Wisdom Seeks for Wisdom

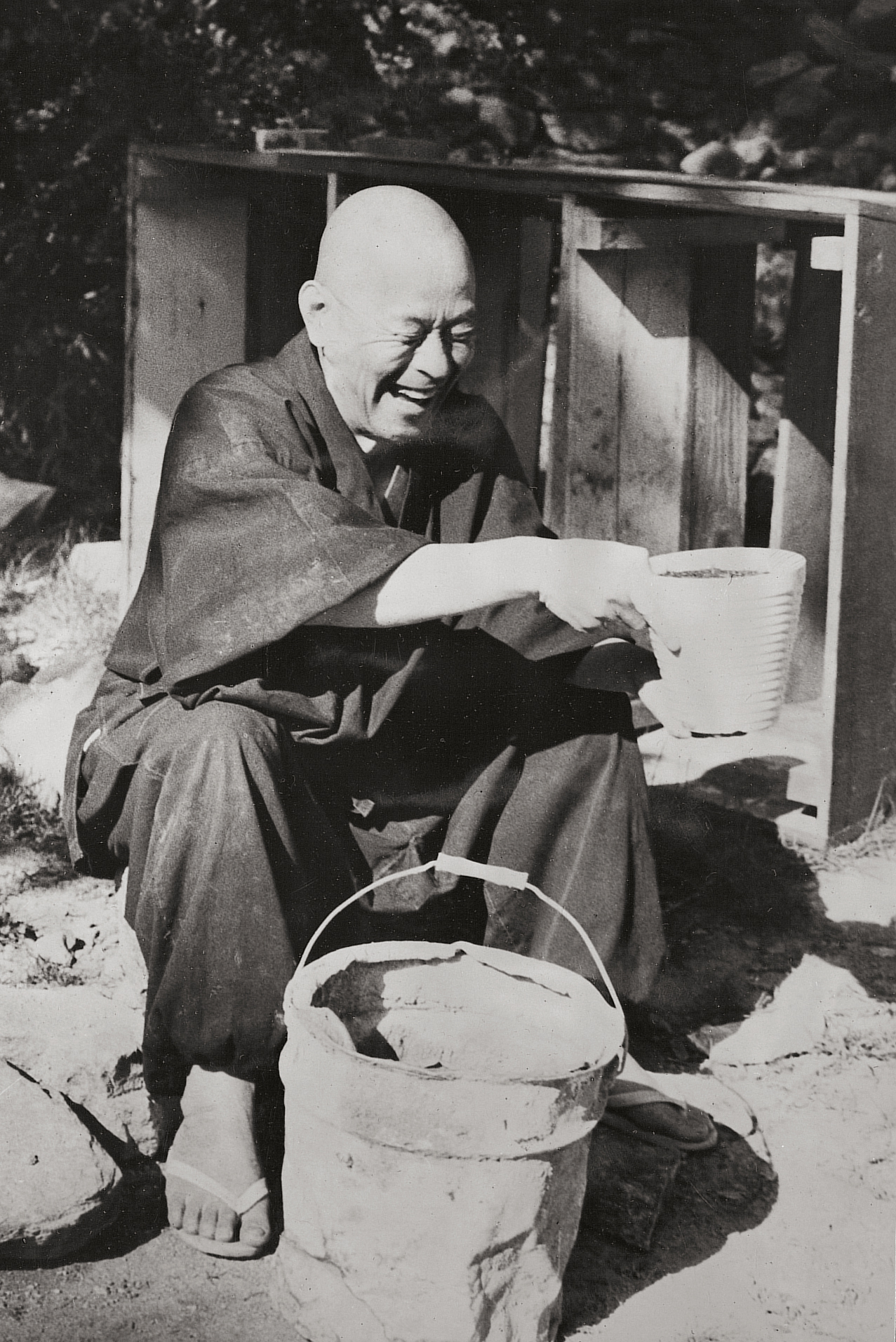

In this teaching from 1965—taken from the oldest extant recording of his talks—Shunryu Suzuki Roshi explains what it means to understand your true nature. The post Wisdom Seeks for Wisdom appeared first on Lion's Roar.

In this teaching from 1965—taken from the oldest extant recording of his talks—Shunryu Suzuki Roshi explains what it means to understand your true nature.

We have been studying the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch—and with it, prajna, or wisdom. But this wisdom is not intellect or knowledge. This wisdom is our so-called inmost nature, which is always in incessant activity. Zazen practice is wisdom seeking for wisdom. “Wisdom seeks wisdom” is zazen practice, and everyday life is wisdom. Realization of our precepts is our everyday life; when our everyday life is based on wisdom, we call it “precepts.”

When we sit, we do not do anything. We just sit. There’s no activity of our mind. We just sit, and all we do is inhale and exhale. Sometimes you will hear some birds singing, but you are not actually hearing. Your ears will hear it; you are not hearing it. Just sound comes, and you make some response to it, that’s all. This kind of practice is called “wisdom seeks for wisdom.”

