The Present Tense: Poet Laureate Ada Limón

Poetry, like meditation, isn’t about doing or accomplishing. It’s about feeling what it means to be alive, in this moment. Lion’s Roar’s Mariana Restrepo talks with the poet laureate Ada Limón. The post The Present Tense: Poet Laureate Ada...

Mariana Restrepo: You don’t consider yourself a Buddhist. However, you often talk about Buddhist concepts as well as your meditation practice. Can you tell us how you first encountered Buddhism and meditation?

Ada Limón: My meditation practice changed my life. When I started meditating, I recognized my own mortality and the urgency of my own life for the first time. Because of that, I chose art.

Around 2007, I started meditating and learning about meditation in earnest. I was living in New York City, struggling with how to be at ease in the world, and it felt like I could never get to a place where there was any semblance of peace in my body and mind. I was desperate for something that would give me what I now call equanimity; maybe then I would’ve called it spaciousness.

I went to Tibet House in New York City. Sharon Salzberg was teaching on loving-kindness and mindfulness meditation. I remember feeling a shift in me and realizing, “Oh, this is what I’ve been missing.” We usually live in the past or in the future and don’t recognize the present. This concept was completely obvious to me, and yet it wasn’t until I heard it said out loud and articulated that I recognized it as one of our most important truths. Cultivating awareness of the present is a key foundation for not just who I am as an artist, but who I am as a human being.

How has your meditation practice influenced your poetry and creative process?

One of the biggest influences it has had on me is that I am now able to name the wanting, the desire, the mind that is always aching for something else.

Before, I did not know how to write a poem in the present tense. Now I’m very at ease in the present—I know what it is. Many of my poems in The Carrying, Bright Dead Things, and most recently, The Hurting Kind are poems in the present tense. Those, in many ways, came out of meditation, or they are themselves a form of meditation—of being present and observing and paying deep attention to the world around me.

Being aware of the present moment not only shifted, but also deepened my relationship with my work. I could see poetry’s importance in my life as an essential medicine. With poetry entwined with my meditation practice, my poetry became even more foundational to my life. Poetry became a way of meditating. My meditation practice and my poetry practice became significant collaborators.

You are the first Latina poet laureate of the United States. What has that meant to you, and how has that influenced your poetry?

The first is always a difficult thing to be, because you can’t help but think, “Why is that?” It’s a beautiful honor, but it’s also tinged with the sadness of our relationship to Latinx culture, our relationship to the representation of Mexican Americans and all Latinx folks in the United States. So, being the first is both beautiful and disheartening.

Photo by Ayna Lorenzo / courtesy of John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Photo by Ayna Lorenzo / courtesy of John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur FoundationI’ve always been a little distrustful of “we.” When people say “we” in their art, speeches, rhetoric, or in their public statements, I have always questioned if I, my family, and other Latinx folks are part of that “we.” When I write, I’m always looking to represent not necessarily a “we,” but an “I” that establishes a voice for people who may not have had representation in some of these larger literary spheres.

You have talked about how you feel you are honoring your ancestors through your poetry, especially since your grandfather, as an immigrant, did not have the chance to choose art. What was your grandfather’s experience, and how do you honor your ancestors through poetry?

As an immigrant, a big part of my grandfather’s life was working toward survival. It’s hard to be an artist when you’re worried about your safety, well-being, health, and security. I feel very grateful and lucky to have the gift of my family. Their support gave me the safety to be an artist. They rooted me on. I feel like I am not only honoring my grandfather’s memory—Francisco Carlos Limón from San Juan de Los Lagos in Jalisco, Mexico—I’m also lifting him up. I’m giving him an opportunity to be an artist through me. And that might sound a little strange, but it feels like he didn’t get that chance because everything was about keeping a foothold. So, because of that, I don’t take my chance for granted.

How does poetry help people process the trauma they’ve experienced? How does it help people connect with their humanity and the natural world?

Poetry can do many things. Part of it can be about connection and healing, some of it can be about disruption, and some of it can be about disturbance and dissonance. It’s like when you’re meditating. You have a moment that feels at ease, and you think, “Oh, I just found it.” But when you have a moment that feels immediately painful, that’s just as useful. Both are good teachers. Poetry can also do both things. It can allow us to heal because we’re working through something, but it can also allow us to recognize what we’ve been through and honor that grief.

