Twitter’s CEO is now Twitter’s main character

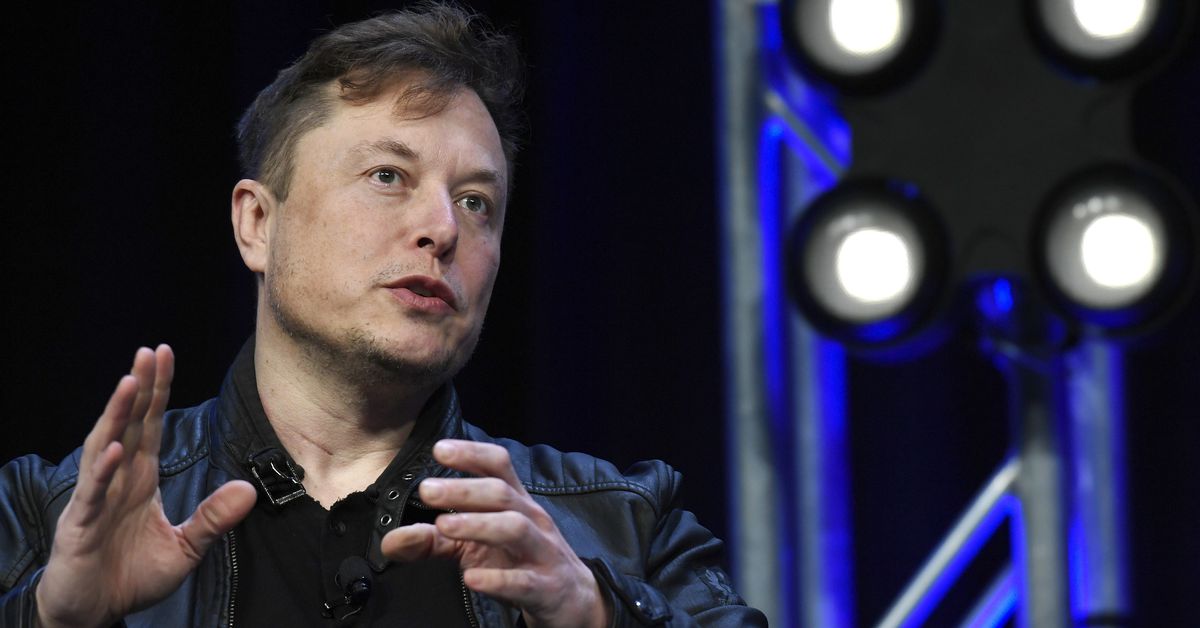

Elon Musk speaks at the Satellite Conference and Exhibition in Washington, DC, in 2020. | Susan Walsh/APElon Musk’s disaster month at Twitter has come to a close. Let’s discuss. About a week and a half after buying Twitter and...

About a week and a half after buying Twitter and assuming the role of CEO, Elon Musk rolled out a new service letting users pay $8 a month for a verification check mark without actually verifying their identity.

Musk had portrayed the old verification model as a system of “lords & peasants,” tweeting, “Power to the people!” New check-mark-wielding accounts wasted no time in impersonating brands, such as Musk’s own car company, Tesla, and pharmaceuticals company Eli Lilly, even announcing that the insulin manufacturer would now offer insulin for free, sending the actual Eli Lilly’s stock prices into a free fall. A fake LeBron James requested a trade to another NBA team. An account impersonating former president George W. Bush tweeted, “I miss killing Iraqis.”

Within days of its launch, the service was paused. Musk said it would be relaunched when there was “high confidence of stopping impersonation.”

The much-mocked launch of paid blue checks is just one example of the eyebrow-raising decisions Musk has made since his $44 billion purchase of the social network one month ago. A short list of ideas he’s thrown at the wall in the weeks since: bringing back Vine, paid video content, paid direct messages to celebrities, a Twitter payments platform (which could include a high-yield money market account) — even putting the entire site behind a paywall. In his first month, Musk also reinstated the Twitter account of former President Donald Trump, who was permanently suspended in January 2021 for inciting violence in light of the January 6 Capitol attack.

