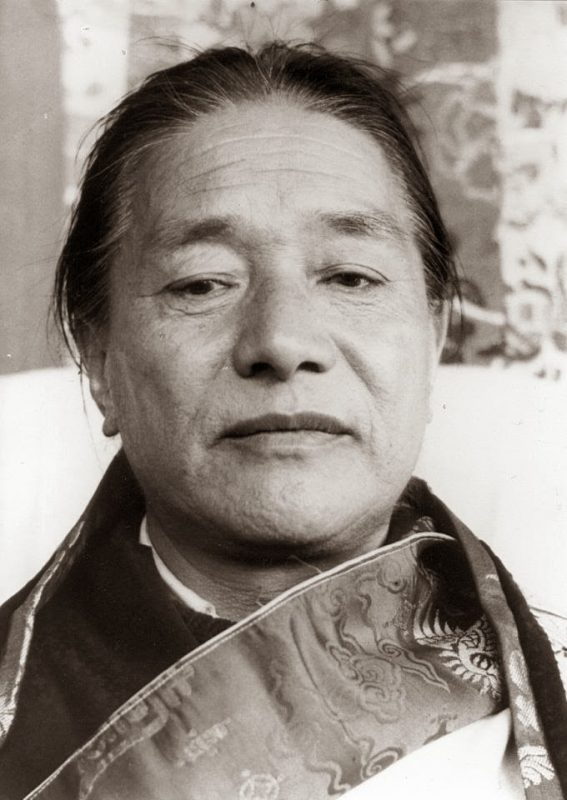

Three Fundamental Teachings of Dudjom Rinpoche

On the anniversary of the prolific teacher and Dzogchen master’s passing, Tricycle takes a look back at three of his essential teachings. The post Three Fundamental Teachings of Dudjom Rinpoche first appeared on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. The post...

Dudjom Jigdral Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche (1904–1987) was a prominent Tibetan lama of the 20th century. Much of his life unfolded in response to the invasion of Tibet by the People’s Liberation Army of China, as well as a burgeoning interest in Buddhism and the mind in the West. As the head of the Nyingma order of Tibetan Buddhism, he played a key role in preserving the tradition and introducing its teachings, such as Dzogchen meditation, to new audiences.

Born in southeastern Tibet, in an area called Pema Köd, Dudjom Rinpoche was recognized as a gifted student from a young age. As a child, he taught the contemplations and ethical training laid out in The Way of the Bodhisattva; later, as a teenager, he delivered an entire cycle of tantric empowerments to a large audience. As he came of age, he continued his studies in the Nyingma monasteries of central Tibet, mastering a diverse curriculum of philosophical literature, poetics, and ritual arts. Celebrated as a master of Dzogchen—the meditative style known as the Great Perfection—Dudjom Rinpoche taught widely in southern Tibet and Bhutan, establishing numerous institutions throughout this area.

Although Dudjom Rinpoche took novice-monk vows for a short period, most of his life was spent as a lay tantric practitioner, or ngakpa. In 1957, he left Tibet with his second wife, Sangyum Rigdzin Wangmo (1925–2014), and their young family. In this period, Dudjom Rinpoche took on a more prominent role as political leader, and in 1960, the Dalai Lama asked him to serve as the representative of the entire Nyingma school for the Tibetan government in exile. He held this newly established position for nearly three decades.

Over the course of his life, Dudjom Rinpoche shared his meditative experience and historical knowledge in numerous books about Buddhism, including an extensive work called The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History. Even before leaving Tibet, Dudjom Rinpoche made great efforts to preserve texts: sponsoring, for instance, the publication of the Adornment for Nagarjuna’s Thought, a controversial philosophical treatise by Gendün Chöpel (1903–1951). After the Chinese army’s invasion of Tibet, and the widespread destruction of monasteries and libraries, he redoubled these efforts, publishing many other rare materials, including a four-volume collection of Sera Khandro’s revelations and a new fifty-eight volume edition of the Oral Teachings of the Nyingma (the Nyingma Kama).

Traveling to the United States for the first time, in 1973, Dudjom Rinpoche visited Berkeley, California, and then continued on to New York. Two of the teachings shared below are from Counsels from My Heart, a collection of oral teachings that contains talks given in the United States. Dudjom Rinpoche served as a role model for an entire generation of Nyingma lamas and students. He also inspired numerous American students from the Beat Generation, including the poet John Giorno. At the end of his life, he established a retreat center in southern France. It was here that he gave his final public teaching and, on January 17, 1987, where he passed away.

Dudjom Rinpoche is remembered among the great Tibetan Buddhist masters of the 20th century, and his teachings continue to find new audiences the world over. These three selections lay out general advice for a student, different ways of understanding the mandala offering practice, and how to relate to thoughts while meditating.

Drawn from Counsels from My Heart, Dudjom Rinpoche gives pithy advice about relating to others and proper conduct in day-to-day life. In Tibet, this type of Buddhist teaching is simply called “advice” or “exhortation,” and it is given to a disciple—usually in person, but sometimes in a written letter—as a way of encouraging them to check their mindset and see if they have developed any negative habits. This genre often addresses many different subjects in quick succession. Here, we see Dudjom Rinpoche highlight topics such as making merit, remembering the kindness of one’s parents, and remaining steady amidst the ups and downs of life. The instructions are meant to be easy to understand, but when we stop and think about them, we realize they are not always so easy to put into practice.

*

“All success, great and small, whether in spiritual or temporal affairs, derives from your stock of merit. So never neglect even the slightest positive deed. Just do it. In the same way, don’t dismiss your little faults as unimportant—just restrain yourself!

