YouTubeYounger generations expect news to come straight from creators. But when creators are wrong, the news ecosystem quickly breaks down. Continue reading…

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24856993/Screenshot_2023_08_17_at_2.44.31_PM.png)

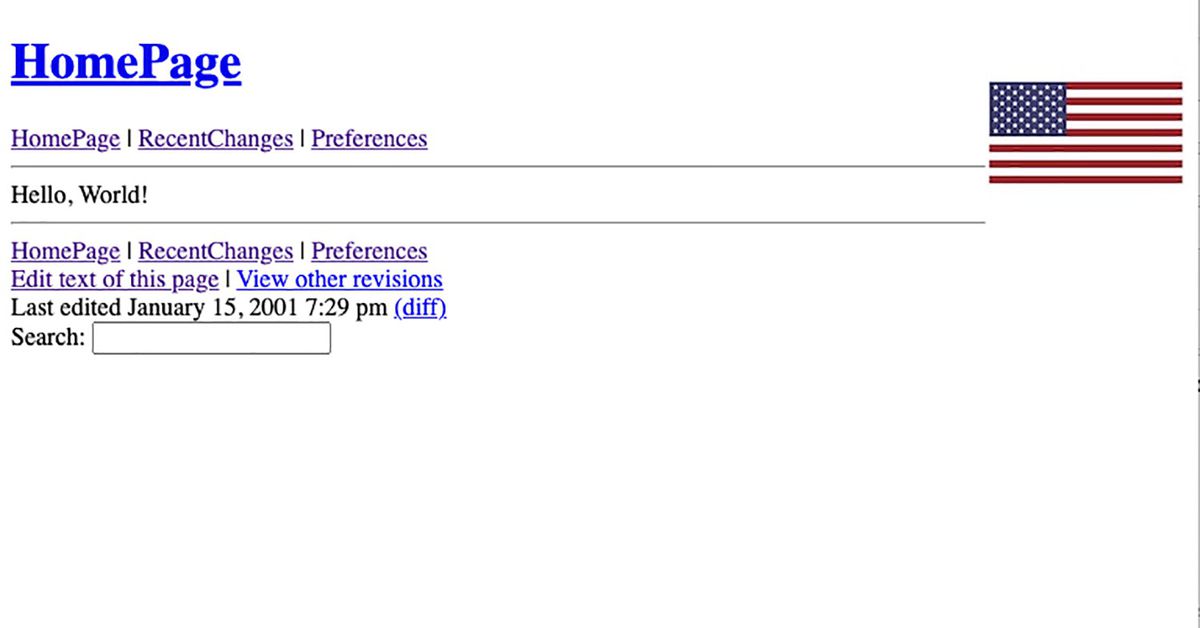

On Wednesday, August 9th, an announcement appeared on the Instagram account belonging to 16-year-old influencer Lil Tay, real name Tay Tian. The message said that Lil Tay, along with her brother, Jason, had suddenly and unexpectedly died.

This was the first time anything had been posted to Lil Tay’s account in five years. While she first went viral in 2018 for her combative and brash personality, she faded back offline after just a few months. The statement was abrupt. But it appeared to come straight from the family, and it was posted directly on the account of the creator herself. Why wouldn’t it be true?

The news exploded across social media, propelled by creators on TikTok sharing and reacting to the Instagram post. Many outlets also ran with the story, some reporting confirmation from an unnamed management team. Then, on August 10th, Lil Tay shared a statement directly with TMZ: both she and her brother were alive. Her Instagram account had, supposedly, been hacked.

The debacle exemplifies how social media has radically changed and complicated the news environment. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok have grown beyond making connections and delivering entertainment into places people trust to keep themselves informed — in part because they can hear stories directly from the source.

A Pew Research Center study found TikTok is where almost a quarter of US adults under 30 now regularly get their news. Another recent study found that influencers are overtaking journalists as the primary news source for young people, with audiences preferring to get their news from “personalities” like celebrities and influencers rather than mainstream news outlets or journalists.

“When there’s no face to it, it seems like it’s a corporation, and corporations to a lot of Gen Z equal bad or untrustworthy,” says Lucy Blakiston, the co-founder behind the Gen Z media company Shit You Should Care About.

Gen Z fell headfirst into the world of influencers forced to report on and police themselves

The shift is particularly acute for Gen Z, who fell headfirst into the world of influencers and other online creators. This generation was raised among digital communities that were overlooked by traditional news outlets and forced to report on and police themselves through makeshift authorities like drama channels. If audiences wanted to hear news or have rumors debunked about their favorite creator, they would have to hear it from the creator themselves or a similar digital primary source.

Members of these communities became adept at a kind of citizen journalism that they now apply to more traditional news, prioritizing a first-person source or someone with relevant experience over the expertise of an unfamiliar journalist or stuffy publication. A recent study by Google’s Jigsaw unit, published alongside the University of Cambridge and Gemic, found this to be the case on TikTok as early as 2018 — the year it debuted in the US — with a participant investigating a rumor that Katy Perry had killed a nun.

“They were disappointed to find no stories from major news sources that definitively answered this question,” the study says. “They went to TikTok and concluded that if Katy Perry fans hadn’t weighed in, the story must not be true. They trusted Katy Perry fans, who engaged with and reported on her activities daily, to know the truth.” (For what it’s worth, what actually happened is a nun involved in a property dispute with Perry collapsed and died in court.)

In other cases, overwhelmed by the sheer number of news sources out there, the study found that Gen Z consumers would rely on a “go-to” source through which they’d filter current events. Often, this was an online personality with similar values.