One of the things that we don’t do very often is make enough time for grief. Often, it’s so difficult that we just move through it, bypass it. People have a difficult time talking about where we are right now with the planet—the climate crisis or the global human crisis. It’s because we can’t handle the grief. Poetry can be a way of not just connecting to the planet, but connecting to that feeling of grief, connecting to the unease of difficult truths, as well as connecting to beauty and wonder.

How can all those things exist at once? The truth is they do. We can be scared and fearful and angry, and at the same time we can feel great curiosity and awe and wonder at the natural world. Poetry is a place where you can hold all those things. You don’t have to choose one or the other. Instead, all of those things can exist. That’s one of the reasons I find poetry useful. I hate to say “useful,” but it’s useful because it feels like a container that is our universe ever-expanding.

When you talk about poetry in this way, are you referring to creating poetry or reading poetry?

Thank you for asking me that. Writing poetry can be a very important way of excavating everything that’s been unsaid. But receiving a poem—whether it’s reading it, listening to it, or even just reading one line and not finishing the poem—it brings you someplace else. Reading poetry offers a beautiful connection to the strange human language that we’ve made, that we have.

Poetry can be not just a way of processing, but also a way of offering ourselves permission to slow down and feel something. In today’s day and age, we’re not really allowed to feel anything. We’re allowed to do. We’re allowed to accomplish. We are allowed to check things off a list. Poetry doesn’t have anything to do with that. Poetry wants you to feel, it wants you to recognize your place in the world. In that sense, it’s very similar to the act of meditation.

There’s nothing to accomplish, right? There’s no goal in meditation or poetry.

And there’s no right answer. Poetry is not looking to be solved. It’s like the breath; it’s made of breath, and because of that, all it wants is to be experienced.

You’ve said that poetry gives us a way to “reclaim our humanity,” and that it can help repair our relationship with the planet. Can you talk about how poetry does those things, and how you share that vision through your own poetry?

It goes back to the idea of the danger of repressing our feelings, the danger of repressing our connection to others and to the earth, which sometimes we’ve had to do to survive. We compartmentalize to get through the day. We’ve done it on such a large scale that we’ve forgotten the great ecological harm that we’re part of causing. Poetry, whether it’s the writing or the reading of it, can really give us a way of paying attention to the things we’ve missed, to recognizing the connections.

When we look at birds, we notice them. One of the great things that we don’t talk about enough is that birds also notice us. We are in relationship with nature on a daily basis. We’ve become so separate from it that how can we grieve it? How can we protect it if it feels like we’ve set up a great barrier, a great distance between us and the natural world, not recognizing that we are animals? We are human animals, and we are part of this ecosystem. We are part of this reciprocal nature. We’ve come so far from the natural world that we need many, many tools to reignite our senses to that connection.

Poetry is one way of doing that. Meditation is another way. Poetry does this because of the way that one line can ground you, and it brings deep noticing, and that deep noticing is a way of loving. It feels like it is almost a political act to notice the world; it’s an emotional act to notice the world. The more we do it, the more human we become. I mean human in the best way: in its vulnerabilities, in its messiness, in its chaos. We just need to make more and more room for that feeling, for that connection.

You Are Here, a poetry anthology that you edited, was recently released. In the introduction, you write, “poetry and nature have a way of reminding us that we are not alone.” This reminds me of the Buddhist concept of interconnectedness. Can you talk more about that sense of communion, that interconnectedness, and how it’s expressed throughout the poems you selected for this book?

One of the things that people keep talking about as a real global issue is loneliness—there are so many people who are lonely. If I’m lonely, I can look outside and look at birds. I can look at a tree, a plant, the grass, and feel like I’m not alone. I can feel like, “Oh, you’re trying to do something, you’re trying to grow. I’m also trying to live—we have that in common.” That might be very small and minute, but it has saved me again and again from deep depression, from really feeling isolated from others, from feeling like no one would ever know me.

When I chose the poets to write poems for You Are Here, I knew they were people who were not just great poets—they were also deep thinkers and believers in the planet. When they sent in the poems, I had a moment when I was putting together the book where I spread all the poems out on the floor all over my house. The whole house was covered in beautiful poems. I thought it was the perfect example of interconnectedness. These poems were speaking to each other. It was a beautiful experience. It felt like a tree, like a root system. When we think about that idea of interconnectedness and that sense of not being alone, what those poems offered me that night felt otherworldly in some way. I really hope that other people feel that same way when they read the book.

