A Buddhist Reading of “A Christmas Carol”

Estefania Duque explores how Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol offers timeless dharma lessons on karma, compassion, and transformation through the lens of Buddhist practice. The post A Buddhist Reading of “A Christmas Carol” appeared first on Lion’s Roar.

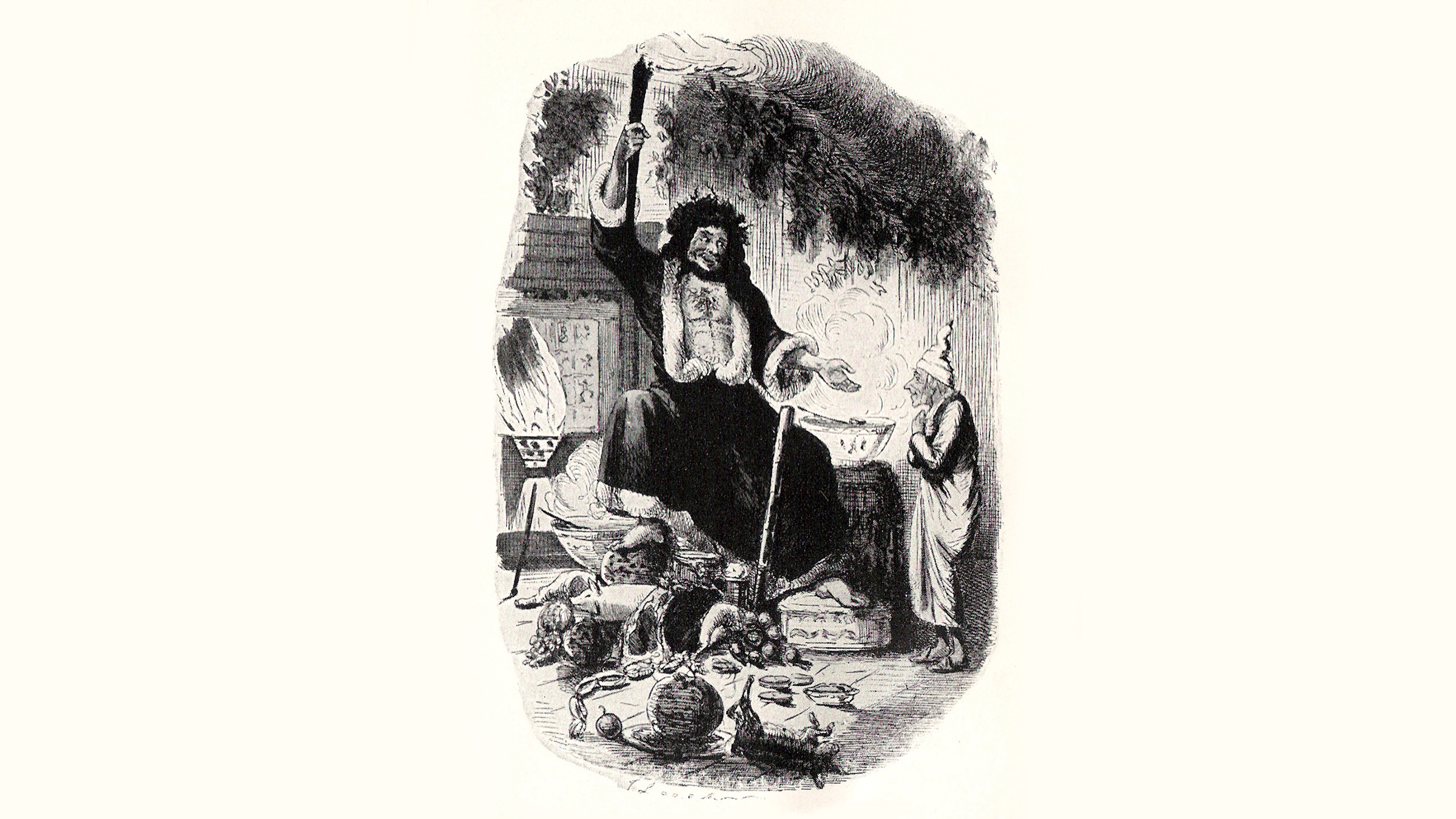

You’ve likely encountered some version of Charles Dickens’ 1843 A Christmas Carol in your life, where the infamous Ebenezer Scrooge despises the holidays and obsesses over money. That is, until one fateful year when he is visited by his late business partner and the “Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come,” warning him of the karmic consequences of his actions. As a Buddhist practitioner and a literature lover, I am always looking for dharma teachings within a story. A Christmas Carol is perhaps the ultimate holiday example.

In the beginning of the story, we meet Fred, Scrooge’s compassionate nephew, the first to try and nudge him toward change. Fred’s kind and compassionate approach doesn’t seem to move his uncle at all, so we see more “aggressive forces” come into action. The first spirit to visit him is Jacob Marley, Scrooge’s deceased business partner. Jacob tells Ebenezer about how his own attachment has created a “chain,” which Buddhists might recognize as karma itself:

“I wear the chain I forged in life, (…) made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. (…) would you know (…) the weight and length of the strong coil you bear yourself?”

Marley insists that a life of loving-kindness, generosity, and virtue is the ultimate path to follow, warning Scrooge that otherwise, he might end up a ghost like him. Indeed, there is no guarantee of where we will be reborn. To attain a precious human life, one of freedom and opportunity turned toward the ultimate goal of achieving the same wisdom and compassion as the buddhas, we must heed such warnings. That’s what Marley might call “our real business,” something that a bodhisattva strives toward.

