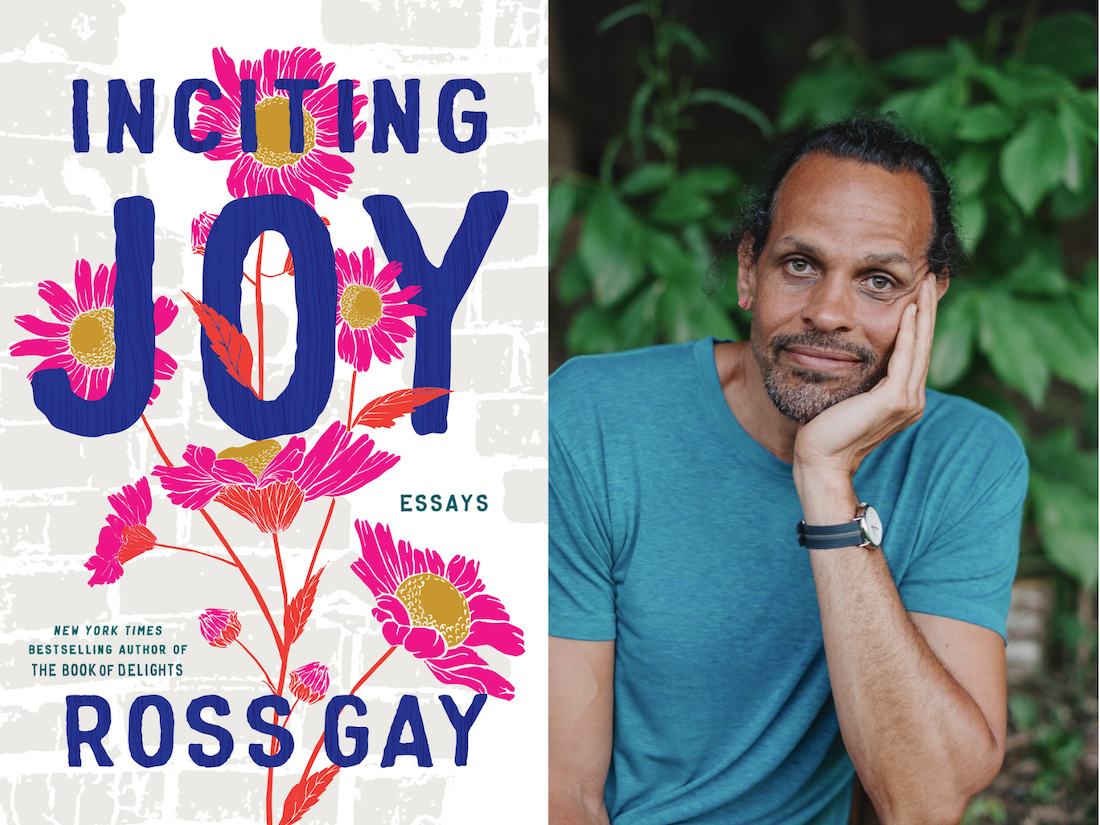

A Radical ‘Joyning’

Ross Gay’s new essay collection reveals a truer, more tender definition of joy. The post A Radical ‘Joyning’ appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

Inciting Joy, poet and professor Ross Gay’s latest inquiry into happiness, reads like an intimate conversation with a close friend. With his usual playful, openhearted wisdom, Gay explores what incites joy and what joy incites through subjects like basketball, dancing, and losing your phone. The word “incite” is often used alongside something like a riot or a revolution, but it’s just as apt for Gay’s definition of joy: a force that dissolves our deepest systems of order—“me,” “you,” “good,” “bad”—and embraces the sweet complexity of what’s left.

Sorrow is inextricably bound up in Gay’s definition of joy. In the first chapter, Gay describes this with a scene almost identical to the night before the Buddha’s enlightenment when Mara attacks him beneath the Bodhi tree. The assault finally ends, as the story goes, when the Buddha says, “I see you, Mara,” and invites him to sit down for tea. Gay’s version adds one more step: Invite your friends and their demons (he calls them sorrows) to the table too and make it a party. This “potluck of sorrows” places communion and interdependence at the center. Joy isn’t the lack of pain but the presence of love.

If joy happens when the borders of the self dissolve, suffering happens when they harden.