As Musk’s first month as Twitter’s CEO comes to a close, his run can only be described as head-spinning. Musk’s strategy so far, however, echoes a Silicon Valley ethos attributed to Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg: “Move fast and break things,” says Peter Harms, a professor of management at the University of Alabama who has researched authoritarian leadership styles.

Fears that Twitter might actually break have reached a new pitch. Under Musk’s leadership, Twitter laid off about half of its workforce in the first week of November; it also laid off 4,400 out of 5,500 contract workers. Some 1,200 additional employees resigned after Musk set a deadline by which they’d have to decide to stay or leave, and #RIPTwitter began trending on the site. Meanwhile, advertisers have disappeared from the site, taking millions in revenue with them: According to a new report by Media Matters for America, half of Twitter’s top 100 advertisers, from Coca-Cola to American Express to Chevrolet — who spent a collective $2 billion on Twitter ads since 2020 — seem to have stopped advertising on the site.

The chaotic implementation of new features and the company’s cold-blooded treatment of employees have attracted a torrent of criticism from Twitter users, former and current Twitter employees, journalists, and others. Twitter is a very public stage, and Musk as its CEO is airing out his every thought — no matter how inane or crude — for the public to see.

Musk is no novice at running companies. But the confusing vision he has presented for Twitter in his first month on the job has made it clear that running a social network is, in fact, hard, and that selling this town square as a monetizable product is proving to be a far more confounding prospect for Musk than even selling EVs.

It’s a job that requires managing the expectations and desires of a vast, diverse swath of people who often feel a sense of ownership over the social network, and perhaps rightfully so; they’re the ones bringing value to the platform with every tweet. After Musk announced the possibility of introducing a monthly fee to keep using Twitter as a verified user, the response was swift: “Fuck that, they should pay me,” author Stephen King tweeted.

It stands to reason that Twitter’s CEO should understand the relationship between the platform and its users. Musk, however, has sent conflicting messages about how he sees Twitter: According to a recent missive from Musk, Twitter isn’t a democracy-promoting town square, as he’s long suggested it is, but “at its heart, Twitter is a software and servers company,” one that needs a “technologist” as its CEO.

“He’s been very successful at a lot of things,” said Harms. “But we know from other stories that he’s also kind of volatile and impulsive. He sometimes fires people on a whim. And quite often, he makes mistakes.”

On Musk’s “hardcore” leadership

Stories of Musk as the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX often paint him as a demanding taskmaster who has a hand in almost every decision at his companies. Musk biographer Ashlee Vance reported early on in Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future about one particular incident when a number of employees were present at Tesla headquarters on a Saturday. “Musk saw the situation in a different light,” Vance wrote, “complaining that fewer and fewer people had been working weekends of late. ‘We’ve grown fucking soft,’ Musk replied. ‘I was just going to send out an email. We’re fucking soft.’”

Still, the environment-saving, Mars-exploring grandness of the Tesla and SpaceX missions held considerable sway over workers. Musk’s cult of personality as a real-life Tony Stark built hype and brand loyalty, and this personal brand helped catapult his businesses to incredible success: Tesla is one of the most valuable companies in the world, and SpaceX is now NASA’s second biggest contractor.

“When Musk sets unrealistic goals, verbally abuses employees, and works them to the bone, it’s understood to be — on some level — part of the Mars agenda,” Vance reported. “Some employees love him for this. Others loathe him but remain oddly loyal out of respect for his drive and mission.”

Twitter, however, is not Tesla or SpaceX. Treating it only as a software and servers company misses its utility as a social space. It’s like describing a restaurant as an emporium of tables and chairs.

