Honoring Those Who Came Before Me

Alisa Dennis on why she honors ancestors—spiritual and biological, human and animal, water and wind. The post Honoring Those Who Came Before Me appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

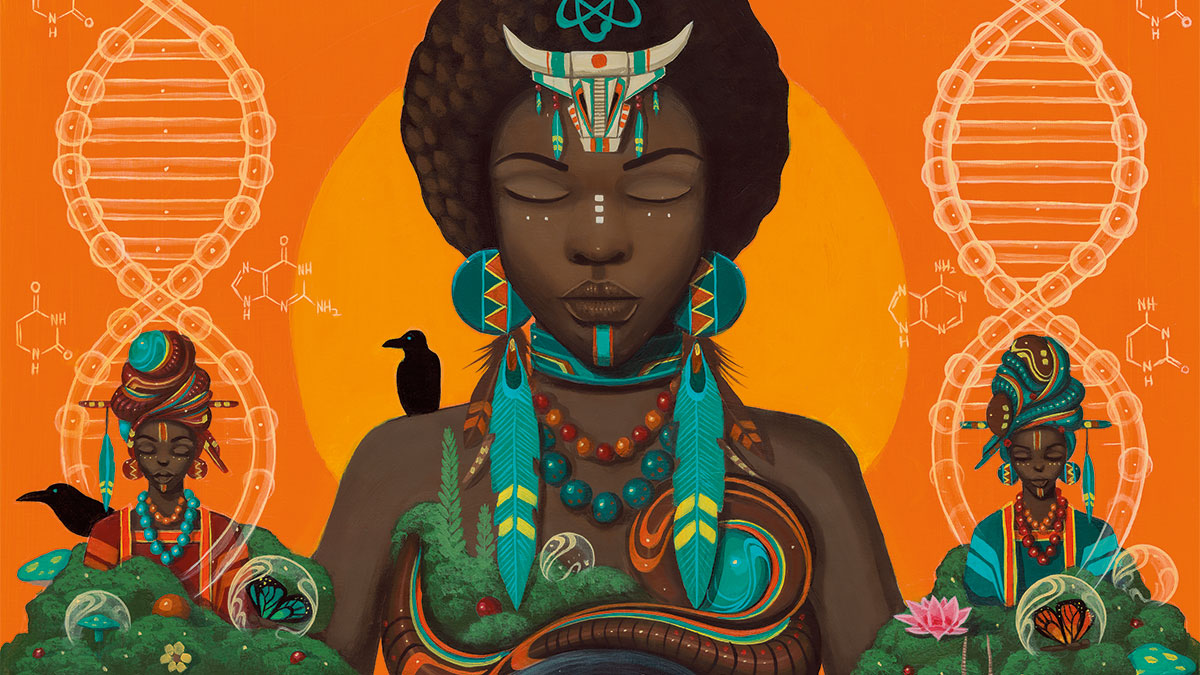

The personal pronouns I use are she/her/they/we. My use of rolling pronouns is representative of my identification with a fluid spectrum of gender expression as well as my spiritual awareness that I’m composed of both feminine and masculine qualities. The “we” is a nod to my ancestors, those who’ve come before me, and those who will come after me.

“We” represents my knowing that my ancestors are an integral part of who I am. They’re in my bones, breath, blood, in the warmth or coolness of my body, in the space within me and outside of me. “We” is an acknowledgment of the truth of interbeing and no-self.

“At the molecular level, my ancestors are a part of me.”

Lyrical Zen, a collective of spiritually oriented multimedia artists who create content to inspire human enlightenment, offers Ancestral Mathematics. It’s a way to calculate how many ancestors had to exist in order for us to be born. According to their math, 4,094 ancestors across twelve generations are required for any one of us to come into existence.

At the molecular level, my ancestors are a part of me—a part of this fathom-long body and a part of the emptiness from which all creation flows and returns. Thich Nhat Hanh once said, “If you look deeply into the palm of your hand, you will see your parents and all generations of your ancestors. All of them are alive in this moment. Each is present in your body. You are the continuation of each of these people.”

Our ancestors aren’t just those with whom we share DNA. We are also the continuation of those who loved, cared for, guided, and nourished us, such as our schoolteachers and coaches, godparents, friends, and more.

