Zen Is Not a Democracy

Brad Warner discusses ethics, Zen, and his new book The Other Side of Nothing The post Zen Is Not a Democracy appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

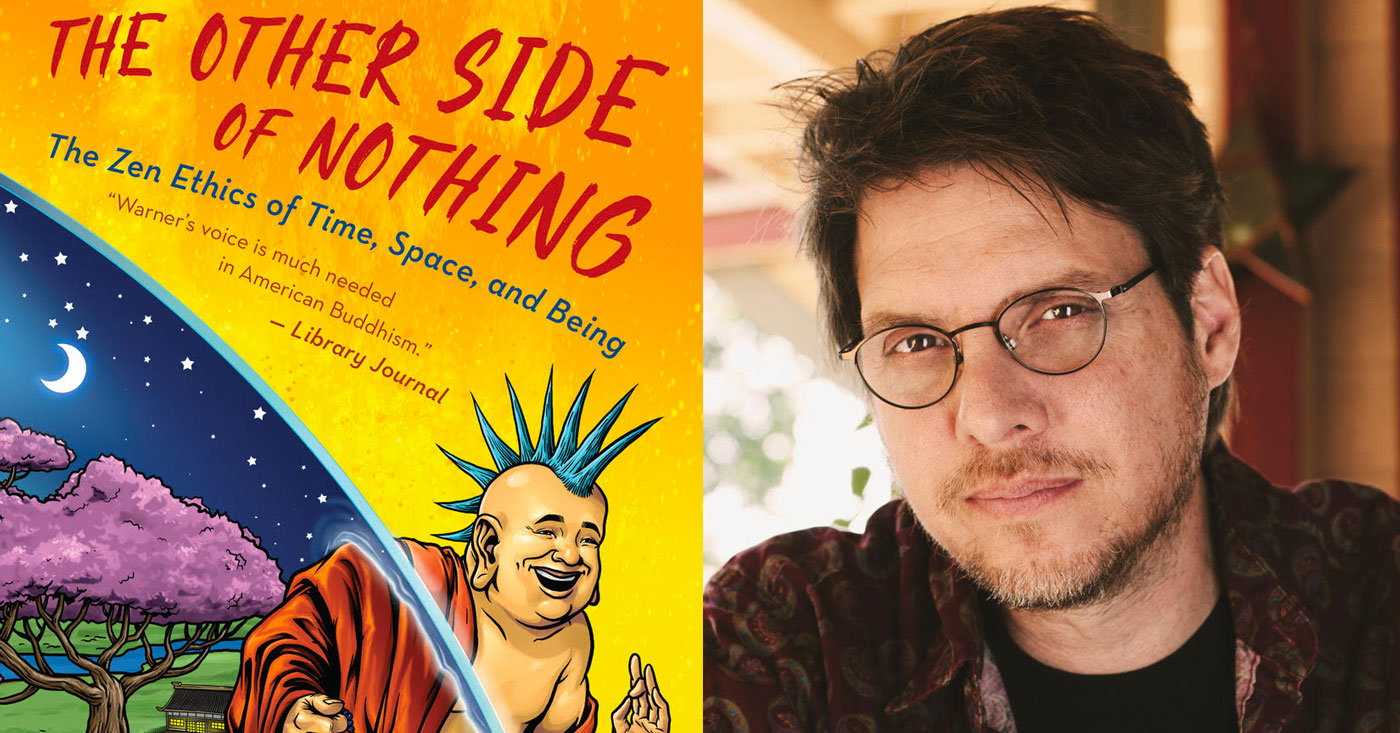

Photo courtesy Brad Warner

Photo courtesy Brad WarnerBrad Warner has been a notable figure in Zen in the West since the publication of his first book, Hardcore Zen, in 2003. His blog of the same title was a prominent landmark in online Buddhist discourse as Buddhist communities ventured online two decades ago. Warner is a bass guitarist in a punk band, and his teaching style often has an irreverent exterior.