Make an effort to accumulate merit: make offerings and give to charity. Strive with a good heart to do everything that benefits others. Follow in the footsteps of the wise and carefully examine everything you do. Do not be the slave of unexamined fashions. Be sparing with your words. Be thoughtful and examine situations carefully. For the roots of discrimination must be nourished: the desire to do all that should be done and to abandon all that should be abandoned. Do not criticize the wise or be sarcastic about them. Rid yourself completely of every feeling of jealous rivalry. Do not despise the ignorant, turning away from them with haughty arrogance. Give up your pride. Give up your self-importance. All this is essential.

Understand that you owe your life to the kindness of your parents, therefore fulfill their wishes. Show courtesy and consideration to all who depend on you. Instill in them a sense of goodness, and instruct them to practice virtue and avoid evil. Be patient with their little shortcomings and restrain your bad temper—remember that the tiniest thing can ruin a good situation.

As for yourself, be constant amid the ebb and flow of happiness and suffering. Be friendly and even with others. Unguarded, intemperate chatter will put you in their power; excessive silence may leave them unclear as to what you mean. Keep a middle course: Don’t swagger with self-confidence, but don’t be a doormat either. Do not be depressed by misfortune and the failure to get what you want, instead be careful to see where your real profit and loss lie.”

In this passage, drawn from his explanation of the preliminary practices called A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom, Dudjom Rinpoche provides instructions on the mandala offering practice. In this ritual, the practitioner places piles of rice and jewels on a golden plate over and over again while uttering an offering prayer. The arrangement of rice and jewels is imagined as a vast mandala—with Mount Meru, the center point of the Buddhist cosmos, surrounded by various continents, and the sun and moon—filled with everything that is precious in the universe. As Dudjom Rinpoche explains in this commentary, the outer mandala is a symbolic way of making a limitless offering to the three jewels. Inwardly, one offers one’s body. And, as we see, there is also a secret aspect of the mandala offering practice, in which the radiant qualities of the mind itself are imaginatively offered.

*

“In general, there is an infinite variety of ways to accumulate merit, and they are all included in the practice of generosity and the other transcendent perfections. However, the offering of the mandala, which is easy to perform and very effective, is the best of all offerings.

From the point of view of actually making the offering, a cloud of offerings like this constitutes the accumulation of merit, while from the point of view of its being backed by wisdom free from concepts, it constitutes the accumulation of wisdom. Even if we make a materially small mandala offering, our special visualization and attitude serve as skillful methods to increase it, and we will therefore gain infinite merit.

On the secret level, imagine the ground consciousness, which is the cause of samsara and nirvana, as the golden ground. Sprinkle it with the scented water of compassion inseparable from bodhicitta. Offer your own naturally arisen, radiant awareness, the precious bodhicitta, represented by Mount Meru; and arising from it, the four boundless attitudes, the four joys, the four wisdoms, and so on represented by the four continents and subcontinents; and means and wisdom united, represented by the sun and moon. In short, offer this spontaneously accomplished mandala of the absolute expanse, which is naturally pure from the very beginning, like an extremely clear mirror, and reflected on its surface, great clouds of offerings filling the very ends of space, appearing as the display, unobstructed in any way, of awareness, the spontaneous primal wisdom, unchanging great bliss. Offer it all.”

In this passage, which is also drawn from Counsels from My Heart, Dudjom Rinpoche gives advice about meditation practice, and how to relate to thoughts. The main point is that thoughts are not an obstacle to meditation; it is OK if there is no thought, and if you do have thoughts, you do not need to try to push them away. Recognizing obvious thoughts and feelings is easy, but subtle thoughts are trickier to notice! Dudjom Rinpoche emphasizes the value of cultivating a relaxed awareness that is divested of all distraction and clinging—an essential element of meditation practice in his tradition.

*

“Settle in a balanced, meditative state. Once you are settled, however, you will not stay long in this empty, clear state of awareness. Your mind will start to move and become agitated. It will fidget and run here, there, and everywhere, like a monkey. What you are experiencing at this point is not the nature of the mind but only thoughts. If you stick with them and follow them, you will find yourself recalling all sorts of things, thinking about all sorts of needs, planning all sorts of activities.

What if you are able to break out of your chain of thoughts? What is awareness like? It is empty, limpid, stunning, light, free, joyful! It is not something bounded or demarcated by its own set of attributes. There is nothing in the whole of samsara and nirvana that it does not embrace. From time without beginning, it is within us, inborn. We have never been without it, yet it is wholly outside the range of action, effort, and imagination.

Just like the waves that rise up out of the sea and sink back into it, all thoughts that appear sink back into awareness. Be certain of their dissolution, and as a result you will find yourself in a state utterly devoid of both meditator and something meditated upon—completely beyond the meditating mind.

“Oh, in that case,” you might think, “there’s no need for meditation.” Well, I can assure you that there is a need!

When thoughts come while you are meditating, let them come; there’s no need to regard them as your enemies. When they arise, relax in their arising. On the other hand, if they don’t arise, don’t be nervously wondering whether or not they will. Just rest in their absence. If big, well-defined thoughts suddenly appear during your meditation, it is easy to recognize them. But when slight, subtle movements occur, it is hard to realize that they are there until much later. This is what we call namtok wogyu, the undercurrent of mental wandering. This is the thief of your meditation, so it is important for you to keep a close watch.

If you meditate with a strong, joyful endeavor, signs will appear showing that you have become used to staying in your nature. The fierce, tight clinging that you have to dualistically experienced phenomena will gradually loosen up, and your obsession with happiness and suffering, hopes and fears, and so on, will slowly weaken.”

♦

Excerpts from Counsels from My Heart and A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom © Padmakara Translation Group. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications.

Kass

Kass