You’re Sautéing Your Vegetables All Wrong

Sautéing vegetables is a seemingly simple act. Cut them up, put them in a hot pan, move ‘em around until they’re “done.” But there is a lot of variation from vegetable to vegetable in terms of density, water content,...

Sautéing vegetables is a seemingly simple act. Cut them up, put them in a hot pan, move ‘em around until they’re “done.” But there is a lot of variation from vegetable to vegetable in terms of density, water content, and starch content, just to name a few factors. Making truly delicious sautéed vegetables isn’t hard, but you do have to think a bit. (I know, I hate it too!)

Dry them thoroughly

Whether you’re cooking up a pan of mushrooms or bouquet of broccoli, eliminating extra water from the cooking process ensures you’re actually sautéing, not steaming. Water prevents prevents your food from making good contact with the hot pan, which means less browning, which means less flavor. You can blot your veggies with paper towels, but I like to use a salad spinner to fling every last drop of water off and away.

Cut them uniformly

A 1/2-inch chunk of carrot will cook faster than a 1-inch chunk of carrot. That’s just physics. Slicing and/or dicing your plant parts to similar, if not identical dimensions will ensure they cook at the same rate, so you don’t end up with a pile of carrots that is plagued with both mushy and crunchy pieces.

G/O Media may get a commission

When adding different types of vegetables to the same pan, a good rule of thumb is to add them “from the ground up,” starting with root vegetables (like carrots) and things that grow right on the ground (like squashes), and working your way up to the leaves and flowers that grow avove ground (like cabbage or broccoli).

About those denser vegetables

At the risk of contradicting myself, sometimes it’s not enough to add the tough guys to the pan before the soft bois. Denser root vegetables (like potatoes) and hearty squashes (like butternut) can benefit from little par-cooking (partial cooking) before they hit the pan, so you don’t end up with browned outsides and tough insides.

Bathe your sweet potatoes for better flavor

Serious Eats found that par-cooking sweet potatoes in a hot, but not boiling water bath before roasting resulted in yams that browned better and tasted sweeter than those that were cooked from fresh. You can use this same move for sautéing:

Bring three quarts of water to a boil in a large pot. Add one quart of room-temperature water. This should bring your water down to around 175°F (79°C). Add a few pounds of sliced or diced potatoes to that water, and it’ll come down to well within the requisite range. Pop a lid on the pot, keep it in a warm part of your kitchen, leave it there for a couple hours...

Once the sweet potatoes are done with their bath, you can roast or sauté as usual.

Nuke your butternuts for easier peeling

Butternut squash is notoriously hard to peel and chop, but a few minutes in the microwave can soften them up. Cut three or four long slits into each side of the whole squash (so steam can escape and your squash doesn’t explode), then nuke it in the microwave for three-to-five minutes, until the skin softens. Let sit for a minute or two, then peel and dice like you normally would.

Boil white potatoes to give them better texture

Boiling potatoes for a few minutes cuts down on time spent in the pan while the salted water infuses them with flavor. You can par-cook a bunch of spuds all at once, then fry them throughout the week as the craving strikes. Add 2 tablespoons of kosher salt to 1 quart of water and bring to a boil. Add up to 2 pounds of 1-inch cubed potatoes and cook for five minutes. Drain, then spread out over clean kitchen towels or paper towels and let the excess moisture evaporate for 10 minutes. Sauté immediately or store in the fridge until cooking time.

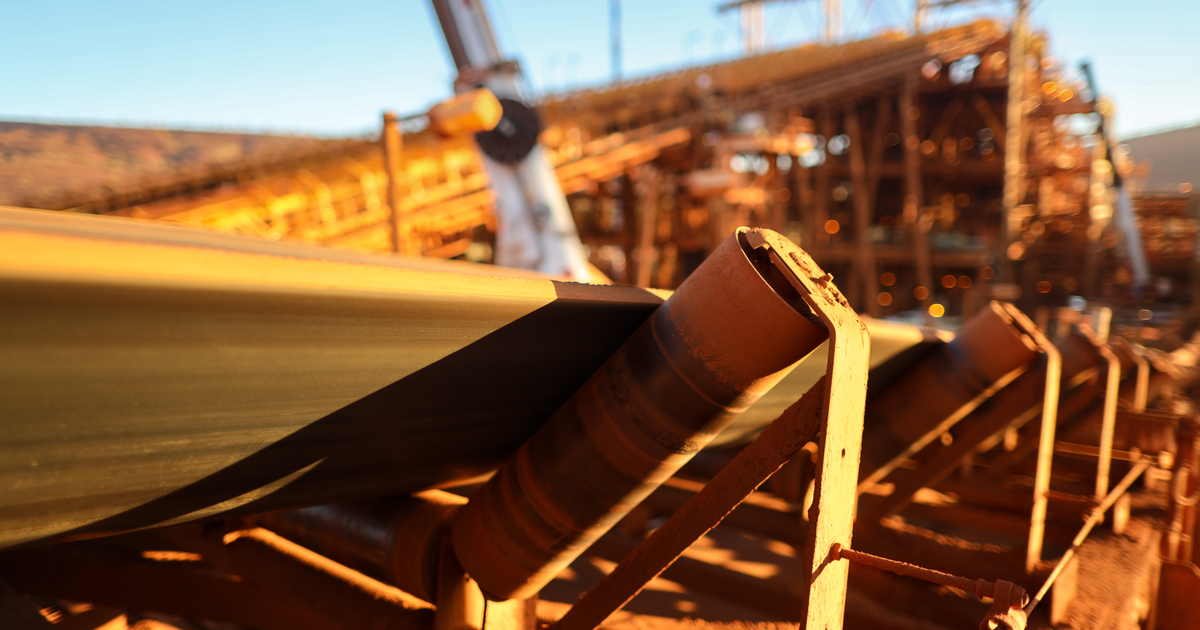

Stop crowding the damn pan

Every single stock photo of “sautéed vegetables” shows a pan that is far too full of vegetables to get any real sautéing done. Those vegetables are steamed, mama, and steamed vegetables are nowhere near as flavorful as their sautéed counterparts.

Adding too much cold food will drop the temp of your pan, and a cold pan cannot sear. You want to use a pan that’s big enough to let everyone hang out in a single layer without touching or overlapping, so they get as much contact with the pan as possible, and the water has room to evaporate quickly.

Make sure your pan is hot

Sautéing is a high-heat cooking method, so you want your pan to be sizzling. You want your oil to shimmer, your butter to foam. (Eliminate the fat for mushrooms though. Mushrooms play by their own rules.) A good way to test this is to flick some water in there. If the water sizzles and evaporates immediately, you’re ready. (You do not, however, want the pan so hot the water rolls into a little ball and dances around the pan. Save that for steaks and chops.)

Stop fucking with it so much

Sautéing is an action, yet some people are a little too active. Resist the urge to constantly stir and scoot and let your vegetables remain in contact with the pan long enough to develop some color. Color is flavor, friends—let it happen.

ShanonG

ShanonG