On the cover of his new book, The Other Side of Nothing (New World Library, May 2022) the Buddha sports a spiky blue hairdo. This tongue-in-cheek presentation is matched by Warner’s laidback writing style. But his approach to the dharma, if not exactly orthodox, is deeply rooted in texts and tradition (Warner is a dharma heir of Soto Zen priest Nishijima Roshi.)

Warner has also been a vocal critic of dharma “innovations” such as the use of psychedelics as an aid to practice, and remains skeptical of online teaching. He was vocal about problematic power differentials in our 2011 interview but still insists that Zen communities cannot function when run by committee. He recently left the center he founded in Los Angeles, Angel City Zen Center. I spoke with Brad in early March 2022 about his new book on Buddhist ethics, the importance of following tradition—even the parts that don’t always make sense to modern practitioners—and his future as a teacher.

—Philip Ryan

***

Tricycle: In your new book you tie ethics to nonduality and argue that behaving unethically is hurting ourselves. We may think acting unethically is selfish, but you’re saying it’s much more than that: It’s nonsensical. Can you lay out that case?

Brad Warner: It’s funny, I’ve gone so deeply into the book that I’ve gone straight through and come out the other side! I’ve forgotten what I put in and what I left out. There was one thing I kept trying to write for years, I don’t know if I decided to put it in or not. It’s the concept of enlightened selfishness, that the best thing you can do for yourself is to be decent and kind to others. If you want a good life, a truly good life for yourself, then your best bet is to be good to others, because there’s essentially no separation between all of us. Anything you do to somebody else, you’re actually doing to yourself.

When I first heard the precepts, I heard them as admonishments. Like, there’s a bunch of fun stuff you could do and gain a lot but you better not do that because that wouldn’t be good! And then I came to realize that’s not the case at all. The precepts are actually telling you how to have a better life. Just don’t do these things, and you’ll actually enjoy your life more. Anything you do to somebody else is harming yourself. Another way of saying it is that it’s good to be careful.

Tricycle: Westerners sometimes come to the precepts with ideas about the 10 commandments. They hear the precepts and think, oh, no, that’s not what I want in Buddhism! I’m here for the freedom.

BW: There are parallels with the 10 commandments. Several of the precepts are the same as the 10 commandments, but the attitude is different. The precepts are not presented as coming from God who must be obeyed, and whose opinion is right because He’s God. In Monty Python and the Holy Grail, God appears to them and they say, “Good idea, oh, Lord,” and God says, “Of course, it’s a good idea, I thought of it!”

But when we understand that the process of how the precepts came about we see it’s different. When the Buddha had his original sangha, they basically started out with no rules, and then as things came up, they created rules, and that’s the basis for the precepts. It’s understood that they’re made by people, but even so they’re not arbitrary. They’ve been honed for a long time.

My teacher used this analogy, and I have mixed feelings about it, but I’ll give it to you anyway. We’re like cows in the pasture, or sheep. And as long as we’re in the fenced-in pasture, everything’s fine, because the predators can’t get to us. But when you go out of the fence, then you’re in danger, then things can happen and things can go wrong. You’re putting yourself at risk. I don’t like to compare people to sheep, or cattle, but maybe the analogy still works.

Tricycle: How is it helpful to understand “we’re all one,” when you’re in the middle of a disagreement with someone? How do we use that?

BW: Ultimately you can’t use it. By that I mean that you, as an entity apart from whoever you are disagreeing with, can’t use that understanding. You, as an entity who uses your understanding, has to step aside. This is easier said than done for most of us. In a conventional way I guess you could keep in mind that your opponent is really just an aspect of yourself, metaphysically speaking. That might work. I think it can be helpful to do that. It can be useful to conceive of things that way. But what I’m really saying is you have to let go of yourself completely.