“There’s a sense of pureness in the independent media landscape,” Jules Terpak, a content creator who covers tech and digital culture, says. “Their audience is witnessing their growth from 0 to 100. The relationship built is far more personal. The underlying trust built is more friend-like.”

In some cases, this system of small creator news works. Reddit was where Try Guys fans first began speculating in fall 2022 that now-former Try Guy Ned Fulmer had cheated on his wife with an employee. This was based on firsthand accounts from fans who had spotted Fulmer and the employee at a concert as well as clues that suggested Fulmer had been cut out of recent videos. After a few weeks of this discussion, the Try Guys confirmed the affair and that they had parted ways with Fulmer.

In other cases, the system can fail in unfortunate ways. Celebrity gossip account Deuxmoi took off during the pandemic for the account owner’s claims to have inside information that traditional media wouldn’t report on. The account has over 2 million followers and is often the source of rumors that traditional outlets then chase. But often enough, those rumors turn out to be wrong. Most notably, during the midst of the search for the missing submersible in June, the account posted — and later deleted — an anonymous tip that all five passengers had been found alive. Two days later, US Coast Guard officials announced that the passengers had instead all died within the first few hours of the trip.

Influencers are becoming aware of their role in the news cycle, for better or for worse. Recently, creator Dani Carbonari went viral for referring to herself as an “investigative journalist” while on a Shein-sponsored trip to one of their factories. Carbonari used her now-deleted video to “debunk” legitimate reports of Shein’s labor violations, which include subjecting workers to 12–14-hour days and permitting just one day off a month. When called out for the impartiality of reporting on a company that is, in fact, sponsoring and dictating the entire reporting trip, Carbonari doubled down.

The spread of misinformation is often blamed on the tech illiteracy of boomers, but Gen Z’s enthusiastic use of social media can give false stories exponentially bigger reach.

In February 2022, Terpak covered how Gen Z accidentally spread a false narrative about athlete Sha’Carri Richardson. Richardson was unable to compete in the Tokyo 2020 Olympics — held in 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic — after receiving a 30-day suspension after testing positive for THC; meanwhile, Russian figure skater Kamila Valieva similarly tested positive for a banned heart medication ahead of the 2021 Winter Olympics in December but was allowed to compete. Richardson and others were quick to point out how race may have played a role in these seemingly contradictory rulings, and an Instagram infographic posted by Gen Z political nonprofit Path to Progress ran with it. The post was shared by thousands of people, motivated by a sense of social justice.

In reality, as Terpak points out in her video, the reason for the different rulings came down to age. Valieva was 15 at the time, making her a protected person under the world agency’s doping code.

“Though the comments were full of people calling out the inaccuracy of this content, who looks at Instagram comments of these types of accounts?” Terpak asked in the video.

For current adolescents, schools are making an effort to address this problem, but it’s not standardized and can be out of touch.

“It’ll be like, ‘don’t trust Wikipedia,’” Laura Hazard Owen, editor of Nieman Journalism Lab, says. “That’s not good advice. Wikipedia is a great source to start with.”

Blakiston’s Gen Z-focused media company, Shit You Should Care About, is careful to use only legitimate sources in their daily newsletter, linking to the established news outlets their 77,000 readers likely wouldn’t pore through themselves. Blakiston leans heavily on personality to maintain that trust with younger readers and to prevent ever seeming too much like news with a capital N. Every dispatch begins by addressing the readers as “lil shits” and is written informally in the first person. But that intimacy can be a double-edged sword, especially when the person Gen Z readers trust to curate news for them lets them down. If their followers disagree with the news Blakiston chooses to highlight, the backlash can get personal.

“It changes the way and the place that we cover things,” she says. “For anything that requires heavy nuance, I won’t even go near Instagram.”

The social media news machine also emerged from the ashes of a decimated traditional news ecosystem. In 2022, Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications found that local news outlets were folding at a rate of two newspapers a week. The media industry announced more than 17,000 cuts in the first half of 2023, the highest year to date on record. Cable news also saw a drop this year, one that isn’t likely to dramatically reverse, as only 6 percent of Gen Z claim to watch cable news daily, and 48 percent claim they never watch it at all.

Internal struggles aside, the choppy and competitive waters of today’s news environment mean, like in the case of Lil Tay, outlets can similarly get duped, losing readers’ trust and driving them back to the creator ecosystem. “Often news organizations do make bad decisions,” Owen says. “You can sometimes feel like you’re in this murkiness of ‘Oh my God, I can’t trust anything,’ which is such a dangerous place to be.”

The only thing standing between true and false might be one single creator.

V Spehar, the TikToker behind Under The Desk News, didn’t have a journalism background when they first joined TikTok and planned to use it as a place to post culinary videos. But their quick takes on day-to-day news items ended up winning them an audience, and they now have 3 million followers tuning in for their daily political updates filmed, as the name suggests, under a desk.

The Los Angeles Times took note of V’s success and tapped them to help launch its own personality-based TikTok account. They’re one of many publications attempting to recreate the success of individual creators on TikTok within their newsroom. The Washington Post’s account shot to fame in 2019 thanks to host Dave Jorgenson’s irreverent reimaginations of the news and has since earned over 1.6 million followers and added a handful of additional hosts, including Carmella Boykin and, most recently, Chris Chang.

Chafe as legacy media might, Gen Z is giving them no choice but to adapt — or get lost in the algorithm. Google’s Jigsaw study found that young news consumers were reluctant to proactively sift through information. One participant said he felt no need to search or follow news and politics.

“When stuff is important,” he said, “it gets shared.” As long as it’s not legacy media doing the sharing.

KickT

KickT