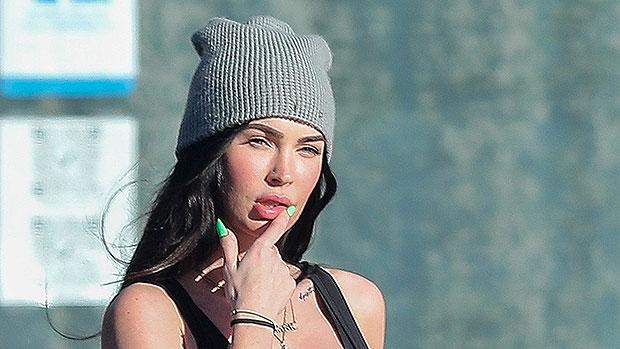

TIFF 2022 Women Directors: Meet Maggie Levin and Vanessa Winter – “V/H/S/99”

Maggie Levin is a filmmaker with rock ‘n’ roll roots. She served as second unit director and credit designer for Universal’s “The Black Phone,” in theaters now. Currently, Levin is adapting the Scholastic novel “Caster” for Paramount Pictures. Her...

Maggie Levin is a filmmaker with rock ‘n’ roll roots. She served as second unit director and credit designer for Universal’s “The Black Phone,” in theaters now. Currently, Levin is adapting the Scholastic novel “Caster” for Paramount Pictures. Her other credits include “Into the Dark: My Valentine,” “MISS 2059,” and music videos for artists such as Big Data and Fast Friends. She won Best Director at Austin Indie Fest for the short film “Heel.”

Vanessa Winter is a writer-director best known for the critically acclaimed SXSW Midnighter film “Deadstream,” a horror comedy she co-wrote and directed with her husband, Joseph Winter, coming to Shudder in October.

“V/H/S/99” is screening at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, which is running from September 8-18. The film is co-directed by Johannes Roberts, Tyler MacIntyre, Flying Lotus, and Joseph Winter.

W&H: Describe the film for us in your own words.

ML: “V/H/S/99” is an utterly gonzo pop-punk collage, taking the format of this legendary cult hit franchise into the depths of hell – if hell were a house party hosted by the demons who tortured you in high school. Without spoiling anything, I think I can say that my segment deals with the hubris of late ’90s white American adolescence, bad pranks, and riot grrrls.

VW: Two guys accidentally get cast into hell after a botched demonic ritual, get saved by a woman literally rotting in hell, and confront some baggage in their friendship in the process.

W&H: What drew you to this story?

ML: The “V/H/S” series presents filmmakers with an incredible, almost unheard-of creative opportunity: to take found footage horror to the absolute hilt of your own imagination. My personal goal with the segment was to make a killer turn-of-the-millennium campfire story that authentically reflected some of my real-life childhood experiences and took bold, boundary-pushing swings for the genre.

VW: I’ve been trying to force Y2K into a script for a long time, so when the producers mentioned that all the segments take place in ‘99, I knew that mine had to be the Y2K segment! I’m also drawn to women characters that are “repulsive,” either physically or mentally, since those kinds of characters have traditionally been male. So, once we decided that our “rotting soul” character would be a woman, I got pretty stoked about her role in the script.

W&H: What do you want people to think about after they watch the film?

ML: Certain kinds of horror leave you feeling grim and anxious, but I believe this movie is designed to do the opposite. I hope the audience leaves “V/H/S/99” feeling cathartically shook up – and strange as it may sound, delighted. Every segment is exhilaratingly giddy in its scare quality. Like a great rollercoaster experience, I hope you walk out feeling wildly alive — and maybe a touch relieved we’ve put the ’90s far in our rearview.

VW: My first objective was for people to have fun with the characters and celebrate the art of practical creature FX [effects]. I also thought a lot about our desire as human beings to be categorized as “good people.” The question of whether or not wanting to be a “good person” automatically negates the idea is a loop that I got stuck in a lot.

W&H: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

ML: It was very important to me that the segment be as era-authentic as possible – from the posters on Rachel’s bedroom wall, to the cameras we filmed on, to every last glitch effect seen in the final film. I was lucky to have a team as excited about these details as I was – but to work in vintage mediums means working with their flaws. Getting everything compatible with modern formats was no small feat.

Tracing the rights-holders to obscure ’90s video clips, getting a handheld monitor to run off a VX1000 camcorder — these sorts of challenges came up at every turn. My amazing editor, Andy Holton, “hand made” nearly every glitch you see onscreen, by intentionally messing with the footage on a VHS camera, and recording those interferences digitally. It certainly helped to have allies like Andy in the trenches with me, tackling every new challenge along the way.

VW: The fast turnaround and the remote locations. They were so far away from anything and navigating the difficult terrain created a lot of restrictions.

W&H: How did you get your film funded? Share some insights into how you got the film made.

VW: When we came on board, the financing for “V/H/S/99” was already in place. In fact, the other segments were already in production in LA. We were basically given a set dollar amount to film our segment separately in Utah. There was a lot of trust from the producers in our team to spend the money where we thought it would go the furthest.

W&H: What inspired you to become a filmmaker?

