This Fresh Existence: Heart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhammananda: Book Excerpt

An Excerpt from This Fresh Existence: Heart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhammananda by Cindy Rasicot I am not exactly sure when it happened, but it was most likely the summer of 2016 – a very hot day at Venerable Dhammananda’s monastery...

Bhikkuni Dhammananda

Bhikkuni Dhammanandaby Cindy Rasicot

I am not exactly sure when it happened, but it was most likely the summer of 2016 – a very hot day at Venerable Dhammananda’s monastery in Nakhon Pathom. All the nuns and laywomen had gathered near the front wall of the temple for the afternoon work session. There was a mound of soil that Venerable Dhammananda had asked us to remove and transfer to the back garden area.

I was sweltering under the Thai sun and not in the mood to be shovelling earth from one place to another. The task seemed senseless. Women lifted hoes and pickaxes, chipping away at the mound, inching their way forward bit by bit, leaving chunks of semi-dry earth and rock. Several of us followed with shovels and plastic buckets to haul their debris away. We stood side by side in an assembly line, passing the buckets from hand to hand until they reached the last person, who dumped the contents into a large wheelbarrow.

The sweat dripped from my face as my resentment grew. Why do I have to do this? Just then, Venerable Dhammananda stepped forward, hoe in hand. She lifted the tool above her head and with a mighty blow brought it down, smashing the earth to pieces. I was stunned. She was remarkably strong for a person in her early seventies. For me, that single blow symbolized the strength of her determination.

Venerable Dhammananda, previously known by her lay name, Dr Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, did not begin to think seriously about being ordained until her mid-fifties. At the time she had enjoyed a highly successful career as a professor of Buddhist studies for twenty-seven years at Thammasat University, was a well-known media personality who hosted a popular TV dharma show, and had been married for thirty years with three adult sons. She claimed the ‘DNA for ordained life’ was ‘in her blood’ and is proud of her ancestors. Her maternal grandmother, Somcheen, was illiterate but in her later years was ordained as a mae chi and became leader of the temple women at Wat Theravada nun in Thailand in 2003. She had to travel to Sri Lanka to do this because Thailand does not permit women to be ordained. At the time, Thailand had approximately 300,000 male monks and no ordained women, leading the Thai press to dub her the ‘Rebel Monk’. She said, ‘I never felt like a rebel. I simply did what the Buddha allowed me to do, which was to be ordained. I was waiting for others to ordain. In fact, I went to a few other women who I thought might be interested in joining me, but they were not, so I went ahead and did it alone.’

Cover of This Fresh Existence

Cover of This Fresh ExistenceHeart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhamananda by Cindy Resiscot

As mentioned previously, in the context of Thailand’s history as a nation, the lineage of female monastics – samaneris (female novices) and bhikkhunis (fully ordained nuns) – never took hold. Venerable Dhammananda saw it as her responsibility to introduce this missing heritage that the Buddha had granted women. She knew from her academic studies that the history of the bhikkhuni sangha in Thailand occurred in three waves. The first attempt to establish a bhikkhuni order began in 1928, when Narin Phasit (1874–1950) arranged for his daughters Sara and Chongdi to be ordained. Originally, they were ordained as samaneris, but eventually Sara, the eldest, became a bhikkhuni. Narin had been a successful provincial governor early in his career but became disillusioned with the system. He was an embattled public figure, known for his outspoken criticism of the government and the Thais. His calls for political and religious reform landed him in jail several times. He spoke about the importance of establishing a bhikkhuni order for many years before his daughters’ actual ordinations took place and wanted to restore the missing link in the Buddha’s fourfold community of laymen, laywomen, bhikkhu, and bhikkhuni.

