The First Studies on Vegetarian vs. Meat-Eating Athletes

Meat-eating athletes are put to the test against vegetarian athletes and even sedentary plant-eaters in feats of endurance. “In 1896, the aptly named James Parsley […]

Meat-eating athletes are put to the test against vegetarian athletes and even sedentary plant-eaters in feats of endurance.

“In 1896, the aptly named James Parsley led the Vegetarian Cycling Club to easy victory over two regular clubs. A week later, he won the most prestigious hill-climbing race in England….Other members of the club also turned in remarkable performances. Their competitors were having to eat crow with their beef.” Then, a Belgian researcher put it to the test in 1904 and found that those eating more plant-based reportedly lifted a weight 80 percent more times. (I couldn’t find the primary source in English, though.) I did find a famous series of experiments at Yale, published more than a century ago, on “the influence of flesh eating on endurance,” which I discuss in my video The First Studies on Vegetarian Athletes.

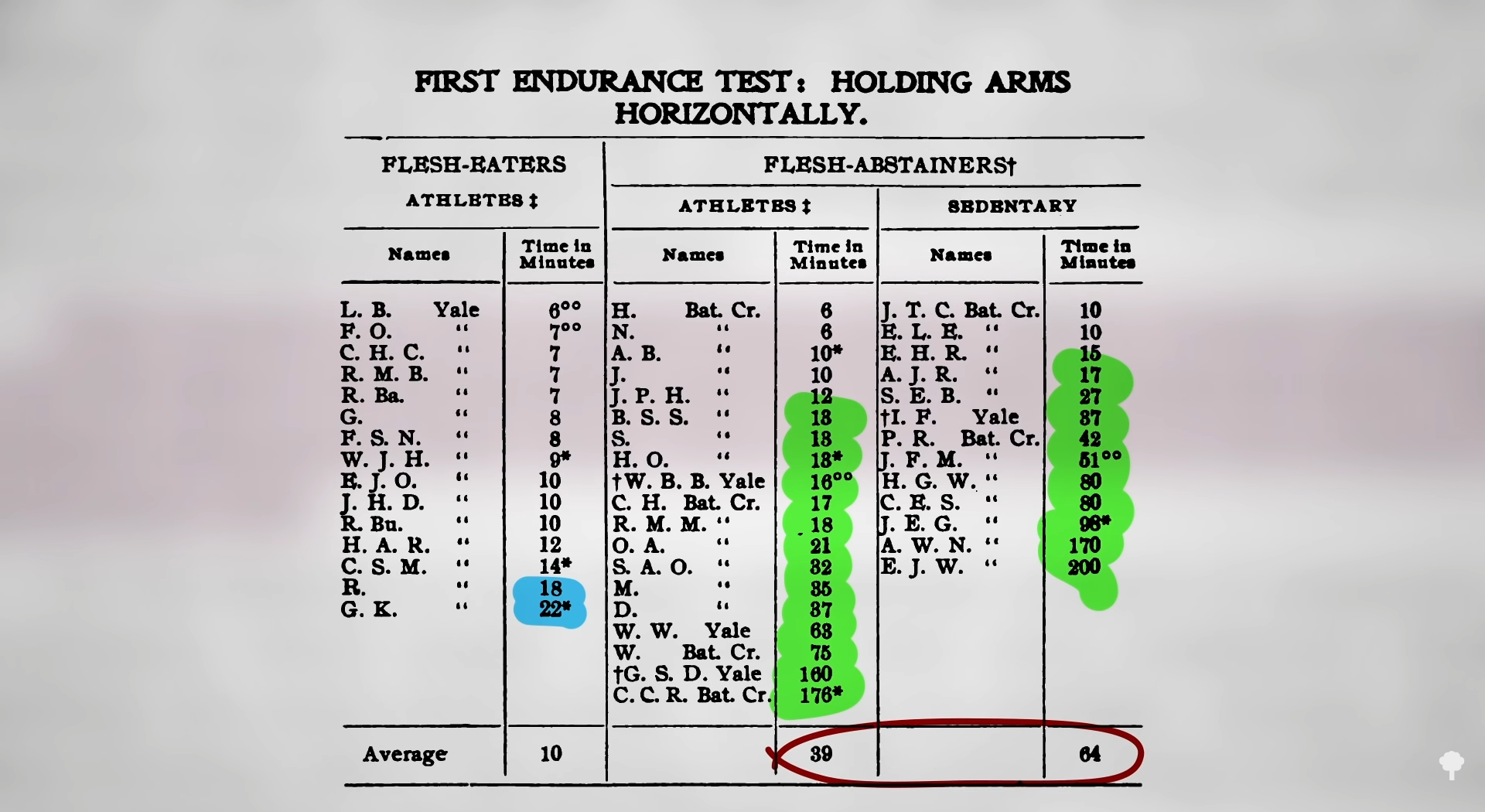

The Yale study compared 49 people: meat-eating athletes (mostly Yale students), vegetarian athletes, and sedentary vegetarians. “The experiment furnished a severe test of the claims of the flesh-abstainers.” And, “much to my surprise,” wrote the researcher, the results seemed to vindicate the vegetarians, suggesting that those eschewing meat “have far greater endurance than those who are accustomed to the ordinary American diet.”

As you can see at 1:12 in my video, the first endurance test measured how many continuous minutes the participants could hold out their arms horizontally: “flesh-eaters” versus “flesh-abstainers.” The meat-eating Yale athletes were able to keep their arms extended for about ten minutes on average. (It’s harder than it sounds. Give it a try!) The vegetarians did about five times better. The meat-eater maximum time was only half the vegetarian average. Only two meat-eaters hit 15 minutes, while more than two-thirds of the meat-avoiders did. None of the meat-eating athletes hit half an hour, while nearly half of the plant-eaters did. This included nine who exceeded an hour, four who exceeded two hours, and one participant who kept going for more than three hours.