ML: From an early age, I thought I’d grow up to become a theater director, but films were a constant companion to me. I watched “Se7en” and “Detroit Rock City” on my VHS player so often I’m surprised I didn’t wreck the tapes. I’d study theater at conservatory all day, then go home and watch “Lost Boys” for the 80th time in a row. It somehow didn’t occur to me that someone like me, i.e. a girl, could be a filmmaker – for years, I was own sexist gatekeeper! I moved out to LA to direct a play, and upon sticking around thought I’d take a swing at filmmaking. I was shocked to discover not only did I love doing it – it felt like what I was meant to be doing all along. A natural, creative homecoming. And I’ve been at it ever since.

VW: I remember the exact moment. I was completely new to film and was doing the production design for a student project that was going way over schedule, which resulted in me taking on additional roles. I was wearing and operating all the sound gear that I barely knew how to use while holding a bunch of expensive lenses on my lap for the DP, who was sitting next to me holding a giant 16mm camera. All of this was happening in the back of a barely functional ’70s car that was spinning donuts with the actor on the windshield. I was terrified and everything was going horribly but for some reason that’s when I knew I was “all in” with the strange art of filmmaking. Writing, directing, producing, pretending I knew how to record sound. All of it. For the rest of my life.

W&H: What’s the best and worst advice you’ve received?

ML: Best advice: “Write your own meal ticket.”

Worst advice: Any variation of “wait your turn.” If you’re a woman or minority in this business, you have to go take your turn, or no one will know you’re there.

VW: The worst advice I received was more like strong messaging picked up in film school that there wasn’t enough room for everyone to be successful. Not only is that silly, but rooting for and supporting each other is the only way to get projects made.

One helpful piece of advice that I’ve gotten is to define your own success. Of course you want other people to like your films, but having some personal goals I can attain within each phase of a project has helped me find satisfaction that isn’t dependent on other people’s reactions.

W&H: What advice do you have for other women directors?

ML: It’s okay to let the world know about your strengths and skills. It’s okay to broadcast who you are, and what you have to offer as an artist. All of our social programming tells us to keep quiet, be modest, “wait your turn.” But when you’re starting out, no one is gonna hype you up but you. So don’t wait. Tell them all what you’re on this planet to do.

VW: The other day I was talking to a fellow crew member and realized that I have never been on a set while another woman was directing. I’m friends with other female directors and I’ve crewed a lot of sets, but I’ve never seen another woman direct. It made me think about the first time I was ever hired by a female producer or worked with a female DP, and how it was inspiring for me to see other women working with their own style, in their own way, in a predominantly male environment. I wish I would have sought out more of those experiences when I was starting out, so that would be my advice to someone new.

W&H: Name your favorite woman-directed film and why.

ML: Is there any movie that is objectively better than Amy Heckerling’s “Clueless”? I’d watch “Clueless” any hour of any day — doesn’t matter what mood I’m in, “Clueless” is gonna be the cure for what ails me.

VW: There are a lot! Mary Lambert’s “Pet Sematary” and Penelope Spheeris’ “Wayne’s World” come to mind because they’re both enduring classics by women paving the way for other female directors in genre. They’re also both movies I loved before finding out they were directed by women, and I remember how excited I felt learning that they were helmed by women.

W&H: What, if any, responsibilities do you think storytellers have to confront the tumult in the world, from the pandemic to the loss of abortion rights and systemic violence?

ML: It may not be our “responsibility” to confront the tumult in the world, per se – but I think it’s quite rare to meet a filmmaker who isn’t interested in sharing their experience of these things with others. I think when we’re called to this profession, we are innately called upon to engage with and reflect upon the human experience in a profound and impactful way. And when you have the opportunity to show an important truth onscreen, I think you gotta take that and run with it.

VW: When I was growing up, the first really nuanced conversation I heard about abortion was people I didn’t know discussing the film “Cider House Rules.” I hadn’t even seen the movie, but just hearing people talk about it was an education for me. I think that one of the powers of art is its ability to start conversation and change the way you look at the world.

W&H: The film industry has a long history of underrepresenting people of color onscreen and behind the scenes and reinforcing — and creating — negative stereotypes. What actions do you think need to be taken to make Hollywood and/or the doc world more inclusive?

ML: In 2022, there’s simply no excuse or reasoning for onscreen representation to lack diversity. In my experience, writers, directors, producers, casting directors, and executives are conscientiously pushing for in-front-of-the-camera talent to reflect the look of our world.

But when it comes to behind-the-scenes, those with power need to relentlessly and aggressively vouch for those without it. It’s very difficult to get studios and production entities to take a “risk” on an “unknown” – i.e. someone who hasn’t been given their fair shot at the gigs that would make them qualified for other, bigger gigs. I needed powerful people to vouch for me for my career to begin in earnest. I look forward to doing the same for other women and minorities, and I believe if we all do this, it’s possible to make our industry far more inclusive.

VW: I think one thing that everyone can do is to seek out and support content from different voices. Without making the effort, it’s easy to keep watching and perpetuating the ideas that are already grandfathered into the film industry.

UsenB

UsenB