Best of the Haiku Challenge (June 2023)

Announcing the winning poems from Tricycle’s monthly challenge The post Best of the Haiku Challenge (June 2023) appeared first on Tricycle: The Buddhist Review.

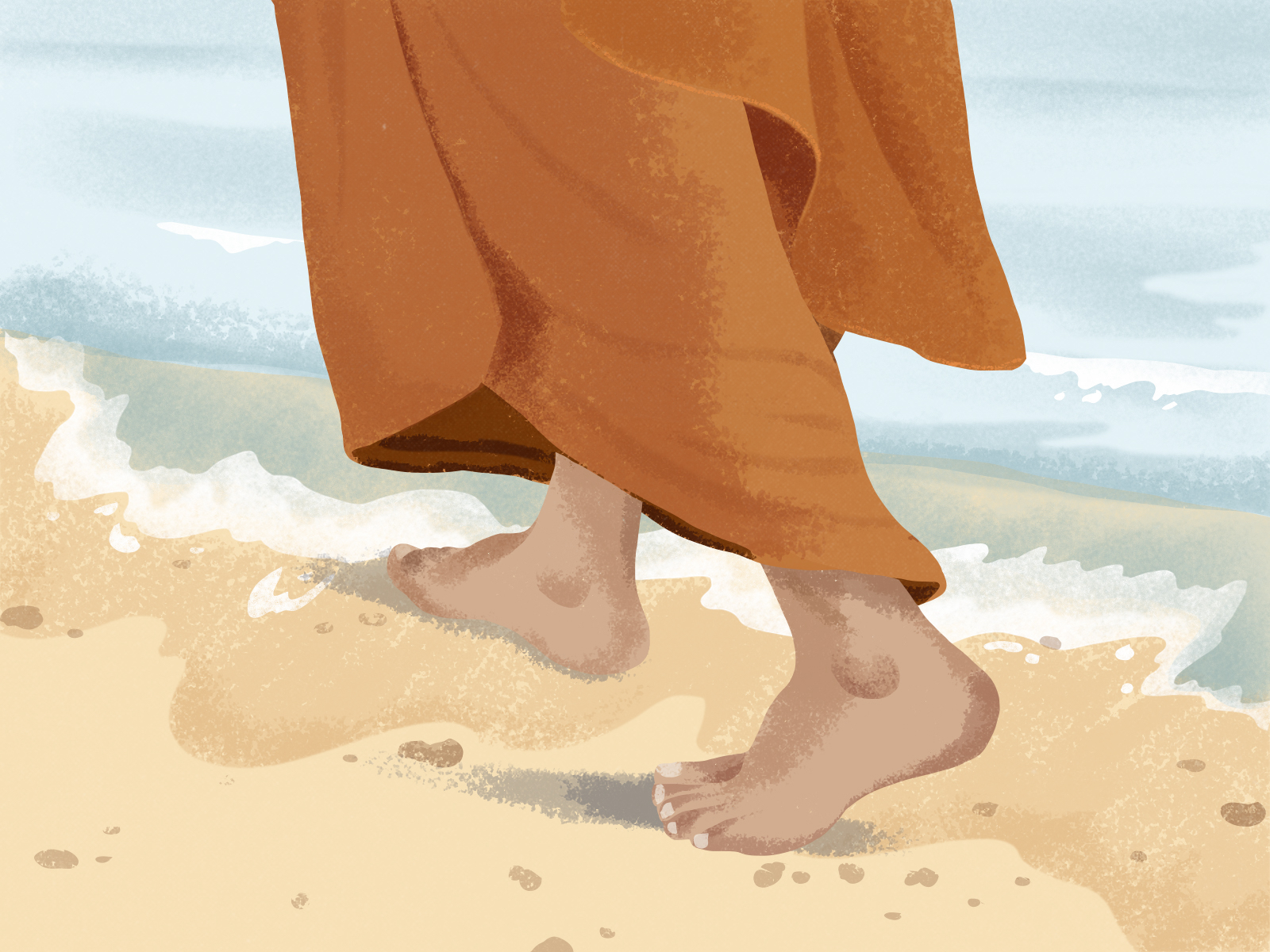

To go barefoot is to return to our original nature. That is why divine incarnations like Buddha or the Virgin Mary are nearly always depicted without shoes. Through bare feet we draw wisdom, vitality, and spiritual sustenance from below, like the tree that can reach to the heavens because its roots are anchored in the soil. Each of the winning and honorable mention poems for last month’s challenge found unexpected depth in this simplest, most primal of gestures: removing our shoes to experience our sacred connection with the earth.

Jackie Chou uses a surprising juxtaposition to state the core truth of Mahayana Buddhism: that samsara and nirvana are one. Thomas McCrossan discovers the rhythm of life itself in his sandy footprints filling up with sea water only to wash away. Marcia Burton experiences a sudden intimacy when she accidentally brushes elbows with her barefoot companion.Congratulations to all! To read additional poems of merit from recent months, visit our Tricycle Haiku Challenge group on Facebook.

You can submit a haiku for the July challenge here.