Warned and scared, Ebenezer realizes he needs to change. With the help of what we might understand as his “demons” — manifestations with a sole mission to guide him toward the path of good — he embarks on a transformative journey. In the Buddhist view, these demons could be seen as wrathful deities, who though frightening in appearance, aim to guide us toward enlightenment.

Scrooge’s journey then begins with the Ghost of Christmas Past, who shows him himself as a sad, lonely child. When the Spirit sees him cry and asks why, Scrooge replies that he had recently rejected a child singing a Christmas carol and now wishes he had been generous to him. It turns out, he’s learned, that the people he views as worthless aren’t so different from him. Scrooge sees that the pain he endured as a child lingered in his heart, shaping his present life. To me, this aligns with the Four Noble Truths: suffering exists, has a cause (ignorance), can be ceased, and the Noble Eightfold Path shows the way. Recognizing the roots of our trauma in accordance with the Second Noble Truth — as Scrooge must — allows us to confront and dissolve it, paving the path to happiness.

Not all of Scrooge’s past was bleak. He fondly recalls his sister’s love and joyous holiday moments at Mr. Fezziwig’s ball. Though a businessman, Fezziwig led his apprentices and employees with loving-kindness. When the Ghost of Christmas Past questions the worth of Fezziwig’s generosity, Scrooge declares that bringing happiness to others was its true value.

Next, the Ghost of Christmas Present appears, and Scrooge is more willing to go with him this time. This reflects what happens when we begin to practice the dharma: the more we are open to introspection, the more we come to the safe space of the present. We realize we have more to gain from insight and meditation than from scurrying away from the past or living in the future.

Sometimes, however, we look for someone else to blame for the world’s suffering. When Scrooge asks the Ghost of Christmas Present why he and others like him allow pain and suffering to exist, the Ghost replies that the fault lies with humans who claim to embody noble values but commit misdeeds. The Ghost urges Scrooge to focus on changing human actions rather than expecting external forces to intervene.

Often, we forget that we’re supposed to embody our own beliefs. It’s not about looking outwardly and wondering why buddhas and bodhisattvas allow for misery to take place in the world — we know that’s beyond them. If we believe the world should be good, it’s our duty to be that good ourselves.

When Scrooge is taken to see his clerk Bob Cratchit’s family, he observes as they rejoice over a humble meal. Moved by the scene, especially by Bob’s handicap son with a heart of gold, Tiny Tim, he pleads that the Ghost tell him if he will live, but the Ghost answers no. Scrooge is horrified, but the Ghost reminds him not long ago he himself had been indifferent to other people’s death.

In Mahayana Buddhism, we often pray: “May all mother sentient beings, limitless as the sky, have happiness and the causes of happiness...” We say these words hoping that all beings will be free from suffering. Thinking of all beings in this way puts things into perspective. When we think about a stranger, we might not care as much, but when we think of someone as a mother, it’s a game-changer. Not knowing someone personally doesn’t mean they don’t deserve to be happy.

When I practice Insight meditation and observe my misdeeds, I like to reimagine things as if I had conducted myself wisely. This happens to Scrooge as well when his heart softens, and he reflects: “He might have cultivated the kindnesses of life for his own happiness with his own hands.” He comes to understand the role he has played in his own experience of happiness — or lack thereof.

The Ghost shows Scrooge his nephew celebrating Christmas and wishing him well, then a mosaic of fellow humans — some of them sick or in jail — but all able to find joy. If something like material gain was inherently the cause of ultimate happiness, as my teacher Lama Tony Karam would say, everyone who ever had it would be so. By that standard, Scrooge would have been joyful. Likewise, if something was the genuine source of suffering, like illness and prison, then the spirit of Christmas glee would never appear. What a wonderful reminder of emptiness.

Later, Scrooge notices two strange children at the Ghost’s feet. “This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want,” the Ghost says. “Most of all, beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.” Here, Dickens signals the poisons of ignorance and attachment, emphasizing that ignorance is the source of suffering unless we do something about it.

Finally, Scrooge meets the Ghost of Christmas Future. Unlike the others, this ghost doesn’t show a face, doesn’t speak, and appears much darker. Like the future itself, the ghost embodies a mysterious uncertainty. “I fear you (…) But as I know your purpose is to do me good, and as I hope to live to be another man from what I was, I am prepared,” Scrooge tells the final ghost.

In the Christmas of the future, death has caught up to Scrooge. No one is left to miss or mourn him. Though he refuses to see his own lifeless face, he glimpses his name carved on a tombstone. That moment is enough to transform him:

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead (…) But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change.”

Karma is composed of causes and conditions. The causes were there, but it was not too late to purify them. After his experience with the ghosts, Scrooge wakes up determined to transform himself. He has been endowed with the Four Powers: Support (he has motivation for wanting to change and a support group to help him through it), Remorse (he regrets his actions), Antidote (he is about to try and make up for all his misdeeds), and Resolve (he will never be the same again).

Scrooge rushes to the streets, shows kindness and joy to everyone around him, buys a large turkey and gives Bob Cratchit a raise (changing Tiny Tim’s fate so that he will no longer die young), and spends Christmas at Fred’s. We can infer from this ending that when Scrooge does eventually pass, he does so with peace and generosity in his heart, surrounded by people who love and miss him.

Dickens finishes A Christmas Carol magnificently: “And it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well.” For a wish of loving-kindness and equanimity, he adds: “May that be truly said of us, and all of us!… God bless Us, Every One!”

Estefania Duque has a degree in Modern Languages and Interculturality from De La Salle Bajío University. She grew up in the warmth of the Buddhist community of Casa Tibet México and is currently completing the Dharma Sagar Translator Training Program with the aspiration of translating the Dharma directly from Tibetan into Spanish.

BigThink

BigThink