We have true nature. Whatever you do, even if you are not doing anything, your true nature is constantly working. Even when you are sleeping, it is quite active. Your thinking or your sensations are the superficial activities of yourself, but inmost nature is always working. Even when you die, it is working. I don’t mean some soul, but something—something is always incessantly working. Whatever you call it, I don’t mind. You can put many names to it, or you can give it various interpretations, but the interpretations belong to your intellectuality. That is intellect. So, whatever you call it, inmost nature itself also doesn’t mind. Someone may call it “soul.” Someone may call it “spirit.” Someone may say, “Oh, no, no, that is just material. Soul is some kind of function of materiality.” Maybe. People will put many names to it, but our inmost nature is our inmost nature. Names have little to do with it.

When we sit, we say that it is the self-activity of inmost nature. Let it work—we don’t do anything but let true nature work by itself. This is Zen practice. Of course, even though you do not do anything, you will have pain in your legs, or some difficulty to keep your mind calm. And sometimes you may think, “Oh, my zazen is not so good.” That is also the activity of inmost nature—not your activity, but the activity of your true nature. Your true nature says, “Your zazen is not so good.” If it says so, you should accept it: “Oh, not so good. What are you thinking? Stop thinking.” This is Zen.

When you do something, it has a kind of morality in it. This is because you are doing something by choice. When you make a decision to do something, your inmost nature will tell you, “That will not be so good. Why don’t you do it this way?” That is the precepts, when we have some choice in our activity. In zazen, we have no choice—we just sit, and whatever inmost nature says, let it do it. “I don’t mind.” That is zazen.

But when you make a plan, you are responsible for it. Then, you should listen to what your inmost nature says—it will tell you what to do. If you understand this way, then it is the way of morality. It is the precepts. The precepts are not only two hundred and fifty or five hundred. Five hundred or three hundred—it doesn’t matter. Whatever we do is the precepts, because we have some choice. We have to make some decision.

“I am responsible for it—what I should do?” When we make some decision, we listen to buddhanature: What should I do? That’s all. Here in your everyday life, you have precepts, and you have freedom, too. Whatever you do, that is up to you. As long as you have freedom, you yourself make decisions, so you should be responsible for them. You should not say, “Buddha should be responsible for it. I am not responsible for that.” We cannot say that in our everyday life; we should observe the precepts, instead of leaving the responsibility to Buddha. We should be responsible. But at the same time, we have freedom—there is no need for you to be bound by precepts. Precepts are formulated by your own choice. As long as you have conscious activity, there is freedom, and at the same time, you should be responsible. This is freedom—true freedom.

Someone may say, “Whatever you do, that is buddhanature, so it doesn’t matter what you do.” This is a misunderstanding. Morality without buddhanature is just a moral code, a rigid moral code by which you will be enslaved. If you become aware of buddhanature, innate nature, then that is freedom, not rigid precepts. You do things by your own choice and according to your true nature: complete freedom. That is also morality.

In this sense, you have freedom—you are not enslaved by either buddhanature or a moral code. And our moral code is not always the same. It is not permanent. Strictly speaking, there is a moral code whatever you do. So we say Zen and the precepts are one. In everyday life, we call it precepts; in the practice of zazen, we call it Zen. They are not different; they are both based on the self-activity of inmost nature. This is a very important point.

We bowed this morning nine times. Bowing to Buddha is a kind of practice to get rid of our self-centered ideas, to give ourselves completely to Buddha. Here, to give ourselves means to give our physical and intellectual life to Buddha because it is based on buddhanature. Even if we forget all about it, we still have buddhanature. So Buddha bows to Buddha. That is bowing. This is one meaning.

Another meaning: as long as we live, we have a body here, and we have to think something. Buddha practiced Zen, and we practice Zen, so everyone, when they practice Zen, is called Buddha. And buddha mind, or bodhisattva mind, is our spirit. To attain oneness in duality is, in short, our spirit.

Because we are not so good, we try to improve ourselves. That is our true nature. And we are aware of it—we have some intention to improve ourselves. This intention is limited to human beings. Flowers come out in the spring without fail, but they do not make any effort; they automatically come out—that’s all. We also try to open our flower in the spring, you know. We try to do right things at the right time. But we find it very difficult—even though we try to do it, we cannot. This is our human nature. We always try to do something. We always have some difficulties. But this point is very important for us. It is why we have pleasure as human beings—because things are difficult and we are always making some effort. That effort results in the pleasure of human life, a pleasure limited to human beings. This is called our true nature.

If you understand this true nature, you will find out the true nature within yourself and in every existence. Flowers have this nature. Even when it is cold, they are preparing for spring, even though they do not know they are making a good effort to come up in spring. When we become aware of it, we will know that this nature we have is universal to every existence. Again, this awareness of true nature is limited to human beings, so it is very important. This is the awareness, in short, of trying to do something good. It is our spirit.

We don’t know why we should try to improve ourselves. No one knows. There is no reason for it; it is beyond discussion. Our true nature is so big. It is beyond comparison, beyond our intellectual understanding, so it doesn’t make any sense. Those who are aware of it will laugh at you if you discuss about why it is so. “What are you talking about?” It is too big a problem to discuss. This is why we bow to Buddha.

From the oldest extant recording of a dharma talk by Suzuki Roshi, given in Los Altos, California, on July 22, 1965. Published with permission by San Francisco Zen Center.

Fransebas

Fransebas

.jpg&h=630&w=1200&q=100&v=6e07dc5773&c=1)