In my book Sit Down and Shut Up I told the story of how I was having an argument with my then-wife. I can’t remember what we were arguing about. But there came a point where she said something and I thought of the perfect “winning” response. There’s an episode of Seinfeld in which George comes up with a killer comeback to something one of his co-workers said. But he thinks of it too late. So he keeps trying to get the co-worker to say the same thing again. In this case, I thought of the killer response right then. How often does that happen? But I also saw that, in winning the argument, I’d end up creating a lot of resentment and bad feeling. So I shut up, and said nothing. I dropped my desire to be a winner and accepted that saying nothing was the better way. The argument just kind of fizzled out then and we both felt a lot better. That kind of thing is really difficult, but it’s incredibly worthwhile, I think.

Tricycle: Do you think ethics are fundamental to us? Are they something that we rediscover as we look at the precepts or are they something that comes from the outside that we need to fence in our chaotic natures?

BW: I think it’s a bit of both. I think we have a natural desire to be ethical. We can overcome that if we think there’s something to be gained by overcoming it. But when I examine myself, it seems like every time that I act unethically in order to gain something, I don’t actually gain anything. As far as whether it has to be imposed, I don’t know. I think everything has that aspect to it, external and internal. It’s like the question of why you need a teacher. This comes up in Buddhism a lot. Dogen always emphasizes this need to have a teacher.

I’ve been studying the Advaita Vedanta tradition lately. I got on a kick a couple of years ago to look into it, and they have the same idea of the guru. They frame it differently, but it’s still an outside thing and they actually have terminology for it. There’s the guru that’s inside and the guru that’s outside, but in their way of framing things they’re one and the same. I don’t see that exact way of explaining it in Zen but I do feel like it’s a similar idea. I needed to have an external teacher to awaken the internal teacher that was already there.

Buddhist ethics are based on an intuitive sense that is difficult to come by. This is one of the reasons we meditate. Zazen or whatever meditation you choose is usually good for clearing away all the other stuff, all the thoughts and things. Thought comes in and muddles things up, and it’s not that you have to try to stop thinking. What’s more useful is to learn to stop believing your own thoughts, because you don’t really have all that much control over your own thoughts.

I think Sam Harris said this, that I can no more predict my next thought than I can predict your next thought. We imagine that we have control over what’s going on in our heads, but we don’t. Maybe we have a tiny bit of control, but not very much. The best strategy, I think, is just to learn to let go. It’s just more noise, you know, it’s like there’s people arguing next door and you can listen in on the argument or you can ignore it. If it’s a really loud argument, it’s hard to ignore. A meditation practice will help you get to the point where the thoughts, even though they’re still happening, are less distracting. They’re just background noise.

Tricycle: I was struck by your chapter on confession. How important for maintaining our ethical behavior are other people, or what we think that other people think of us?

BW: It is important because we’re built that way. It’s probably something to do with being a primate. Your instinct is to live in a social group and look at the other members of the group for clues on how to behave and what’s acceptable and what’s not. We do seem to need that. I didn’t set out to write about confession, but when I decided to write about the precepts, that was a big part of how the precepts in Buddhism developed. There was a system of confessing your wrongdoings to the group which has largely disappeared. But in the early days of Buddhism, that was a big deal. It’s developed into a formula:

All my ancient twisted karma

From the beginning, this greed, hatred and ignorance

born from body speech and mind

I now fully avow

It’s a general acknowledgment that you’ve done something, but you don’t have to say specifically what you did. This saves you some embarrassment and I think it’s probably fine if you keep those things private. But it was useful for me, sometimes, to talk to my teachers about specific things I’d done one-on-one and say, here’s what’s going on. And my teachers were always like, “Oh, don’t worry about it.” It’s funny that “Don’t worry about it” can have a whole different meaning when it’s coming in a different context.

