Two years into the coronavirus pandemic, Fauci hopes the world will not forget lessons from a 'catastrophic experience'

Two years after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic, public health experts warn not to become complacent.

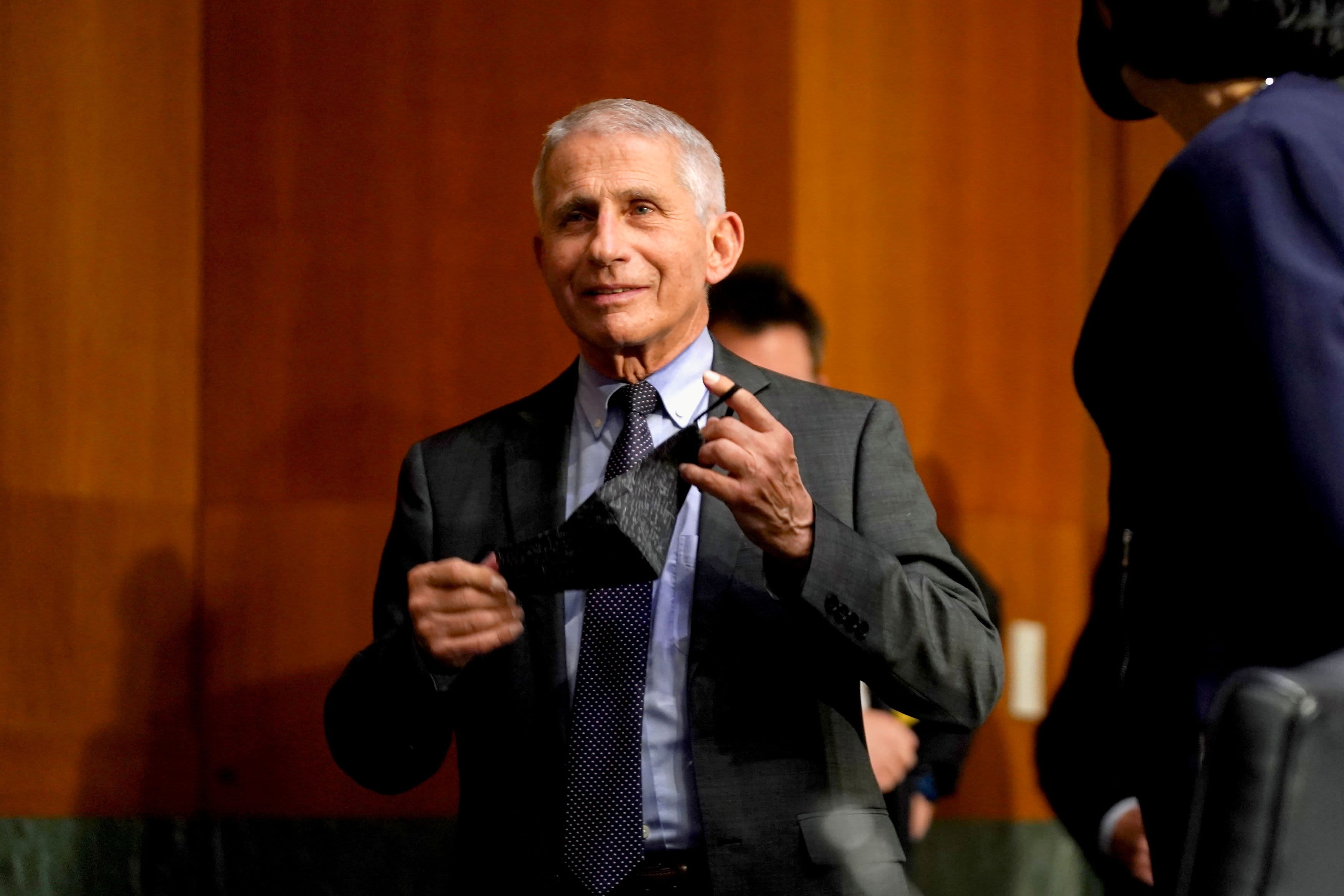

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, arrives for a Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing to discuss the on-going federal response to COVID-19, at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., May 11, 2021.

Greg Nash | Pool | Reuters

As the two-year anniversary of the coronavirus pandemic declaration approached last week, White House chief medical advisor Dr. Anthony Fauci was in no mood to predict the future.

"The answer is: We don't know. I mean, that's it," Fauci told CNBC when asked what may come next for Covid-19 vaccinations. Given the durability of protection from the shots, "it is likely that we're not done with this when it comes to vaccines," he said.

Two years into a pandemic that has killed more than 6 million people globally, and nearly 1 million in the U.S., leaders in public health, academia and industry expressed ambivalence as much of the rest of the world — or at least the U.S. — appears to be trying to move on. Despite progress in beating back the highly transmissible omicron variant, they stressed that globe leaders cannot let their vigilance lapse.

"Everybody wants to return to normal, everybody wants to put the virus behind us in the rearview mirror, which is, I think, what we should aspire to," said Fauci, who is also the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

While he acknowledged "we are going in the right direction" as cases, hospitalizations and deaths decline after the omicron surge, he pointed out "we have gone in the right direction in four other variants" before the pandemic took a devastating turn.

As states and cities scrap many of their pandemic restrictions, dire public health conditions linger. The U.S. is still recording more than 1,200 deaths per day from the coronavirus. Hospitalizations have recently ticked higher in the United Kingdom, a previous harbinger for what may hit the U.S.