You have asked readers to consider writing their own “you are here” poem, a poem that keeps us grounded amidst constant change, a poem that connects us to the natural world. Where can readers submit their poems?

I would love for people to be part of that collection and write a poem and share it on whatever social media platform they use with the hashtag #YouAreHerePoetry. I’m hoping that a hashtag will help bring everyone together. But someone could also just write a poem and burn it in their burn pile if they want, or they could write it on shells or rocks by the creek bed and let it get washed away. Sometimes what’s important is not just the making of a thing or the sharing of a thing or the recognizing of a thing, but the impulse to speak back to the world.

Two Poems by Ada Limón

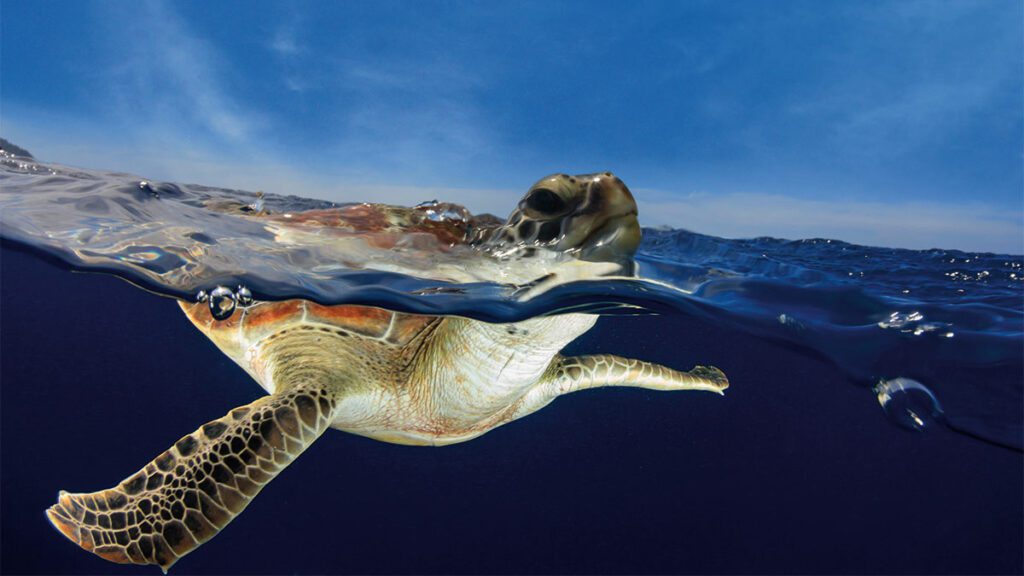

Photo by Richard Carey / stock.adobe.com

Photo by Richard Carey / stock.adobe.comSea Turtle

First it was a rock

then not a rock at all.

First there was only water

then shadow pushing

against water—then

a head, a front fin,

the hard carapace,

and together we

were swimming, at ease,

no hurry, no rules.

Later, I pretended he

saw me, that he was closer

than he was. It is in my

nature to tell stories,

to tell you what he meant

serene and excellent

and how he mirrored my

desire with a sort of un-desire

but what is more true

is that I laughed, ridiculous

joy, seeing his head arise

and disappear and arise

again. Joy didn’t feel heavy

enough for such a stately

creature of ages. I kept

my distance and laughed

and pointed and was full

of surprise and the best part?

Every sound I made

disappeared in the waves

Mortality

When a poet says, “Let me

be clear,” we are never clear.

Big drops on the palm fronds

and a fat moon under clouds.

Language, I love it, but it is of the air

and we are of the earth.

I want you to know this image—

plumeria wet and swaying,

but only the sound of a door

closing in an empty room comes,

something beginning and ending

without so much as a warning.

Mariana Restrepo is deputy editor of Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Guide (published by Lion’s Roar). She is Colombian with a Nyingma-Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist background, has an MA in Religious Studies, and currently lives in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina with her husband and two children.

Ada Limón is the twenty-fourth Poet Laureate of the United States. She’s the author of several poetry collections, including The Carrying, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, and Bright Dead Things, a finalist for the National Book Award.

Lynk

Lynk