You understand that what you did in the past was not what you should have done. And then you make an effort not to do that again. The sixth precept is usually given as “Don’t criticize the faults of monks and Buddhist laypeople,” but the version I learned was “No speaking of past mistakes,” which means not just the mistakes of others, but your own mistakes. You don’t need to dwell on your mistakes, but you need to see that you did them, and make an effort not to do them any more once you realize they’re wrong. Dwelling on past mistakes is just a way to inflate your ego. You inflate your ego through negative things as much as by positive things. I’ve noticed that I’m much more inclined to inflate my ego with negative stuff. Because I’m so bad. I’m so wrong. I did that terrible thing. It’s me me me, so it reinforces that sense of self. And I find myself doing that much more than the other version of being egotistical, which is, I’m the greatest thing in the world. That one doesn’t work as well for me.

Tricycle: You’ve been a consistent critic of drug use over the years, back when people were talking a lot about psychedelics, which is still going on. But in this book, you talk about how it’s important not to use meditation itself as an intoxicant. Do you mean that you can get addicted to it?

BW: I meditate twice a day every day, rain or shine, so you could think I’m addicted to it. And I feel weird if I don’t do it. But no, I think the problem where meditation becomes like a drug happens more often to people who don’t have a teacher. You can get very indulgent in your own fantasies. If your fantasies happen to match what you might read in certain meditation literature, then you can get really suckered into it. It’s good to have somebody outside to balance that out. And it might be necessary to have this corrective at some point in practice. Anybody is going to encounter these situations where it’s exactly what you wanted. When you get exactly what you wanted out of meditation, sometimes that’s a good thing, but often, that’s not a good thing.

It can be very seductive. It’s like your own virtual reality that you’ve created, which is better than any virtual reality somebody else could create, because you tailor-made it to yourself. I see a lot of people go wrong that way. You can look at cult leaders, for example, as evil manipulative people, but often, I think they’re just as seduced by it as anybody else. They get so into the thing, that they start to believe their own fantasies, and then start to propagate their own fantasies. And it can get crazy.

Tricycle: You recently left Angel City Zen Center, which you helped found. Can you talk about that, and what’s next for you in terms of being a teacher?

BW: I don’t want to say too much about that. I just felt like it wasn’t working. It still exists, the Angel City Zen Center, and God bless them on what they’re doing. But it wasn’t working. I felt like a mascot instead of a teacher. I felt like Scooby Doo: His name is on the show, but nobody really listens to what Scooby Doo has to say. He’s just there to be funny. And that’s the way I felt.

In the whole Zen center system there’s a sense in which keeping the community happy is the important thing. But my teacher said something which would probably rankle all Americans who hear it. He said, a Zen Buddhist sangha can never be a democracy. He was really firm about that. I’ve found that if you want to have a Zen center in America, people will insist on it being a democracy. And I’m saying, it can’t be a democracy, because not everybody understands everything equally. And if you let everybody make the decisions, it gets wonky. I don’t want too many people to hate me for saying that, but I read Shoes Outside the Door and I can understand why the San Francisco Zen Center now has three abbots instead of one. But at the same time, you’re diffusing things a lot when you do it that way.

I’ll continue to do what I do. I have a YouTube channel, and that’s been really interesting, because I think something is coming through there. But I also think there’s an entertainment factor. And I don’t really mind it, because it’s YouTube and it’s all about entertainment. So I’m providing what I hope to be a better sort of entertainment, but it’s still entertainment, it’s still trying to put on a show.

There is a guy I’ve been talking to locally about starting another sort of sitting group. But I want it to be less of a Zen center and more of a speakeasy where not only is it not advertised, you have to know the secret code word to even get in. Once you establish something where having butts in seats is a necessary part for keeping it going, then you run into a lot of tendency to compromise. And I don’t want to compromise the things that shouldn’t be compromised, but I want to be able to compromise the things that should be. So it’s like that Alcoholics Anonymous prayer: Lord, let me know which things should be compromised and which shouldn’t, and how to tell the difference.

