What does Russia’s invasion of Ukraine mean for Chernobyl?

Servicemen take part in a joint tactical and special exercises of the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ukrainian National Guard and Ministry Emergency in a ghost city of Pripyat, near Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant on February 4, 2022. ...

Conflict between Ukrainian and Russian forces near Chernobyl raised fears that the site of the worst nuclear accident in history might be disturbed. The site still contains radioactive debris, which the world has worked to contain in the 36 years since the disaster.

Russian troops seized the nuclear power plant today, according to scattered reports from officials, including Ukrainian presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak.

“It is impossible to say the Chernobyl nuclear power plant is safe after a totally pointless attack by the Russians ... This is one of the most serious threats in Europe today,” Podolyak said, according to Reuters. The International Atomic Energy Agency, however, said in a statement that the Ukraine regulatory body reported “no casualties nor destruction at the industrial site.”

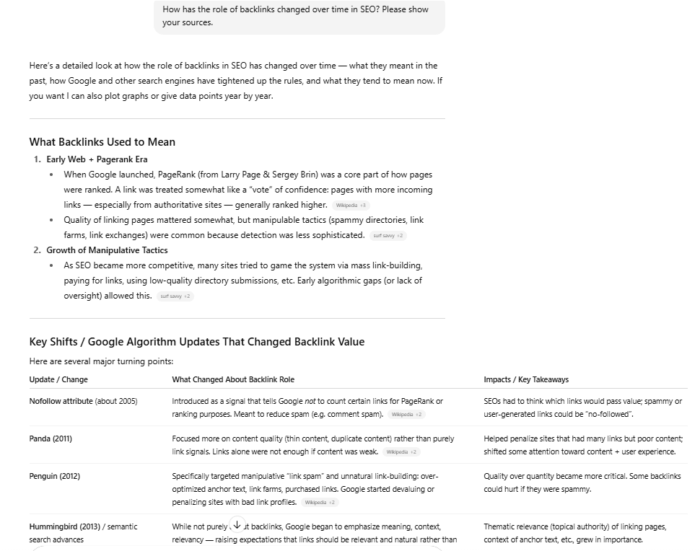

The Verge spoke with experts on nuclear policy and the Chernobyl disaster about what we might be able to expect out of this rapidly changing situation. A worst-case scenario is unlikely, but ongoing conflict in Ukraine makes this already sensitive location even more difficult to manage.

The 200 metric ton elephant in the room is the “highly radioactive material” still held in the remains of the reactor that exploded at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986, according to the trade group World Nuclear Association. That reactor failed catastrophically during a test run — releasing radioactive particles in the ensuing explosion and fire. About 50 people died in the following two decades as a direct result of the incident, according to a 2005 United Nations report, and tens of thousands more people might have been affected by the radiation.

To try to keep radioactive material from spreading, a “sarcophagus” was quickly built afterwards to entomb the reactor’s remains. Nearly a decade later, officials decided to construct a more secure cover for it — a gigantic steel New Safe Confinement Arch that was just completed in 2017 at a cost of $1.7 billion. That structure is also supposed to facilitate cleanup; workers can remotely operate a crane and other equipment inside to dismantle the rest of the the reactor and remove radioactive fuel.

If that structure gets damaged and there are explosions inside it, it could stir up remaining radioactive material that might release radioactive emissions according to James Acton, a physicist and co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. But that would take a a direct hit — either on accident or through a concentrated effort to damage the containment unit which was designed to withstand a tornado.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23269310/1232301312.jpg) A picture taken on April 13, 2021 shows the giant protective dome built over the sarcophagus covering the destroyed fourth reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant ahead of the upcoming 35th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.Photo by SERGEI SUPINSKY/AFP via Getty Images

A picture taken on April 13, 2021 shows the giant protective dome built over the sarcophagus covering the destroyed fourth reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant ahead of the upcoming 35th anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.Photo by SERGEI SUPINSKY/AFP via Getty Images

