Why is S’pore so determined to raise GST? It’s the best way to tax the rich amid inflation

On the face of it, raising consumption taxes when global inflation is out of control appears to be crazy. But is there a method to this madness? In Singapore, surprisingly, there is.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

On the face of it, raising consumption taxes when global inflation is out of control appears to be crazy. But is there a method to this madness? In Singapore, surprisingly, there is.

Hug the rich

Singapore is ranked the top three most attractive destinations to High Net Worth (HNW) individuals, with about 2,800 of them expected to relocate to the city-state this year, trailing behind United Arab Emirates and Australia.

The wealthiest 10 per cent of local taxpayers are already responsible for 80 per cent of the income tax receipts and the top 20 per cent, along with foreigners, pay over 60 per cent of GST annually.

Source: Heng Swee Keat, 2021

Source: Heng Swee Keat, 2021Given how shaken the economic situation and budgetary balance have been by the pandemic, and the incoming spending demands of an ageing society in the next decade, the government has to find new sources of revenue, despite growing reserves and returns on them.

Because, unlike in most other countries, it cannot borrow money to finance budgetary expenses. It has to be extra frugal, but also extra careful about where it draws money from. Taxing businesses and the wealthy too much may chase them out of the city altogether, leaving them with a Singaporean tax bill of $0.

Another issue is that taxing income of the rich is still particularly ineffective (despite the fact they already are contributing the most). The reason is because they have plenty of vehicles of tax avoidance, which will reduce their liabilities to Singaporean budget. The old adage is, after all, that the rich pay as much in taxes as they want to.

Similarly, taxing wealth — something that certain parliamentarians in Singapore have proposed — is even worse, because there’s no credible way of estimating a person’s global net worth.

Not only is it fairly easy to hide much of it, but it would also be nearly impossible for the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) to put a price on international holdings of wealthy individuals, while the bureaucratic hassle may also discourage them from moving to Singapore in the first place.

Image Credit: Tax Foundation

Image Credit: Tax FoundationWho wants to go through such an ordeal every year? Which is also why most countries which had wealth taxes in the past abandoned them at some point, as it was uneconomical to run the entire scheme.

GST, however, is a different beast

First of all, consumption taxes are pretty much unavoidable. If you live somewhere, you pay them as a part of the price for everything you buy. But at the same time, it makes them relatively painless.

It’s just a portion of a purchase you get to enjoy, rather than a monetary transfer (like an income tax bill) that you don’t get anything in return for (at least not directly).

Luxury cars parked in front of the Fullerton Bay Hotel / Image Credit: pavelvero @ Depositphotos

Luxury cars parked in front of the Fullerton Bay Hotel / Image Credit: pavelvero @ DepositphotosThe rich are willing to splurge in Singapore, as the recent record-breaking COE auctions have shown or the headline-grabbing rental fees — in one case, S$200,000 per month for a Good Class Bungalow — that some newcomers have agreed to pay (before spending millions on decorating the place).

Inflation inflates the budget too

Another welcome side effect is that as inflation increases, prices of goods and services also increase, and quite directly, this increases the GST revenue, since it is just a percentage of the price.

The higher the price, the higher the tax receipts.

It would typically be a cause for concern, as it adds even more to inflation. But in Singapore, this problem is addressed through active redistribution of the proceeds to the general public. Money is quite literally taken from the rich and given to the poor (and even the not-so-poor too).

The rich are funding tax relief for everyone else

This is why the Singapore government was able to announce a S$6 billion GST relief package that will de facto offset real GST increase by five to 10 years for low- to mid-income families, and reduce the burden of the tax for everybody else other than the wealthiest (as I explained in an article a few months ago).

Below, you can see the real effective GST tax rates depending on housing and income situation after the full increase to nine per cent, not including the government relief packages.

Source: Own calculations, based on government data

Source: Own calculations, based on government dataIn other words, the bottom half of the society or so will pay, in real terms, no additional GST for the next few years. Once the reliefs expire, the real increase will be closer to 1 to 1.5 per cent, rather than the full 2 per cent.

In fact, most people don’t even pay the full 7 per cent in the first place (and won’t be going forward).

How can the government afford to keep giving handouts?

In addition to the S$6 billion announced earlier, MOF has announced another package to offset the raging inflation, amounting to S$1.5 billion in various handouts this year.

In total, that’s already S$7.5 billion that we can expect to be spent in the next five years.

At this point, you may be asking yourself how does that make sense? The government says it needs more money and yet it keeps spending more to reduce the impact of the tax hike it itself announced? Sounds crazy.