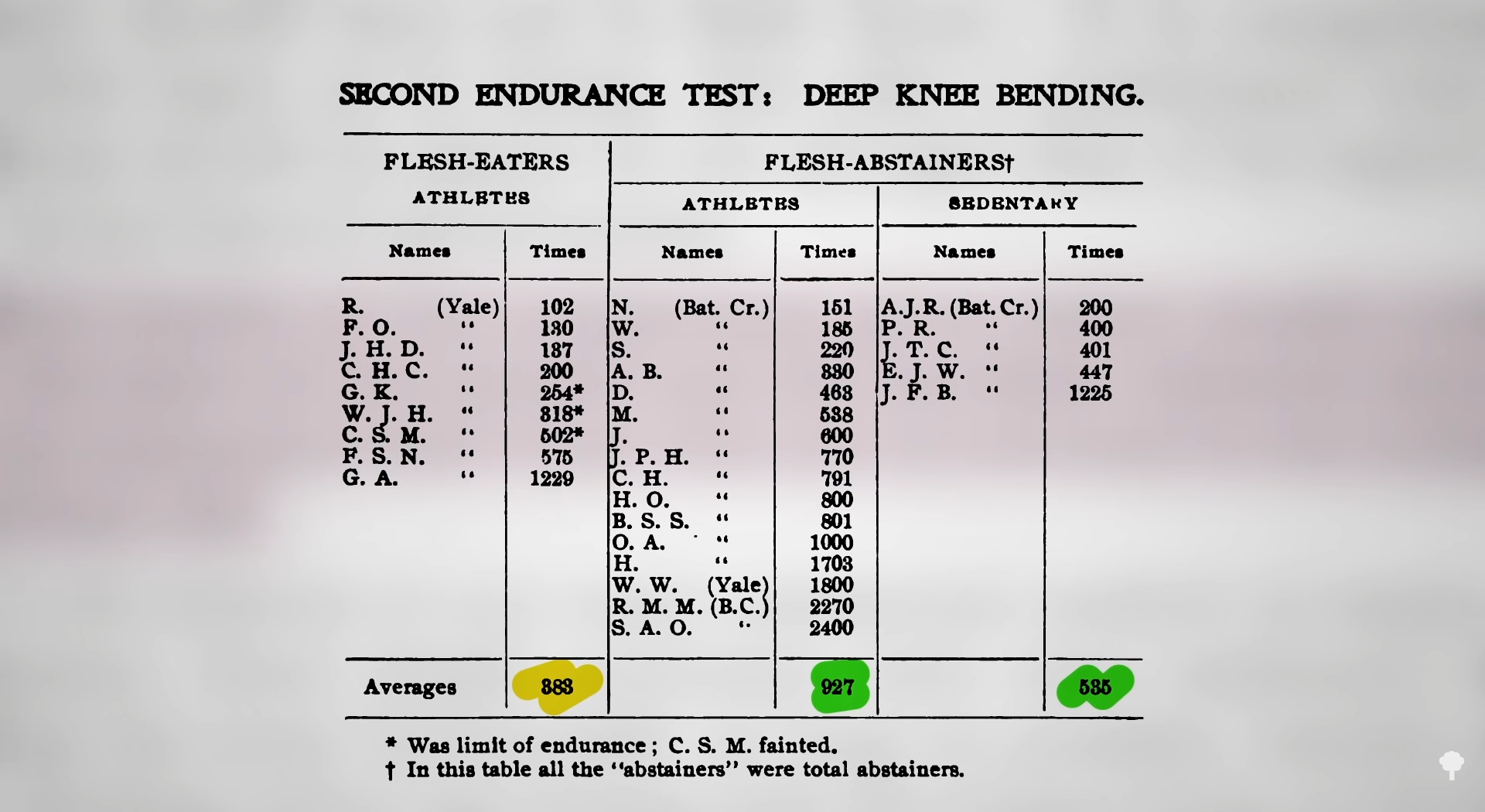

How many deep knee bends can you do? One meat-eating athlete did more than 1,000, with the group as a whole averaging 383, but the plant-eating athletes creamed them, averaging 927. Even the sedentary vegetarians performed better than the meat-eating athletes; they averaged 535 deep knee bends. That’s wild! “Even the sedentary [meat] abstainers surpassed the exercising flesh-eaters” in performance. In most cases, the sedentary plant-eaters were physicians who sat on their butts all day. I want a doctor who can do a thousand deep knee bends! As you can see at 2:15 in my video.

Then, in terms of recovery, all of those deep knee bends left everyone sore, but much more so among those eating meat. Among the vegetarians, of the two who did about 2,000 knee bends each, one went straight off to the track to run and the other went on to their nursing duties. Among the meat-eaters, one athlete “reached his absolute limit at 254 times, and was unable to rise from a stooping posture the 255th time. He had to be carried downstairs after the test, and was incapacitated for several days.” Another meat-eating athlete was impaired for weeks after fainting.

“It may be inferred without reasonable doubt,” concluded the once skeptical Yale researcher, “that the flesh-eating group of athletes was very far inferior in endurance to the abstainers,” the vegetarians, “even the sedentary group.” What could account for this remarkable difference? Some claimed that flesh foods contained some kind of “fatigue poisons,” but one German researcher who detailed his own experiments with athletes offered a more prosaic answer. In his book, Physiologische Studien über Vegetarismus—looks like Physiological Studies of Uber-Driving Vegetarians, doesn’t it? (I told you I only know English)—he conjectured that the apparent vegetarian