A bigger concern is spent fuel from three other decommissioned reactors at Chernobyl that continued operating for years after the 1986 disaster, according to Acton and retired nuclear scientist Cheryl Rofer. Used fuel from those reactors is more radioactive than what’s been sequestered inside the giant confinement arch since it’s been more recently removed from the reactors. It was transferred to nearby cooling ponds for interim safekeeping. To date, Acton says, there has never been a serious accident involving spent fuel anywhere. But if something happened to cause the less protected cooling pools to sustain damage and drain out, the remaining fuel could melt and release radioactive gases and particles.

Some of that spent fuel has already been transferred to a newer and more permanent dry storage facility completed in 2020. More of it is supposed to move over in the next several years. Dry storage facilities don’t require water cooling, and steel or cement casks inside house materials that have already had some time to cool off in wet pools.

“Those casks are not designed to withstand attacks, but nonetheless, they are extremely strong and robust,” Acton says. Nevertheless, if they’re broken, they can release radioactive material.

Acton is clear that such “doomsday” scenarios are very unlikely to unfold. “Not least because the Russians have no conceivable reason to want to attack the reactor,” he tells The Verge. It would be risky for the entire region, especially for Russian ally Belarus that borders Chernobyl. In an accidental strike, it would still be unlikely that the cooling pools or casks would be catastrophically damaged. Even then, there would be some time to react — potentially dousing the exposed fuel with water to keep it cool.

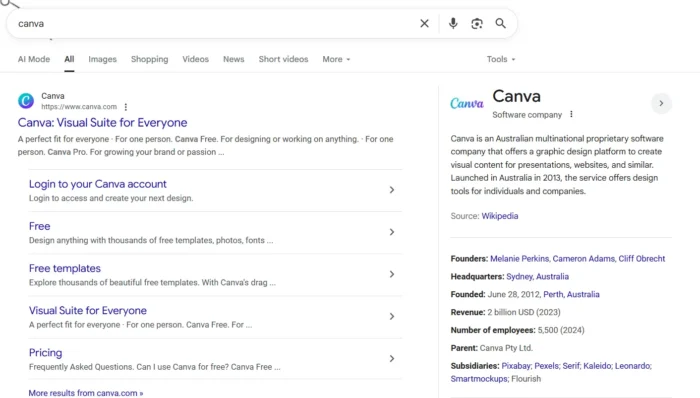

On top of that, much of the area surrounding Chernobyl is desolate, with very few people who might be affected by any smaller-scale event. The region was evacuated in the wake of the 1986 disaster and remains a cordoned off Exclusion Zone.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23269323/1192405627.jpg) Abandoned amusement park in ghost town Prypiat in Chornobyl exclusion zone. Ukraine, December 2019Photo by Maxym Marusenko/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Abandoned amusement park in ghost town Prypiat in Chornobyl exclusion zone. Ukraine, December 2019Photo by Maxym Marusenko/NurPhoto via Getty Images

There is still radioactive material in the debris, soil, and leaf litter around the power plant. Rofer says that radioactive material has decayed to the point where it’s not immediately dangerous — although it could potentially still be carcinogenic to people with enough exposure.

That worries Kate Brown, MIT distinguished professor in history of science. Disturbances, human or natural, defy the purpose of the containment zone, which was engineered to keep people away from the area’s radioactivity.

In 2020, smoke from fires that ripped through the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone carried slightly radioactive particles across parts of East and Central Europe. The doses from those fires were “radiologically insignificant and no health impact on the European population is expected,” according to an article published that year in the journal Nature. But Brown remains concerned about future fires and other disturbances that could spread radioactivity outside the exclusion zone.

“It’s a continuing problem,” Brown tells The Verge. “It’s supposed to be contained. It’s supposed to be left untouched. And that’s that’s the problem with any kind of nuclear site. It demands stability and peace.”

Hollif

Hollif