***

WINNER:

barefoot on the sand

pain from the splinter lingers

after it’s been pulled

— Jackie Chou

Haiku is the art of juxtaposition—the placing of two images side by side so that they inform one another in a surprising way. There are other techniques for producing what Bashō called “surplus meaning,” but juxtaposition is the most common. A good haiku pairs two elements that, taken together, add up to more than the sum of their parts.

On a trip to the shore, the poet has put the endless details and demands of daily living behind her to take a barefoot stroll on the sand. To go barefoot at the beach is to come back to our most primal connection. To meet life on its simplest terms.

The relief in such moments is palpable. The white noise from the surf washes over us as our minds relax into the rhythm of walking. We begin to think with our feet. To introduce the lingering pain from a splinter into such an idyllic scene feels intrusive at first—until we realize that the poet has said something profound.

In his Winter 2020 article for Tricycle, “What’s in a Word? Dukkha,” Andrew Olendzki explains that the First Noble Truth of Buddhism (usually translated as “Life is suffering”) doesn’t mean what most people think:

This central term [dukkha: “suffering”] is best understood alongside the related word sukha. The prefix su- generally means “good, easy, and conducive to well-being,” and the prefix du- correspondingly means “bad, difficult, and inclining toward illness or harm.” On the most basic level, then, sukha means pleasant while dukkha means unpleasant.

Dukkha is much lighter in concept than suffering, which is derived from the Latin “to hold up under.” In Buddhism, one doesn’t hold up under suffering so much as one wanders through it. That samsaric wandering is the subject of the poem.

On her way to the beach, the poet slips off her sandals . . . and immediately gets a splinter. This is how civilization works: it reduces the abrasions of life, but it can’t eliminate them. Beneath our clothes, inside of our shoes, we are all naked. Take away those protections, if for only a moment, and we are facing the pointy end of some stick.

The poet stops to remove the splinter, then continues on to the shoreline. The wound stings because of the saltwater, but the surf is the best thing for it. The water that causes her pain is also the cure for it.

The juxtaposition has too many layers to touch on all of them here. There is the movement from pleasure to pain/pain to pleasure that inspired early Buddhists to compare samsara to an ocean with rising and falling waves. And there is the splinter itself: a symbol in miniature for sickness, old age, and death. Not an accident so much as a simple fact of life.

Below these is a final layer which expresses the essence of the poem. Mahayana Buddhism ultimately teaches that samsara and nirvana are one. There is no escape from this world because there doesn’t need to be an escape. “This very place is the Lotus Land of Purity,” says the Zen master Hakuin. “This very body is the body of the Buddha.”

That the poet has managed to say all of this with a splinter is the “haiku humor” of the poem. The tone is detached, but not indifferent. Somewhere behind the words themselves is the lightest trace of a smile.

HONORABLE MENTIONS:

this constant heartbeat

barefoot thumps left in sand

fill up wash away

— Thomas McCrossan

accidentally

we brush each other’s elbows

barefoot at the lake

— Marcia Burton

♦

You can find more on June’s season word, as well as relevant haiku tips, in last month’s challenge below:

Summer season word: “barefoot”

when we step outside

we call it going barefoot

though nothing has changed

Submit as many haiku as you wish that include the summer season word “barefoot.” Your poems must be written in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables, respectively, and should focus on a single moment of time happening now.

Be straightforward in your description and try to limit your subject matter. Haiku are nearly always better when they don’t have too many ideas or images. So make your focus the season word and try to stay close to that.

REMEMBER: To qualify for the challenge, your haiku must be written in 5-7-5 syllables and include the word “barefoot.”

Haiku Tip: Get Yourself Free!

In Haiku World: An International Poetry Almanac, William J. Higginson devotes only one sentence to the season word barefoot: “What better symbol of summer than feet’s freedom from shoes and socks?”

At first glance, that might seem enough. In climates where shoes and socks are necessary much of the year, the summer weather can bring a feeling of liberation. But season words are complex entities with long histories.

The English travel writer Bruce Chatwin explored the design and function of the human foot in his book The Songlines. Our ancestors were made for yearly migrations, Chatwin concluded—journeys made barefoot because bare feet were evolutionarily designed for them over millions and millions of years.

For modern people, the feeling of ease that comes from going barefoot in summer is, therefore, more than freedom of not having to wear socks and shoes. Is it not, in some sense, also the freedom of returning to our evolutionary roots?

In The Vegetable Root Discourse, the recorded sayings of the 16th-century Chinese sage Hong Zicheng, we find the marriage of Higginson’s and Chatwin’s point of view:

When in the mood, I take off my shoes and walk barefooted through the sweet-smelling grasses of the fields, wild birds without fear accompanying me. My heart at one with nature, I loosen my shirt as I sit absorbed beneath falling petals, while the clouds silently enfold me as if wishing to keep me there.

As a season word, “barefoot” belongs to the human affairs category, which includes summer clothing, customs, holidays, sports, and so forth. As an experience, however, going barefoot calls much older memories to mind. Our feet remember a time when there was no indoors or outdoors—although, granted, there may not have been a word for it then. Who needs a concept like barefoot when there is no such thing as a shoe?

ValVades

ValVades