Gay addresses the traditional beliefs about joy, namely that it’s confined to accomplishments and possession: the big raise, a new car, organizing that pernicious storage closet, or “getting the dishes sparkling clean.” “It is sad, so goddamn sad—that because we often think of joy as meaning ‘without pain,’ or ‘without sorrow’… not only is it considered unserious or frivolous to talk about joy, but this definition also suggests that someone might be able to live without/free of heartbreak or sorrow.”

In the chapter “Death: The Second Incitement” Gay explores his father’s cancer and eventual death. Amidst the tragedy is a tender, enduring caretaking between the father and son. The litany of pains and indignities his father suffers (being too weak to open a water bottle, vomit stains on his clothes) chips away at the ice block between them. “It was through my tears I saw my father was a garden. Or the two of us, or the all-of-us… And from that what might grow.” Illness forces us to face the reality we all exist in—we know how this ends, or more aptly, that it will. Although not all of us look after someone right up to the end, we’re all caring for the dying. From that, what might grow?

The essays on skateboarding, poetry, comedy, and academia that follow are a cartography of connection. “Despite every single lie to the contrary, despite every single action born of that lie,” Gay writes, “we are in the midst of rhizomatic care that extends in every direction, spatially, temporally, spiritually, you name it.” Each incitement enumerates the ways we brush against each other: We imitate a pro’s three-point shot, we let a classmate look at our exam, we offer a high five to a stranger.

Or we plant a garden. Gay frequently touches on his experience planting the Bloomington Community Orchard alongside a group of go-getters who transformed a barren lot into a hundred yards of fruit trees. Digging into the soil side-by-side (whose hand is whose becoming less important) to nourish seeds and saplings so they can, in turn, nourish a community—that is interdependence.

Holding each other while we fall apart, Gay says, is another word for joy.

Caretaking, a “radical joyning,” happens when we soften the boundaries around the self. A community garden can just be another hobby, but when every mouth that enjoys a ripe mulberry is your mouth too, it becomes something much more beautiful. In a story about dancing to Kendrick Lamar in a sweaty basement, Gay describes how the crowd became “amoebic, hive-ish,” how “‘each other’ got murky.”

If joy happens when the borders of the self dissolve, suffering happens when they harden. An essay on Gay’s college football career shows how hypermasculinity backed by violence shrinks who the self is allowed to be. After a while, there’s no need for the figure of the coach or the cop to mark the boundaries—you become your own enforcer. Don’t cry. Don’t talk back. Make the right jokes. On either side of that narrow plank, shame and punishment await.

Even amid the minefield of men’s sports, joy persists. Gay recalls how they shaved their legs together before games, feeling each other’s freshly smooth skin, and a teammate breaking his fall with a hand on his lower back. “In almost every instance of our lives—our social lives—we are, if we pay attention, in the midst of an almost constant, if subtle, caretaking,” Gay writes in his previous collection A Book of Delights.

Lest you think Gay just has a natural proclivity for happiness, he describes a significant period of doubt and depression following his graduation. “Falling Apart: The 13th Incitement,” catalogs how his pattern of repressing tough emotions—those things we think of as “not-joy”—led to a dark period of numbness, doubt, and depression.

“The obsessive thoughts were the churning, disturbed waters of grief denied, or grief refused, and the way to soothe those waters, it seems so obvious from here, is to wade into them. Into the deep waters, as my nana says.”

In the midst of his struggles, Gay attends a meditation class and is horrified by the teacher’s inquiries into a student’s discomfort. “Not only couldn’t I look at them talking about sorrow,” he says, “I thought it was cruel and unusual that we might be invited to watch.” Unsurprisingly, he later realizes, when you avoid your own pain, you can’t bear to look at anyone else’s either. If we want to be in meaningful relationships with others, we don’t just have a responsibility to ourselves to wade into the deep waters; we have a responsibility to our community. And holding each other while we fall apart, Gay says, is another word for joy.

Gay’s sometimes cheeky, always honest narratives are a pleasure to read, but the book’s real gift is that it prompts us to consider our own joy. What are my incitements? What family legends and ordinary delights and old, not-forgotten wounds would end up in my own tome of joy? Not the well-polished milestones, but the moments that feel like a handful of soil in my fist: fragrant, full of life and decay, and proof of how we sustain each other.

Koichiko

Koichiko