Tricycle: In the book you say that we’re punching ourselves in the face when we act unethically, because we’re all one. But at this cultural moment it feels like other people are punching us in the face, too. Maybe it’s always been this way. How are you seeing things these days?

BW: I don’t know how much of that is new. Is anything new? One of the weird things that’s happening with with social media is we’re being exposed to the inner thoughts of a lot of people and we’re seeing things that would normally go unexpressed, One of the first things I got involved with on the internet came out in the late ‘90s or early 2000s on the Cleveland punk scene. They had a forum called the bathroom wall where the idea was that you’re writing graffiti on the bathroom wall. And ever since then, that’s the way I think of all these technologies. Twitter is like this big electronic bathroom wall where people think they’re in their stall and nobody can see them and they write terrible things on the wall.

In the past, 1,000 or 10,000 years ago, you had to actually say the thing right in front of the person and then you might get punched in the mouth. But now everybody’s inner thoughts are all out in the open. I think we’re confused by that. We haven’t figured that out yet.

Tricycle: Someone said, probably on Twitter, that our brains weren’t built to process all the world’s emergencies at one time. So we’re exposed to an unfiltered stream of other people’s anger, greed, and delusion, with horrible news from around the world mixed in with pictures of dogs and cats.

BW: I always go for the dog and cat pictures. I’m old enough that I’ve lived through several crises where the world was about to end, so I’m less inclined to believe the next world-ending thing. Maybe one day I’ll be wrong, but I won’t know it because we’ll all be gone! Maybe this is just a step in our evolution, that opening up of everybody’s inner thoughts? And then we have to figure that out. People ask me all the time, have I seen this or that in the news. And you know, what am I gonna do about it? The bottom line is you can’t do much. Maybe someday we’ll establish contact with other planets. And then we’ll start getting news from Regizvan-11 or something. Oh, my God, there’s a war on Regizvan-11! It’s 25 light years away, but I’m so concerned about it. It’s natural to be concerned and to have empathy with your fellow human beings. But you also have to step back and say, there’s nothing I can do about it. I don’t want to be ignorant of it, or be dismissive or flippant about it, but there’s only so much I can do to stop global climate change.

Tricycle: You talk about letting go of your collections, particularly your record collection, in the book. What collections have you held onto?

BW: Not much! I kept all my Buddhist books, because I need them for reference when I’m writing. And I kept some of the really special records that were meaningful to me. And now I’ve bought a bunch more since, so, oh well, but it felt good to unburden myself from some of that.

I worked for a company that made Japanese monster films for a long time and I had a pretty good collection of memorabilia. I called up a friend of mine who’s even more of a collector than me, and I said, just come down and I’ll leave and you can hang out in my apartment for however long you want, and just take anything you want. And he came down with a pickup truck and he filled it up.

I did ask for a couple of things back, but mostly, it felt great. It was one of the biggest highs I’ve ever had, which made me feel like maybe this isn’t so good. But I was so happy to be able to say, ok, it’s gone. Occasionally I remember something that I used to have and I think, ah, but then that feeling goes away. It’s just like one of the things you learn when you’re meditating. The biggest feeling that you have will eventually just fizzle out after a while and you don’t really have to do anything about it. You just say, Yeah, I remember that I had that. Ok.

Tricycle: The neighbors next door will stop arguing, eventually,

BW: Yeah, eventually, they’ll have to go to bed.

♦

Get Daily Dharma in your email

Start your day with a fresh perspective

Explore timeless teachings through modern methods.

With Stephen Batchelor, Sharon Salzberg, Andrew Olendzki, and more

![]()

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.

This article is only for Subscribers!

Subscribe now to read this article and get immediate access to everything else.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Tricycle is the leading independent journal of Buddhism in the West, where it continues to be the most inclusive and widely read vehicle for the dissemination of Buddhist views and values. By remaining unaffiliated with any particular teacher, sect, or lineage, Tricycle provides a public forum for exploring Buddhism and its dialogue with the broader culture.

Hollif

Hollif