“It is, for better and worse, the town square, and it also sometimes brings out the worst in people in that town square. And I think [Musk] drastically underestimated how difficult of a challenge that is,” said Nick Bilton, author of Hatching Twitter: A True Story of Money, Power, Friendship, and Betrayal.

Bilton, who reports on tech and business for Vanity Fair, told Vox that former Twitter CEOs have also had their own takes on how to run the social network. “Evan Williams’s approach to running Twitter was a very product-oriented approach and less of a business approach. Dick Costolo’s version of Twitter was to try to fix all of the technical problems and make the company go public, which he did,” Bilton said. “Jack [Dorsey]’s was a very hands-off one — he felt like someone who just didn’t want to touch it, or do anything that could break it.”

The ideal Twitter CEO probably doesn’t need to be a “product genius” or a “business genius,” Bilton said, but instead — believe it or not — someone like Jeff Bezos. “People can love or hate Amazon — but where [Bezos] deserves credit is he ran a company where he delegated,” he said. “His job was to kind of be a statesman for Amazon. It was almost like a godfather, if you will. I feel like Twitter needs the same thing. It needs a variety of viewpoints and people and expertise, and I feel like the CEO should not be the person dictating that.” (Musk said recently that he doesn’t intend to remain Twitter’s CEO, but it’s unclear who he would hand the reins to or when he would do so.)

Musk’s strategy, as Bilton describes it, appears to be to “slam on the gas pedal” while hoping he doesn’t hit anything. And while others might agree that Twitter could be improved and that the site hasn’t innovated enough since it first launched in 2006, Musk’s breakneck pace of transforming Twitter is on a collision course with his highly visible persona — his non-stop tweeting, and more specifically, tweeting about his personal politics.

Is Musk tweeting too much?

When Musk first reached a deal to buy Twitter in April, he said the site’s noble mission was to be a politically neutral, free speech “town square.” Musk himself has long been a prolific tweeter, telling interviewer Chris Anderson at the 2022 TED Conference that he tweets “more or less stream-of-consciousness,” and telling Twitter employees in a meeting over the summer that he preferred tweeting to issuing press releases.

Now he’s the CEO of a social media platform tweeting encouragement to his 115 million followers to vote for Republican candidates a day before the midterm elections, and that the balance of power is stacked against conservatives, and promoting a right-wing conspiracy theory about the recent attack on Paul Pelosi. An MIT study estimated that more than 875,000 users may have deactivated their accounts between October 27 and November 1 — the first few days of Musk’s tenure. Twitter estimates that it has around 237 million monetizable daily active users.

Musk wants to convince people of his vision of a politically neutral Twitter — yet also wants to remain highly opinionated on a vast range of political issues. “It threatens Twitter’s ability to be the number one source for news, which is what [Musk] is trying to do with his blue badge tactic,” said Bilton. “The things he wants to do don’t necessarily correlate with the things he thinks he wants to tweet.”

Management experts have varying views on how vocal corporate leaders should be about their politics, but few would argue for the degree of soapboxing Musk has done. “My personal take is that it’s a bad idea,” said Harms. “[Twitter] essentially trades in people sharing their opinions and freedom of speech — so it becomes kind of sensitive.”

Being Twitter CEO is by nature more politically fraught than Musk’s prior ventures. The company is a major media platform that regularly addresses a broader set of consumers than electric car and space enthusiasts (even with its declining user base); it’s public-facing in a way that Musk’s previous executive roles haven’t been.

The platform is at the center of an ideological fight, and Musk has been pretty clear about taking sides. Beyond criticisms of the Democratic Party, including implying that Democrats may have laundered money for disgraced crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried, Musk has also been replying to and soliciting evidence from users claiming Twitter unfairly suspended several Brazilian right-wing politicians accusing the opposition of committing fraud in its recent elections. Musk’s foreign business ties have even gotten the attention of President Joe Biden, who recently said that the relationships Musk’s other companies had with other countries was worthy of scrutiny.