As the world on Friday marked two years since the World Health Organization first called the coronavirus a pandemic, the agency's scientists argued last week that the more important anniversary came more than a month earlier. In January 2020, the WHO warned that the disease that would come to be known as Covid-19 was a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Everybody wants to return to normal, everybody wants to put the virus behind us in the rearview mirror, which is, I think, what we should aspire to... We have been going in the right direction; however, we have gone in the right direction in four other variants.

Dr. Anthony Fauci

Director, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

"What we were saying in January was: 'It's coming, it's real, get ready,'" said Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of WHO's health emergencies program, in a briefing Thursday. "What I was most stunned by was the lack of response, was the lack of urgency, in relation to WHO's highest level of alert."

That lower level of urgency appears to have settled in once again. Congress last week sidelined new funding for the Covid response despite White House press secretary Jen Psaki's warning that the U.S. needs funds to secure critical supplies.

She said that without more aid, the U.S. risks dropping testing capacity within weeks, running out of monoclonal antibody drugs by May — exhausting the only medicine to preventively protect the immunocompromised by July — and going through antiviral pills by September.

"I am concerned," Pfizer Chief Executive Albert Bourla said on CNBC's "Squawk Box" on Friday morning about the lack of new federal funding. He noted that because vaccine boosters and antiviral pills are only cleared through Emergency Use Authorization, the government is the only allowed purchaser.

"So if the government doesn't have money, nobody can get the vaccine," Bourla said.

While concerns about pandemic preparedness have not gone away, neither has work on the vaccines, new medicines and Covid surveillance.

Moderna said last week that it had started a trial of a vaccine against both omicron and the original strain of the virus to help inform public health authorities making decisions about boosters for the fall.

Bourla also said Friday that Pfizer expects to submit data to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration soon for a fourth shot, or a second booster, of its vaccine. He said data shows that while protection against hospitalization and death from the omicron variant is high with three doses, "it doesn't last long — after three or four months, it starts waning."

Dr. Clay Marsh, chancellor and executive dean for health sciences at West Virginia University and the state's Covid czar, agreed that emerging information from Israel and the UK — both of which are administering additional doses to the elderly — supports considering additional boosters in the U.S.

"To me, that's something that the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and the FDA should be leading," Marsh said. "And I don't see it."

Marsh said the state has enough vaccine supply to administer additional boosters, if authorized. He noted that antiviral pills — or at least the most preferred one, Pfizer's Paxlovid — still are not plentiful.

States have received about 689,000 courses of Paxlovid since it started shipping in December, federal data shows, compared with more than 2 million courses of Merck's antiviral pill, molnupiravir. But Merck's drug is typically a last-choice option for prescribers due to lower efficacy and safety concerns for some groups, Marsh said.

He noted that Paxlovid can also be complicated to prescribe because it interacts with some commonly used medications, like statins.

Monoclonal antibody drugs are typically the next choice after Paxlovid, he explained. There are two available as treatments — sotrovimab, from Vir Biotechnology and GlaxoSmithKline, and bebtelovimab, just authorized from Eli Lilly — after omicron rendered earlier antibody drugs such as a Regeneron cocktail ineffective.

In an interview last week, Regeneron's chief scientist said the company is assessing variants to decide on the best new combination of antibodies to bring through clinical testing and the FDA authorization process.

"What we learned is that no single antibody and even the cocktail of antibodies that we employed can withstand all these variants," Regeneron's Dr. George Yancopoulos explained. "So what you have to have is a very large collection of different antibodies, which is what we've been assembling over the years."

He said the company is discussing with the FDA a strategy to have a series of antibody drugs tested in humans for safety and initial data. In the case of a new surge, Regeneron would be able to rapidly choose the right antibodies to put in a new drug.

The timeline for getting that drug to market would depend on whether the agency adopts a more flexible regulatory pathway, similar to what it did for Covid vaccines, he said. It could mean the difference between months and weeks for the availability of a new drug during a surge.

Whether another surge will take place is, of course, an open question. Cases have climbed slightly in Europe, Evercore ISI's Michael Newshel pointed out Thursday in his research note on Covid surveillance. What's more, The U.K.'s rise in hospitalizations has perplexed experts there.

In the U.S., the University of California San Francisco's Dr. Bob Wachter suggested the U.K. data may mean a "need to resume more caution in a month or two."

A Biobot Analytics employee holds a sample of wastewater used for coronavirus surveillance.

Source: Biobot Analytics

If a new surge happens, the first clues may come from wastewater. While the U.S. system for monitoring sewage for upticks in the coronavirus is still piecemeal, in cities where it is employed, it can provide a lead time of as many as a few weeks before cases start to rise, said Dr. Mariana Matus, CEO and co-founder of Biobot Analytics.

The company works with a network of wastewater treatment plants across 37 states, covering about 20 million people. Each week, it tests samples comprising less than a cup of wastewater for their concentration of the coronavirus; one $350 test can represent between 10,000 and 2 million people, Matus said in an interview.

"People who get infected with the disease will start shedding very early on ahead of developing symptoms," she explained. "So they start to produce a signal in the wastewater even before they feel that they should go and get a test. And that's super powerful."

Testing volumes have declined along with the omicron health crisis in the U.S., making this kind of passive surveillance more helpful, especially in large population centers like New York City and Los Angeles, Marsh said.

Though cases are declining, experts stressed it's not time to become complacent about Covid.

"The problem here and throughout the world is that the memory of what happened fades very quickly," Fauci warned. "I would hope that this completely catastrophic experience that we've had over the last two-plus years will make it so that we don't forget, and we do the kind of pandemic preparedness that is absolutely essential."

— CNBC's Nick Wells and Leanne Miller contributed to this report

UsenB

UsenB

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=f776164e2b&c=1)