The exact details of where or how Narin’s daughters were ordained – even which monks ordained them – were unclear because the event was done in secret. According to Narin’s later account the ceremony took place in April of 1928. Following this, the sisters lived in Nonthaburi province along the banks of the Chao Phraya River at Narin’s elaborate family compound. Part of the living arrangement was designated as a monastery for women, called Wat Nariwong. Venerable Dhammananda indicated there were ‘six other nuns living alongside the two sisters at the monastery’.8

Narin’s attempt to ordain his daughters was not successful. Two months after the ceremony was performed, the Supreme Patriarch (religious head of the Thai Buddhist sangha appointed by the King) issued a decree prohibiting monks from giving ordination to women. The decree, known as the 1928 Sangha Act, proclaimed that bhikkhunis must be present to ordain the women, otherwise ordination was not possible.

The nuns living in Narin’s compound apparently remained in robes for more than a year despite the decree, but at some point they were spotted on their morning alms round. In September of 1929 government officials intervened, and all eight women were put on trial. During the hearing the women were told that by claiming to be ordained and putting on robes similar to those of monks, they had engaged in an act that ‘disgraced the religion’.9 They were asked to disrobe. Four of them complied, but Chongdi was among the nuns who refused. The convicted women ‘fought off a group of prison guards and female inmates deployed to carry them off to prison’.10 Eventually they were imprisoned and forced to disrobe.

The 1928 Sangha Act, often referred to as ‘the bhikkhuni ban’, is still cited by the Thai government in upholding the country’s refusal to accept ordained women. In Thailand the Thai sangha is closely linked to the government. In The Bhikkhuni Lineage, a pamphlet Venerable Dhammananda wrote in 2004, she referred to the Sangha Act as the ‘first structural violence against women, in black and white’, because, essentially, it ‘defined Sangha as only (being) a community of monks’.11

Venerable Dhammananda gained valuable insights from Narin’s failed attempt. The fact that he conducted the ordination in secret was cited as a problem because no one knew if the required number of bhikkhus was present. There may have been only one bhikkhu present to give ordination, in which case it was not done properly in accordance with the Vinaya – the rules and procedures that govern the Theravada Buddhist sangha. By the time Venerable Dhammananda decided to receive full ordination, she knew it would have to be done in public, and with a minimum of five bhikkhus present.

Footnotes:

8 Bhikkhuni Dhammananda, The Bhikkhuni Lineage, first published as a paper pamphlet, Nakhon Pathom 2004, p.12.

9 Sri Krung, ‘Aiyakan forng nen phu-laew’ (Prosecutor Files a Case Against Female Novices), 6 September 1929, from National Archives R7 M26.5/248. This citation is taken from Varaporn Chamsanit, ‘Reconnecting the Lost Lineage: Challenges to Institutional Denial of Buddhist Women’s Monasticism in Thailand’, PhD thesis, Australian National University, October 2006, p.77.

10 Chamsanit, ‘Reconnecting the Lost Lineage’, p.78. See note 9.

11 Bhikkhuni Dhammananda, The Bhikkhuni Lineage, p.19.

Excerpt from This Fresh Existence: Heart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhammananda. Copyright © 2024 by Cindy Rasicot. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