And yet, the net effect will be positive to the budget — that’s why there’s plenty of money to spare.

A full 2 per cent increase from 7 to 9 per cent was expected to bring around S$3.5 billion each year. It’s quite likely that this figure will now be closer to S$4 billion due to inflation.

Over a five-year period, this translates to an additional S$20 billion to S$30 billion (as economy keeps growing over time, so will the tax revenue) to the budget — with S$7.5 billion currently assigned to tax and inflation relief.

It’s quite possible that more support will be provided if prices remain high, but even so, the net result is an additional S$12 billion to $20+ billion, even after most of Singaporeans have received their vouchers and cash payments.

In other words, the rich are not only paying more into the coffers, but are also shouldering the transition for the rest of the society.

Amazingly, despite this, they still have no reason to flee Singapore, as a consumption tax of just 9 per cent is still very low by global standards.

Even after a full hike to 9 per cent, Singapore will still rank third from the bottom among developed countries, by sales tax rate / Image Credit: OECD

Even after a full hike to 9 per cent, Singapore will still rank third from the bottom among developed countries, by sales tax rate / Image Credit: OECDThis is the beauty of a GST-based solution.

Income taxes have already been bumped to a maximum rate of 24 per cent, which is becoming unacceptably high to the wealthy. Outright wealth tax would likely drive many of them away to greener pastures (particularly jurisdictions like Dubai).

But a GST is still about as low as it gets in most places in the world. The planned hike is inconsequential to the wealthy, but very substantial to the Singaporean budget, while providing enough funds to both improve national finances and help the rest of the society to adapt to the change over the next few years.

‘Mission: Impossible’ without reserves

It’s important to stress that the situation Singapore is in is rather unique. The city-state has been able to keep its taxation system so attractive for so long because it is able to rely on the ROI from reserves invested by Temasek, GIC and MAS.

Image Credit: GIC

Image Credit: GICNIRC (Net Investment Returns Contribution) is now approximately 20 per cent of the budget. Without it, GST would have to be at levels comparable to those in Europe — 21 per cent or more (as I also explained a while ago).

The government would likely also have been forced to take on debt to finance regular spending, like most countries do.

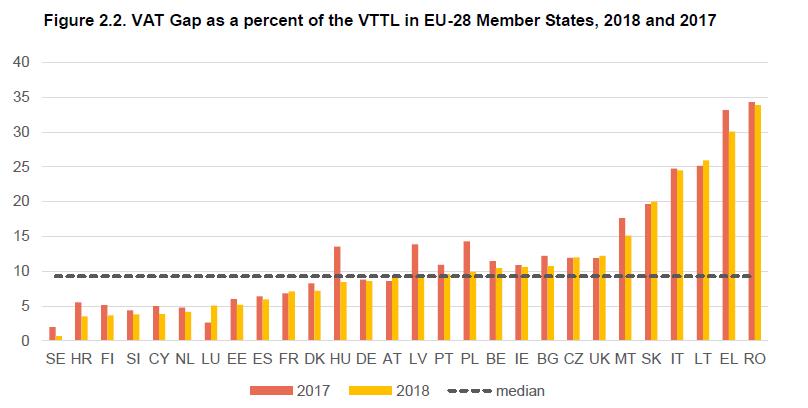

In such a case, trying to squeeze more out of consumers by flirting with GST rates of mid to high 20s would not only fail to produce a desired result, but could also drive them abroad, while forcing the poorer ones into grey market.

Gap in VAT real receipts vs. expected ones. VTTL stands for VAT Total Tax Liability – the expected revenues from the. With higher sales taxes businesses and consumers keep some transactions off the books. / Image Credit: European Commission

Gap in VAT real receipts vs. expected ones. VTTL stands for VAT Total Tax Liability – the expected revenues from the. With higher sales taxes businesses and consumers keep some transactions off the books. / Image Credit: European Commission As a matter of fact, everything would be different. With higher taxes, Singapore would no longer be as attractive a destination for the wealthy either. With lower revenue from both income and sales taxes, it would either be forced to spend less or take on debt to prop itself up.

In other words, it would be just another fairly developed but stagnant, gradually sinking economy like the ones we see in the West or Japan.

Fortunately, it is well-prepared for a crisis like the one we’re going through right now, and is able to raise taxation and shift most of its burden on the wealthy, while (remarkably) remaining highly attractive to them — all of that, while reducing the pain for regular people for at least a few years.

Featured Image: thaneeh / depositphotos

BigThink

BigThink