Though past Twitter CEOs were much more restrained about their own politics, they have also faced plenty of criticism and backlash from various factions for their handling of content moderation on the site. “All 765 CEOs that have run the company have all had a very difficult time dealing with the problems around politics and hate speech,” Bilton said, cracking a joke about the company’s frequent leadership changes. “Donald Trump was president for three-and-a-half years before they finally started fact-checking his tweets.”

In 2018, then-CEO Jack Dorsey testified at a House hearing on Twitter transparency and accountability, addressing Republican politicians’ concerns of partisan bias in Twitter’s algorithm as well as what the site was doing to combat disinformation. On the day of his testimony, Dorsey tweeted, “I want to start by making something clear: we don’t consider political viewpoints, perspectives, or party affiliation in any of our policies or enforcement decisions.” He continued in another tweet, “Twitter cannot rightly serve as a public square if it’s constructed around the personal opinions of its makers.” Under Dorsey’s reign, Twitter banned political advertising.

Twitter’s most recent ex-CEO, Parag Agrawal — who was fired by Musk the day he took ownership of Twitter — was arguably even more reticent to wade into ideological feuds. “You won’t see tweets from me on the ‘topic of the day’ or the loudest sound bite, but rather on the ongoing, continuous, and challenging work our teams are doing to improve the public conversation on Twitter,” Agrawal tweeted a few months ago, making rare public comments after Musk claimed that the deal he’d signed to buy Twitter was “temporarily on hold.”

While Musk’s outspokenness could sometimes be a boon for driving enthusiasm for his other companies, winning him loyal fans who saw his work as a testament to the power of human innovation, for a site long embattled by political fights, it’s a big risk. The conflict between Musk’s celebrity and his role as the top executive of multiple companies has been long simmering, but at Twitter it appears to be at the boiling point.

Bilton believes that it’s “one thousand percent” hurting Musk’s ability to run Twitter. “His biggest problem right now is not necessarily what he’s doing to the company,” he told Vox. “His personal biggest problem is his Twitter account.”

Musk’s challenge is employee trust

Musk grew his previous companies either from their inception or, in the case of Tesla, from its early days; he wielded a lot more control over what kind of employees he would hire and what kind of culture he would build over the years. “He was able to push his personality stamp on them right from the beginning,” Harms said.

Twitter has a longstanding work culture of its own. For one, Twitter employees tend to be liberal. Musk now votes for Republicans. “So you’ve got a hostile workforce, ideologically — you’ve got one that’s a little incompatible in terms of his values,” Harms said.

But Harms said he believes that the single biggest challenge Musk will face at Twitter is gaining employees’ trust. “Right now, that’s absolutely not there,” he said.

In the meantime, Musk has brought Tesla engineers to work at Twitter. The billionaire is dealing with an increasingly resentful staff, reflected in a month of mass resignations.

The manner in which many other employees were laid off has been widely condemned by human resources professionals. The email notifying staff that layoffs were imminent wasn’t personally signed by Musk. While the layoffs were already underway, Musk tweeted, “Regarding Twitter’s reduction in force, unfortunately there is no choice when the company is losing over $4M/day. Everyone exited was offered 3 months of severance, which is 50% more than legally required.” The cuts happened November 4; the first staff-wide email Musk sent with his name attached came on November 10.

By comparison, Meta laid off 13 percent of its workforce in November, and CEO Mark Zuckerberg sent employees a lengthy letter expressing his regret and attempting to explain the state of the company. This isn’t especially noteworthy in the big picture of corporate layoffs; one could argue that it’s the bare minimum. But the timing has provided an unlikely contrast to Musk’s leadership. “He was transparent and basically said, ‘Listen, I miscalculated,’” said Matthew Kerzner, the managing director at management consulting firm Eisner Advisory Group. “He laid the case of why he was doing what he was doing.”