superiority was due to their tremendous determination “to prove the correctness of their principles and to spread their propaganda.” If we believe him, vegetarians apparently just make a greater effort in any contest than do their meat-eating rivals. The Yale researchers were worried about this, so “special pains were taken to stimulate the flesh-eaters to the utmost,” appealing to their college pride. Don’t let those lousy vegetarians beat the “Yale spirit”!

The Yale experiments made it into The New York Times. “Yale’s Flesh-Eating Athletes”—sounds like the title of a zombie movie so far, doesn’t it?—“Beaten in Severe Endurance Tests.” “Prof. Irving Fisher of Yale believes that he has shown definitely the inferiority in strength and endurance tests of meat eaters to those who do not eat meat…Some of Yale’s most successful athletes took part in the strength tests for meat eaters, and Prof. Fisher declares they were obliged to admit their inferiority in strength.” How has the truth of this result been so long obscured? One reason, Professor Fisher suggested, is that vegetarians are their own worst enemy. In their “vegetarian fanaticism,” they jump from the premise that meat-eating is wrong—“often bolstered up by theological dogma”—to meat-eating is unhealthy. That’s not how science works. Such leaps in logic get people dismissed as zealots, “preventing any genuine scientific investigation.” A lot of science, even back then, was pointing to “a distinct trend toward a fleshless dietary,” towards more plant-based eating, yet the word vegetarian, even 110 years ago, had such a bad, preachy rap “that many were loath” to concede the science in its favor. “The proper scientific attitude is to study the question of meat-eating in precisely the same manner as one would study the question of bread-eating” or anything else.

ValVades

ValVades