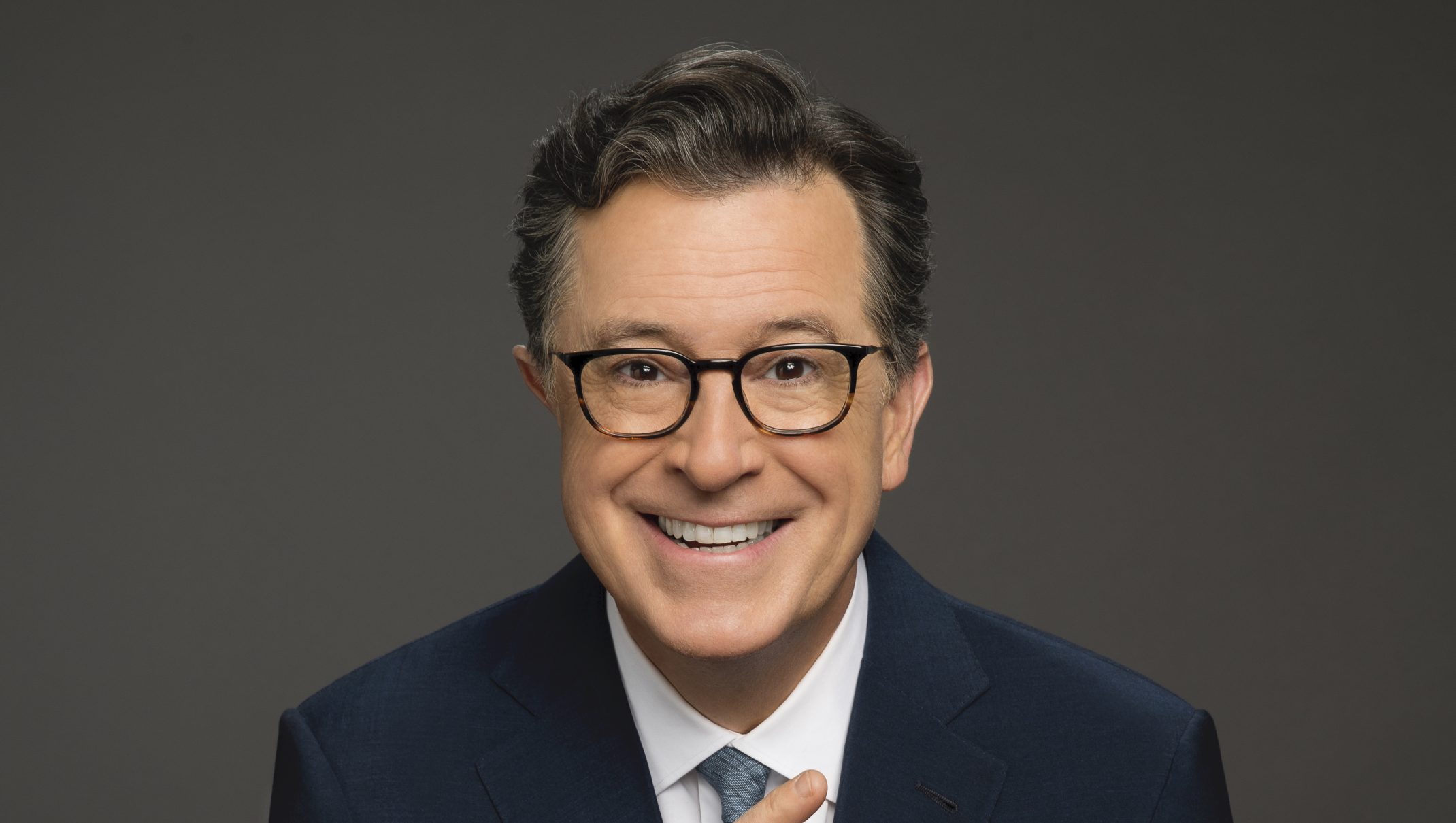

Author Cindy Rasicot.

Author Cindy Rasicot.About the Author:

Cindy Rasicot is a retired psychotherapist and author of This Fresh Existence: Heart Teachings from Bhikkhuni Dhammananda. In 2005 she travelled to Thailand with her family where she met Bhikkhuni Dhammananda — an encounter that changed her life forever. In 2020 she wrote the award-winning memoir Finding Venerable Mother: A Daughter’s Spiritual Quest to Thailand published by She Writes Press. The book is a soulful story of spiritual healing through her loving connection with Bhikkhuni Dhammananda and was a finalist in the international Book awards, The Sarton Awards, and Chanticleer International Book Awards.

Her other writings include an article in Sawasdee Magazine in 2007 and essays featured in two anthologies: Wandering in Paris: Luminaries and Love in the City of Light (Wanderland Writers, 2013) and A Café in Space: The Anaïs Nin Literary Journal, Volume 11 (Sky Blue Press, 2014). Her article, “To Walk Proudly as Women,” was featured in Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Guide in 2021. She previously hosted the YouTube program Casual Buddhism, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcMU-5kE2ux_PbRPwT6HMOg a series of conversations with Venerable Dhammananda about spiritual issues and Buddhist practices. Cindy currently resides in Point Richmond, California, where she writes and enjoys views of the San Francisco Bay. Contact Cindy at cindyrasicot.com.

Troov

Troov