At Twitter, “they sent everyone home one day and they said, ‘you’ll get an email tomorrow morning, and you might be fired, or you might not,’” said Harms, the management professor. “That’s really stressful, and even the survivors are going to be incredibly stressed out by that experience, because you now know you’re in an environment where no one is safe at all. It makes it very hard to do things.”

Employees at Tesla and SpaceX have faced mass layoffs and impetuous firings too. Musk has a history of firing employees who criticize or disagree with him, according to the biographies written about him. In June, a leaked email showed that Musk planned to lay off about 10 percent of Tesla’s 100,000-strong workforce (Musk later said the true number would be closer to 3.5 percent). Two laid-off employees sued Tesla alleging that it violated federal labor laws by not providing enough notice. The case has been moved to out-of-court arbitration between Tesla and the ex-employees. Nine SpaceX employees were fired this past summer for penning a letter to company executives voicing concerns about Musk’s leadership and recent public behavior, including his downplaying of a sexual misconduct allegation.

Unlike with Musk’s other companies, no ambitious, specifically Musk-branded Twitter mission exists to draw awe or even begrudging respect for his leadership. Combine that with the fact that Twitter employees are often avid users of the platform, and the result is that the kind of workplace toxicity that used to play out behind the scenes at Tesla and SpaceX is suddenly out in the open for all to see when it comes to Twitter.

Twitter’s CEO has eclipsed Twitter itself

Musk is now one of the most hyper-visible corporate leaders in the world. Recent data from Morning Consult shows that almost all US adults — 94 percent of them — now know who Musk is, compared to 75 percent in early 2021.

But name recognition isn’t always good — just ask Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg. He’s America’s most recognizable CEO, according to the Morning Consult study — and his favorability was also the lowest of all the CEOs included in the report, while Meta had the lowest favorability of all analyzed companies. Musk’s outspokenness has apparently damaged his reputation: His net favorability has plummeted in the past year, from +22 percentage points to +9.

Jordan Marlatt, a tech analyst at Morning Consult, credits the public’s negative impression of Zuckerberg largely to the 2018 Cambridge Analytica user data scandal. “Facebook never quite recovered from that, and neither did Zuckerberg, because their brands are so intertwined,” he told Vox. Musk has been the subject of condemnation for his treatment of Twitter employees, but his high-profile Twitter persona is sowing more anger and chaos during a crucial transition period for the social media company. He’s now the face of a platform that journalists, pundits, activists, and trolls routinely use to criticize public figures.

People do want corporate leaders to take a public stance on issues that are politically and socially important to them, Marlatt said, but “that doesn’t necessarily mean just any issue.”

He noted that there’s specifically an increased demand for CEOs to speak up on employee well-being.

The Morning Consult report found that the top expectations most people surveyed had of CEOs was that they respect customers’ privacy, lead with honesty and integrity, and have a positive impact on employees. Least important was having a “highly visible public persona.”

“It’s a very delicate balance for corporate leaders,” said Marlatt. “How do they come across as taking stands on issues that are important to their consumers without alienating too many of them at the same time — or making it all about themselves?”

It’s unclear when exactly Musk will appoint someone else as CEO, removing himself as the public face of the company. “I see him being very visible for the first six months to a year until things settle down,” said Kerzner.

Harms agrees, saying that what Musk likely needs is an “emotionally stable and boring number two, who can kind of smooth things out — you’ll find that with a lot of difficult leaders.”

“He has so many challenges, quite frankly,” said Bilton. “But I think his biggest challenge right now is himself.”

Help keep articles like this free

Understanding America’s political sphere can be overwhelming. That’s where Vox comes in. We aim to give research-driven, smart, and accessible information to everyone who wants it.

Reader gifts support this mission by helping to keep our work free — whether we’re adding nuanced context to unexpected events or explaining how our democracy got to this point. While we’re committed to keeping Vox free, our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism does take a lot of resources. Advertising alone isn’t enough to support it. Help keep work like this free for all by making a gift to Vox today.

Lynk

Lynk