Besides our human ancestors, we might also consider other forms of life as our ancestors. We have prehuman and nonhuman ancestors: the earth, the oceans, lakes, and streams, the wind, the lightning, trees, the stardust, and creatures, great and small—these too are our ancestors. After all, they have shaped us.

We also have land ancestors. Do you feel gratitude for the lands you are on and for the people who stewarded them and their descendants? Give thanks for their care and the ecological practices and values that so many in the West are now turning toward to find balance and harmony in our relationship with the earth.

In Buddhist traditions, our ancestors are the teachers who came before us, who transmitted teachings and practices over thousands of years. These teachers knew they were responsible not only for their own liberation, but also for the liberation, peace, and freedom of future generations. Understanding interconnectivity across time and space, they knew the importance of keeping the teachings alive. Without this transmission, we wouldn’t be here today learning, practicing, and teaching the dharma.

Most of my Zen, Insight, and secular mindfulness teachers have been Westerners, but their teachers were mostly from Asia. For those practicing Western convert Buddhism, it would be wise to acknowledge the enormous generosity and goodwill of the Buddha in dedicating his life to teaching and the many generations of Asian teachers who transmitted his teachings. I honor all my teachers, including the Asian teachers of my teachers. I also honor the Asian American Buddhist communities in the West who were the first to bring Buddhism to America and who have been sharing the dharma right alongside the white and Western teachers all this time.

Our ancestors don’t only include those who invoke positive feelings. Sometimes including ancestors in our practice of remembering may activate old traumas. When we reflect upon those ancestors who perpetrated harm against us or others, we may feel aversion, anger, and shame.

When I’m leading a practice of ancestor contemplation, I invoke the presence of “well-ancestors” or “ancestors of your choosing,” encouraging people to call in ancestors with whom they feel safe. We must be mindful to not force an honoring, but to gently feel into what can be named, included, and integrated with minimal harm or discomfort.

Sometimes we might feel an aversion toward particular people in our ancestral lineage; however, the nature of reality is holographic. As we deepen our understanding of this truth, we learn that it’s not possible to separate ourselves from them. The wounded part of us reflects the wounded part of an ancestor who may have caused harm. When we heal that wound in ourselves, we also heal it in them. When we offer appreciation, loving-kindness, compassion, or forgiveness to them, we support the healing of their woundedness, as well as our own.

I was introduced to the importance of honoring ancestors long before I became an Insight practitioner. In my practice of African and Mayan shamanism, ceremonial ways of revering ancestors involved creating ancestor altars and giving offerings to them. As a member of a Daoist temple, I practiced bowing and incense burning rituals paying homage to Daoist ancestors. In my Zen training, everything we did was a sacred ritual, and honoring generations of Zen teachers was one part of our daily practice.

Honoring my own maternal and paternal ancestors, as well as the lineage holders and teachers of the dharma, is an integral part of my daily meditation practice. I don’t necessarily feel compelled to create an elaborate ritual to honor them. My felt sense of them in my being is enough.

One way you can cultivate a felt sense of your ancestors is to set the intention when you meditate that you’re not just meditating for yourself, but also for all beings, including your ancestors. Taking a few breaths, contemplate how your ancestors don’t live outside of you somewhere else; they live inside of you and are a part of you. Then take a few moments to express gratitude and appreciation in whatever way expands your heart. The Sanskrit word kritajna is usually referred to as “gratitude,” but its literal translation is “to carry the memories of the favors that have been received by us.”

One of my favorite Buddhist texts is the Avatamsaka Sutra, with its resplendent, dazzling imagery and the metaphors it uses to convey interbeing and the multidimensional nature of reality. This sutra teaches that there are infinite Buddha worlds and bodhisattvas on the tip of a blade of grass and that each one of us exists within each one of us, which confirms that our ancestors live within us and we within them at every moment. Whenever I meditate or chant, I embody the truth of interbeing since I am meditating and chanting for all my ancestors. There is no separation.

A teacher at Insight LA and Spirit Rock, Alisa Dennis is a licensed clinical psychologist in private practice.

ValVades

ValVades